We all watched it, as far as I can tell.

If we were sneaking a glance at our phones while at the checkout counter, or found that perfect angle where our phones could rest off-screen during a Zoom call, or maybe we just told the kids to be quiet for a second “so we could see what was happening,” I think everyone I know had at least a few moments of focus to take in a day that will go down in history. We watched as a gang of angry, white men marched into the United States Capitol Building and pilloried it; leaving dangerous explosives, stealing civic property, and killing several people.

If I am honest, though, what really shook me wasn’t watching these insurrectionists, white nationalists, and domestic terrorists practically waltz into what, until the day prior, I had assumed would be one of the most well-protected buildings in the world.

What got to me was watching all— and I mean all — of them walk out.

Congresswomen and men have since indicated that those who participated in the insurrection will be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. The vast and powerful surveillance state that has grown since 9/11 will be mobilized to bring to justice those who would profane the halls of a site of a nation that has consistently referred to its democratic traditions as a ‘beacon on a hill.’ And yet, all of that power, which will no doubt catch, try, imprison, and otherwise punish many of those who undertook these deeds, will have failed before it even begins. It will fail because the entire world watched not only an aggressive yet disorganized mob of fascist LARPers break into the centre of government that this entire apparatus was in theory created to protect, but that they got out after they did it.

The American Republic was, in that moment, forever tarnished and likely irreparably so, because of the story that can now be told about that ease with which insurrectionists can attack its government and get away with it.

One of the more difficult, but perhaps more useful things that I learned in studying history is that it’s always changing. Not in some literal sense that the past is always being materially altered — time travellers mucking up timelines and all that — but that our understanding of history, and, most importantly, how we react to it or ‘learn’ from it, are changing. In the dusty academic terminology, we can say that it is hyperstitional, that is, something that gradually becomes real through a process of repeatedly being discussed, believed, perceived. The more we believe something, in certain senses, the truer it becomes — a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy.

Benedict Anderson, great theorist of nationalism, is perhaps one of the best examples of this thinking in his work on “imagined communities.” Nations, he argued, are not natural. He argued that they require deliberate effort on the part of different actors — from politicians, to artists and academics, to everyday people — to construct (i.e., imagine) a series of commonalities and shared experiences across a group of people. Nations require a series of symbolic (flags, coats of arms) and material (constitutions, border crossing, military hardware) signs and systems to be put in place both mentally and physically in order to exist. The more these are invested in and the more they are reinforced by the public of the nation itself, the stronger they can become. This relationship between these instances and flows of investment (mental, physical, monetary, cultural) and the ‘realness’ of the thing itself is critical. It is not the case that a nation is fake, or somehow made-up —Anderson and fellow-travellers like Edward Said argue that these imagined communities (or ‘geographies’, in Said) are not primordially natural, but they are real — deliberate, but real. And the more we perceive them to be real, the realer they can become.

The same phenomenon can be observed at numerous scales — nations, political ideologies, all the way down to sports teams. Cycles of creation, sharing, formalization and realization, and, if they are successful enough, reinvention and reimagination. A non-linear process with no definitive end, only dynamic movement over time.

Like a great heroic epic of the Kwakwakaʼwakw or the Athenians, a story told again and again with flourishes and contestations subsumed or forgotten over time.

What does any of this have to do with a group of thugs trying to break into the centre of American democracy?

Esoteric as all of this might sound, I draw two insights relevant for us today from this particular conception historical memory:

- The events of January 6th are going to be purposefully and subconsciously shaped by a variety of Trump-allied forces and (re)written in such a way as to show that the entire event was a win for the first movement. The fewer the consequences to their members, the truer this story will feel, for MAGA-types and, crucially, the general public alike;

- In the absence of any clear consequences, the narrative of an insurrectional success (even with Trump seemingly set to relinquish power) or, worryingly, that they almost succeeded, will embolden others to try again.

The first point feels broadly self-explanatory in the age of “fake news,” parallel media ecosystems, social media manipulation, and as David Roberts wrote so poignantly several years ago, “tribal epistemologies.” But the second point one feels incredibly important to consider and, I fear, respond to. Sadly, I believe, it has a historical precedent that should chill us to our very core:

The 1923 “Beer Hall Putsch” in Munich, Germany.

The Deadly Meeting of Fantasy and Bitterness

Germany, 1923. The wounds of the First World War are healing, in fits and starts, but with some current of hope. Germany is still reeling from economic shocks as it struggles under the combined weight of the immense reparations it owes Great Britain and France, as well as its own internal challenges around the rebuilding process and economic shifts post-war. Culturally, too, this era was awash in incredible change that raised the ire of conservative forces across the country. Reactionaries decried the state of degeneracy they felt their pure, proud nation was falling into — homosexuality, socialism, and otherwise.

