My world has had some lows lately. Causes I care about, institutions I respect, and people I admire, all fighting, and in many cases losing, in ways that have felt at times cataclysmic.

It's times like these I am grateful to be a student of history:

I remember listening to an eminent historian of Germany once talk about that country and how the entire narrative arc of the nation changed depending on when you began and ended its story.

Start with the Holy Roman Empire and end in 1871 with German Reunification?

Triumph.

Begin at Weimar and end in 1945?

Tragedy.

Now, let's be clear: this contextual view of history doesn't decrease its meaningfulness or utility.

History is, simply put, the ongoing act of (re)examining the past. We will always bring the baggage of the present to that analysis, but if we are clever and humble enough to bring a diversity of perspectives, we will have a richer understanding of what and those who came before us – and what we might learn from them.

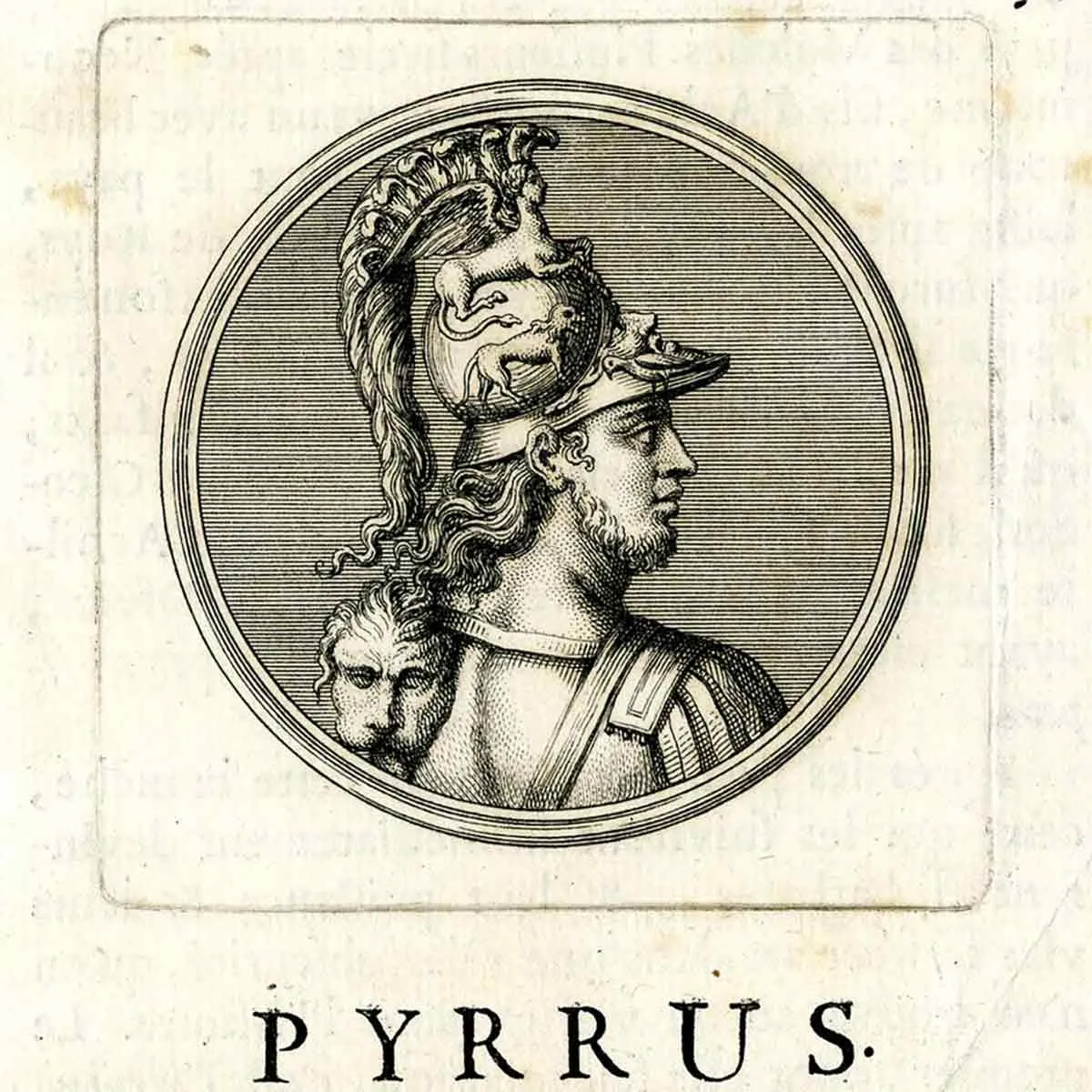

When I think about these losses I witnessed of late, I think about one of the most familiar, deeply rooted – and often misinterpreted – parables of failure from Western history: the story of Pyrrhus of Epirus.

You may never have heard his name before, but you may have heard something similar in that hard-to-pronounce phrase meaning something like "a victory that wasn't worth it."

A Pyrrhic Victory.

His Roman Empire

Pryyhus was the heir to a dynasty of tribal Greek-speaking peoples, the Molossians, who effectively represented the non-city-state periphery of the Hellenic world: Epirus.

The Molossians' main claim to fame came through a princess named Olympias, who would marry Phillip II of Macedon. Her son would be Alexander III – or, as we know him today, Alexander the Great.

Molossians would participate both in the expansion of the Alexandrian project across the Eurasian landmass, as well as its dissolution. They would form part of the Diadochi, the "recievers" of the wealth that their great leader had bestowed upon them, and which they would now divide amongst themselves.

Pyrrhus was born into this chaotic world and, despite his familial lineage and linkages to Macedonian power, would ascend to the throne at 13 only to be quickly removed a year later. Cassander, one of the main rivals in his early life, was one of these Diadochi who warred for Alexander's legacy, first, in a sense, by having his original heir murdered.

After living as a hostage of Ptolomy I Soter in Egypt for a few years, he would win over the old general of Alexander and get the money and resources he needed to actually retake his throne.

A decade and a half later, Pyrrhus would fight one of the most significant wars of the ancient world at that time, squaring off against the Romans and repeatedly besting them in battle. The conflict, the Pyrrhic War, ultimately pitted the empire-building tendencies of Pyrrhus against those of the upstart Roman Republic, which, having recently subdued the Samnites, was now turning hungry eyes to the sprinkling of Greek-speaking "Magna Graceia" colonies on the southern peninsula.

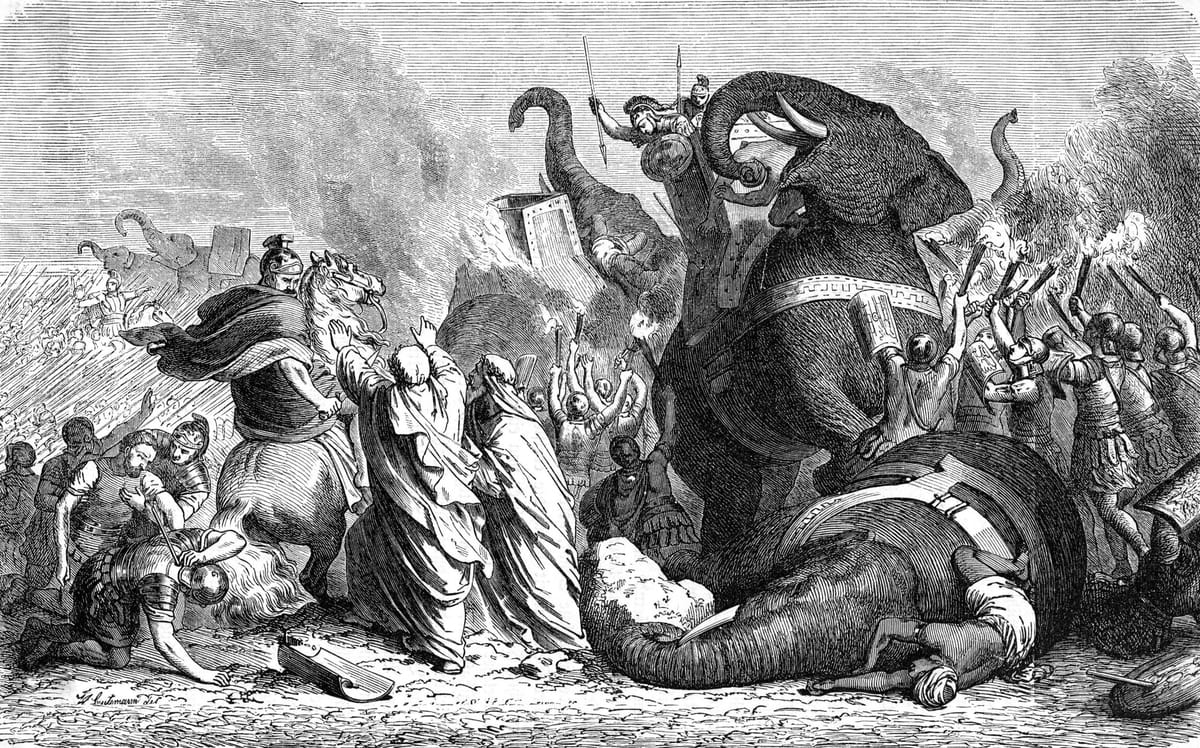

What we know as the first true 'Pyrrhic victory' came at the Battle of Asculum, the second major conflict of the war.

While his war elephants had been a decisive factor in their first engagement, this time around, the Romans cleverly manoeuvred over the terrain to deny Pyrrhus the ability to use them and devised a series of traps to take the animals down. This is all the more impressive considering this was only the second time they had seen animals that were as no doubt as frightening and otherworldly to the Romans as the Mûmakil were to the Rohirrim.