Amidst all of this, a failed Austrian painter, Adolf Hitler, had become deeply involved with the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (“NSDAP,” Anglicised to “Nazi Party”). After climbing the ranks of the party, an embittered war veteran and believer that Germany had been “stabbed in the back” by Jews, communists, republicans, by 1923, Hitler and many of his supporters believed that now was the time for conservative forces in Germany to strike. As we know it today, they wanted to ‘make their country great again.’

The Nazi Party, buoyed by growing numbers and an upwell of support for its relatively new leader, Hitler, attempted a coup d’etat in Munich, Bavaria over two days in early November, 1923. Approximately two thousand armed former soldiers and thugs marched on the city centre, but were stopped by police. Sixteen Nazis and four police officers were killed in the ensuing violence. Hitler initially escaped, but was later found and tried for treason.

As Wikipedia summarizes nicely:

The putsch brought Hitler to the attention of the German nation for the first time and generated front-page headlines in newspapers around the world. His arrest was followed by a 24-day trial, which was widely publicised and gave him a platform to express his nationalist sentiments to the nation. Hitler was found guilty of treason and sentenced to five years in Landsberg Prison, where he dictated Mein Kampf to fellow prisoners Emil Maurice and Rudolf Hess. On 20 December 1924, having served only nine months, Hitler was released.Once released, Hitler redirected his focus towards obtaining power through legal means rather than by revolution or force, and accordingly changed his tactics, further developing Nazi propaganda.

Put even more simply: after the failed insurrection, its publicly identified and indicted leader, Adolf Hitler, received a slap on the wrist sentence that in fact gave him even more opportunities to spread his ideas and build his power.

When Mistakes Become Successes

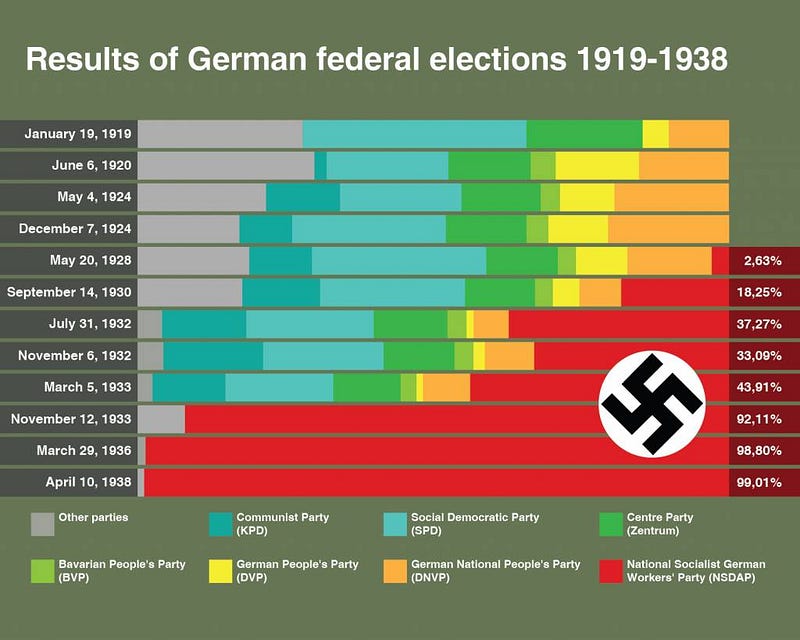

A decade after the failure of the ‘Beer Hall Putsch,’ Adolf Hitler, the often derided former enlisted man and a man alternately ignored or feared by forces across the German ideological spectrum, was Chancellor of Germany. While his initial attempt to seize power had failed, his ruminations during the writing of Mein Kampf and his later experiences in vastly expanding the capacities of the Nazi Party, helped inspire another generation of fascist organizations around the world, as Hitler had been inspired by Benito Mussolini in Italy, and his infamous “March on Rome” that had won him government in the first place.

Reactionaries and fascists around the world would look to both the electoral and paramilitary power of the Nazi Party as something to be emulated, especially after Hitler became Chancellor in 1933. To us in 2020, this progression feels sadly natural, nigh inevitable. The putsch was simply a milestone on his eventual rise to power — one that others, for example, the MP-turned-fascist rabble rouser, Oswald Mosley, who was similarly inspired by Hitler to attempt an authoritarian coup in the United Kingdom.

But there was nothing natural or inevitable about Hitler’s rise to power after his failed uprising. The Nazi Party grew in strength in the mid 1920s, but as prosperity in Germany grew towards the end of the decade, the currency having stabilized and sectarian violence declined dramatically, they were not in no position to take power until after the global economy collapsed in 1929.

Even after the economy collapsed and Germany entered the phase of hyperinflation we all know so well, even still Nazi ascent was not guaranteed. The electoral bargaining that took place in 1933 was intense, and the thinking on the part of the aristocrats and business conservatives who tried to ‘ride the tiger’ with the Nazis was that Hitler and his ilk could be controlled by the ‘serious people’ who had, up until very recently, been Germany’s enduring ruling classes.