Despite their best efforts and clever tactics, the Epirotes would win the day – but at a cost. Ancient estimates vary greatly, but Pyrrhus may have lost as much as 10% of his total fighting force and a significant number of his most experienced commanders and elite hoplites. It was these losses that supposedly caused him to have exclaimed:

If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined

Going for Broke

Asculum wasn't the last battle of the war for Pyrrhus – far from it. There were more Greek-speaking city-states in Sicily, and at the request of Syracuse, the Epiriot king would move over onto the island and unsuccessfully fight the Carthagians for a while. Despite once again some limited successes, his attempts to cement his control were not viewed favourably by the locals. Eventually, facing defections and reinforcements from Carthage, he decided to decamp to his Peninsular holdings, where the Romans were still pushing aggressively.

He fought the Romans up the peninsula again and suffered a defeat at Beneventum in 275 BCE, leaving this the high-water mark of his campaigns against the republic. He would fight his way back to Epirus and, after a successful campaign that briefly led him to being crowned king of the Macedons, he would be killed after his final, unsuccessful battle in Sparta.

The Lessons of Pyrrhus

The Pyrrhic War has been a near-limitless source of parables and 10-cent wisdom almost since the day it ended. Most often, the story is about the simple parable of trying not to confuse tactics for strategy – "win the battle, lose the war."

There is a wisdom to this: regardless of the relative cost of each battle he fought, Pyrrhus' approach was essentially freewheeling. He seems to have played whatever hand he was dealt almost immediately, jumping from campaign to campaign and war to war almost without pause for the entirety of his adult life until his death.

While both his friends and enemies would celebrate him as an accomplished tactician and brilliant battlefield leader, he was considerably less skilled in the world of politics. The Military Engineer writes of him:

he ruled in a despotic way and the conquered cities rose against him whenever there was hope of successful resistance. His victories on the battlefields were simply military successes; he established nothing of permanence; he did nothing to better the condition of his own people or the people of the lands he occupied; he was merely a despot governing to suit his own whims and fancies.

To transmute this from the military to the political, we often say: there's campaigning, and then there's governing.

It can be frightening, honestly, to see how few people in electoral politics seem to understand this difference. You can run a government by press release, but if you have even a vague intention to better the lot of the people you're responsible for, this strategy is (a) time-limited and/or (b) self-defeating.

It takes hard work and, in Joseph Heath's wonderful framing (with thanks to Pink Floyd), "eating your pudding before your meat," to make effective, lasting change.

Niskanen Center - Improving Policy, Advancing ModerationBrink Lindsey

Niskanen Center - Improving Policy, Advancing ModerationBrink Lindsey

But beyond a basic "focus on the fundamentals" message, I think Pyrrhus also has an interesting, higher-level insight: powerful, motivating stories don't only have to be about winning.

I Lose, I win

Contemporary historians have debated the veracity of the entirety of the story of Pyrrhus for some time now. He's absolutely a real historical figure, but the mythology of him as the big bad of the Roman power and the only one who ever "got close" to ending their republic proved useful to generations of its empire-builders.

If you take a middle-of-the-road approach to the historical records of the campaign, you could simply sum the Pyrrhic war up as: a series of largely inconclusive battles fought between the early Republic and a minor Greek-ish warlord. Pyrrhus' marginal advantages in equipment and matériel allowed him to eke a few victories out before he finally turned tail and went back where he came from.

But that's not the story the Romans (or the Greeks) tell. The war that the Epirotes fought was nearly existential (for the Romans) and noble (for the Greeks); it involved cataclysmic battles with massive numbers of troops (according to both). It was useful (mostly to the Romans) to inflate the whole conflict in retrospect.

For anyone looking to proactively shape history, the question of how to tell your story must apply not only to wins but also to losses.

Generations of Romans turned Pyrrhus into a mythical foe – a 'big bad' who was one of precious few who had come close to challenging their dominance. This could be both a source of confidence – we beat him – but also of humility. Leaders and the public who understood the parable could be vigilant and resourceful in the face of other, inevitably lesser, challengers.

Perhaps most importantly, to those who are not within the halls of power, I think Pyrhhus' story also shows how what it means to win is profoundly shaped by the timescale you view history on.

From the foundations laid by Alexander the Great, Pyrrhus was able to briefly cobble together meaningful power in the centre of the Mediterranean world – one even to briefly challenge Rome – but it was not to last. Indeed, of all of Alexander's generals, it was only Ptolemy in Egypt who would develop any lasting historical resonance. Indeed, despite his success and longevity, what he built would also be laid bare by Rome eventually. And of course they, eventually, by others.

Another parable, this one from the Huainanzi (淮南子) in China, epitomises this best. In it, the "old man who lost his horse" responds to each loss he suffers by wondering if it won't bring him good luck, and each seeming success by querying the opposite.

History is indeterminate; never finished. One brutalising loss may in a generation be the catalytic force that prompts renaissance-inducing transformation, depending on your perspective.

Maybe this is too pithy, but as someone committed to a world that is to me more humane and plentiful for all, to me it can be even simpler: the events of the day are what we make of them.

Go forth.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.