Their arrogance and need to maintain power in the face of the very real threat of Nazism will forever be a stain on the history of Germany and the world.

Defeating Fascists

It is trite to say that we if “learn from Germany’s mistakes” American can defeat the anti-democratic, authoritarian forces that are looking to take over the country (or, indeed, any of their allied forces all over the world). The contexts are vastly different. As the old saying goes, though, history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.

Thinking about strategies and tactics that might have halted, or at least handicapped, the Nazis, and the context we operate within today, there are three broad areas of work I think those fighting against fascism must work within. These strategies are broadly emergency, institutional, and narrative.

What will tie them all together, and indeed, likely determine the success of Americans in staving off another such insurrection is consequences. Hitler never really suffered for his authoritarian attempt to seize power in 1923, and part of that was his ability, especially post-trial, to control the narrative of the putsch and everything that came after. In our world, these same stories are already shared within gated digital communities like the failed Parler, or simply via private messaging and offline, and on more run-of-the-mill insular groups inside public social media platforms like Reddit, Twitter, and Facebook. Whether these conduits of information and echo chambers retain their strength will be one of the major determining factors of whether anti-democratic organising can be addressed or not.

Part of what enabled me to write what follows is not to say these are definitive actions, but more thematic areas of work

The emergency work in some ways is the easiest to undertake. This work includes practical, immediate things, such as investigations into the failures of the US Capitol police, that must be taken to understand where threats to US democracy may lay. But it can also include symbolic steps, such as censure, and though less likely, the impeachment or recalling of figures, including the President of the United States himself. The key of any of these steps is to an unavoidable and overwhelming sense of consequence for anyone who participated in or assisted the insurrection. The perfect example is US gold medal Olympian, Klete Keller. The United States Olympic Committee and other, relevant sporting bodies should immediately confiscate all of his medals and send directives to all of his sponsors to cancel any association with him for clear participation in seditious and treasonous action against the people of the United States.

Legislatively speaking things will be more difficult, but will be part of the larger democratic ‘fire wall’ against these kinds of future events. Again, censure and, where possible, charges, against elected leaders who participated (as some state and municipal legislators did) or otherwise contributed to the events must be undertaken. In the early days of the Biden administration and more systemic challenges must also be tackled, though sadly progress will be tenuous and time-consuming, such as aiming to more effectively balance the electoral college by granting statehood to Puerto Rico and Washington D.C.. Eliminating the Electoral College should remain a long-term goal of any small-d democrat in the United States, though, sadly seems an unlikely opportunity for the foreseeable future. With that said, the district and local-level work to break through gerrymandering, register voters (particularly people of colour), and overcome other impediments to democracy will be absolutely critical. It is difficult to overstate the service that Stacey Abrams has done not just for Democrats, but for American democracy, with her work in Georgia. Investing in this basic work at the local level must continue to be one of the central planks of anti-authoritarian organizing for the foreseeable future.

Most difficulty, but in many ways most critically, the forces of democracy must be unimpeachably and incontrovertibly clear in how they tell the story of these events — what happened on January 6th was sedition, insurrection, terrorism, and treason. It was not ‘economic anxiety,’ nor was it a reasonable attempt to question so-called election irregularities. Any of the nuanced, sociological views on why people have or did vote for Trump have no place in the telling of what transpired on January 6th. From the view of a Canadian, American patriotism is one of the most powerful forces on earth — it should be marshalled here to bring justice to those who have so egregiously attacked the best values of this complex nation.

The Power of Stories

Maybe it’s my personality, perhaps it’s growing up in a country whose motto is “peace, order and good government” and not “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” but the starkness of this story is a difficult one to tell. The idea that myself and others would compare what happened in Washington D.C. to events in Germany and elsewhere that have, collectively, resulted in indescribable and uncountable human misery and death is and should be arresting. And yet, even amidst my relative safety as a comfortable, middle class, white man, I feel compelled to raise the alarm for people of my same, comfortable status — as Black folks and people of colour have said since the end of the US Civil War, racism and anti-democratic inclinations will not be swept away with kind words. They required a deliberate program of imagination to be created, and that and much more will be required to excise them.

What is most important to me in writing this, though I doubt it will reach very far, is that we must take what happened in the United States seriously. Ruptural moments in politics matter profoundly. Many leftists look at the events of May, 1968 as one of, if not the, the death-knells of a vibrant, utopian alternative to capitalism. In the United States, the rejection in 1987 of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court convinced conservatives that every appointment must be an existential battle for control of the institution. These stories and innumerable others have had a profound impact and have guided the course of political movements based on their understanding of the success, failure, possibility, and threat of the moments they inhabited.

I worry deeply and profoundly that a story of “we got what we came for,” or, “we came so close,” will be the lesson that white supremacists and anti-democratic extremists will learn from the events of January 6th. We must defeat these stories at all costs on all fronts. The stakes could not be higher.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.