When I started this newsletter in October of 2024, it was an unabashed experiment. I had become inspired by those, such as Maggie Appleton and Andy Matuschak, who tended "digital gardens" – spaces where they kept a living and sovereign archive of their ideas and feelings in various states of development – and wanted to build the same for myself.

Over a year, it feels more important than ever both to have a space of my own to write and, crucially, to use it.

But with a few blogging callouses on my hands and the chance to reflect with others working in the world of ideas – like my far more diligent and organised friends Uytae Lee and Jen Abrahams – it's clear to me that there's still considerable room for improvement.

To that end, I've created a survey that I'd greatly value your input on. If you just do the multiple-choice questions, it shouldn't take you more than a minute, but written responses are also greatly appreciated.

My central aim is to make my content a little more predictable and legible for my audience, as well as to create some smoothness for me in how I deliver it. In some ways, this picks up on an idea I had in 2023 about the use of apostilles as a writing device – I may yet pick that back up again, but I want that to be something I do in dialogue with my audience.

George Patrick Richard BensonGeorge Patrick Richard Benson

George Patrick Richard BensonGeorge Patrick Richard Benson

A Look Ahead

I spent time over Christmas and New Year's thinking about what I wanted to talk about here in the coming months. While I have a flurry of article ideas, I wanted to sit a level higher and talk about the themes and ideas that I think are at the core of what many of us are grappling with these days and which I intend to delve into over the next year, and likely beyond.

Attention and Focus

We've been stuck in a conversation around focus and attention for some time now. We've rapidly progressed from cottage industry to a full-scale lost-attention-industrial complex, complete with an ecosystem of apps, books, and, now, with Australia's youth social media law passed last year, finally policy.

It's pretty much dépassé to complain about technology companies stealing our attention. From Jenny Odell's How to Do Nothing in 2019 to Johann Hari's Stolen Focus in 2023 to Chris Hayes' The Siren's Call at the beginning of 2025, we're amidst an ever-darkening conversation about how little attention we all have – and how it's being taken from us by major corporations.

While there are some good arguments and historical context within the discourse, much of this discussion enters the realm of moral panic pretty quickly, and is also (I think by design) largely focused on how we protect our individual attention. However, as I watch governments around the world struggle to look beyond the next week, I contend that attentional breakdown is not just individual, but institutional.

The inability of institutions to sensemake amidst this profound period of disruption across every dimension of our society – ecology, technology, economy, culture – fits nicely into what Daniel Schmachtenberger has called the metacrisis: an interconnected crisis not only of environmental degradation and economic inequality, but one of meaning-making itself. With a breakdown into "tribal epistemologies," the ability of complex societies to make meaningful decisions will break down, leaving them vulnerable to the predations of actors with coherent, and often malicious, worldviews.

State Capacity

If attention is how we apprehend the world around us and decide where we want to go in it, capacity is how (and how close to) we get there. Those who talk to me regularly know that I have become quite obsessed with this concept, drawing inspiration from the work of the Niskanen Centre.

Niskanen CenterStudies State Capacity A state capacity agenda for 2025 December 20, 2024 • Jennifer Pahlka, Andrew Greenway Read More

Niskanen CenterStudies State Capacity A state capacity agenda for 2025 December 20, 2024 • Jennifer Pahlka, Andrew Greenway Read More

What I find fascinating about this conversation about state capacity, specifically, is that some of the first people to raise this concept were libertarians who, coming out of the CATO Institute, recognised that even a small government needed to be able to do its job well. Following a similar journey, Canadian conservative thinker Sean Speer has similarly become animated by this cause.

On the other side of the spectrum, Jonathan Heath has brought progressives to task for what he calls a "all meat, no pudding" (with thanks to Pink Floyd) focus only on setting big objectives for government and not worrying sufficiently about its capacity to achieve them. The brilliant Anne White has an incredible project on this that I can't wait to see more of this year.

What's attractive and important about state capacity as a concept is that it is inclusive of big-picture concepts like the "defence industrial base," while also very much including the experience of individual citizens in how they interface with the everyday machinery of government services and functions. The ability of the government to deliver passports to those who want them is, in this view, just as important – and indicative of its efficacy – as its ability to manage a pandemic or fight a war.

As an international order based on norms recedes, perhaps for generations, the raw capacity of states to deliver on their objectives, big and small, will take on an increasingly existential character. History offers some lessons for those who rise to this occasion and those who don't.

Historical Rhythm

As far as I can tell, we've been here before. In some ways, the Progressive Era in the United States is a useful historical comparator to where many societies find themselves today, and indeed may serve as a generational echo for what comes after Donald Trump. Institutional scleroticism, political graft, massive economic inequality, and global geopolitical instability amidst the decline of a prior international order.

Sound familiar?

In the United States, it was Progressives – Liberals with an institution-building drive - who fought back and ended up building institutional architecture that Americans have enjoyed to this day, and which is now under assault. In Europe, it was the Christian and social democrats. Canada, perhaps unsurprisingly, was late to the party.

George Patrick Richard BensonGeorge Benson

George Patrick Richard BensonGeorge Benson

African and Asian decolonisation are different in many respects, but the concepts and strategies pursued as part of nation-building, I think, still hold relevance for anyone looking to navigate this age. Figures like Julius Nyerere and Lee Kuan Yew, in particular, interest me in how they pursued national unity within poor, complex, post-colonial societies during periods of extreme political instability.

My fundamental animation through this historical comparison is to understand the how of the builders – utopians and pragmatists alike – who saw a world on fire and didn't just throw water on it, but built firehalls.

Technology and Freedom

As much as there are echoes and rhythms to our moment with the past, the most obvious and divergent factor is technology. Whether the specific case of large language models (LLMs) challenging the very idea of independent human thought, or the rapid advance of new hard-tech forms, such as the "electro-tech stack," I believe we are simultaneously too deterministic and insufficiently causal (both up and downstream) in how we understand their implications.

The easiest example of this is artificial intelligence (AI). As John Lancaster wrote last year, we can think of the potential of AI – that is LLMs, the less-remembered machine learning (ML), and other applications such as in robotics – as arriving into one of four scenarios:

- "AI is a giant nothingburger." LLMs turn out to have "insuperable limitations" and are mostly given up on, people going back to what they were doing before. Exceptionally unlikely, but conceptually possible.

- "Someone builds a rogue superintelligence, which destroys humanity." This is the fear – or at least highlighted possibility – of people like Aric Floyd of 80,000 Hours and the new project AI in Context. It's not one I subscribe to directly, but I think there are ways in which AI enhances other geopolitical risk factors.

- AI leads to the singularity, and this unleashes an era of heretofore unimaginable human prosperity and super-abundance. Most of the big AI CEO's seem to think this is possible – but only if their particular model is the one that gets there first.

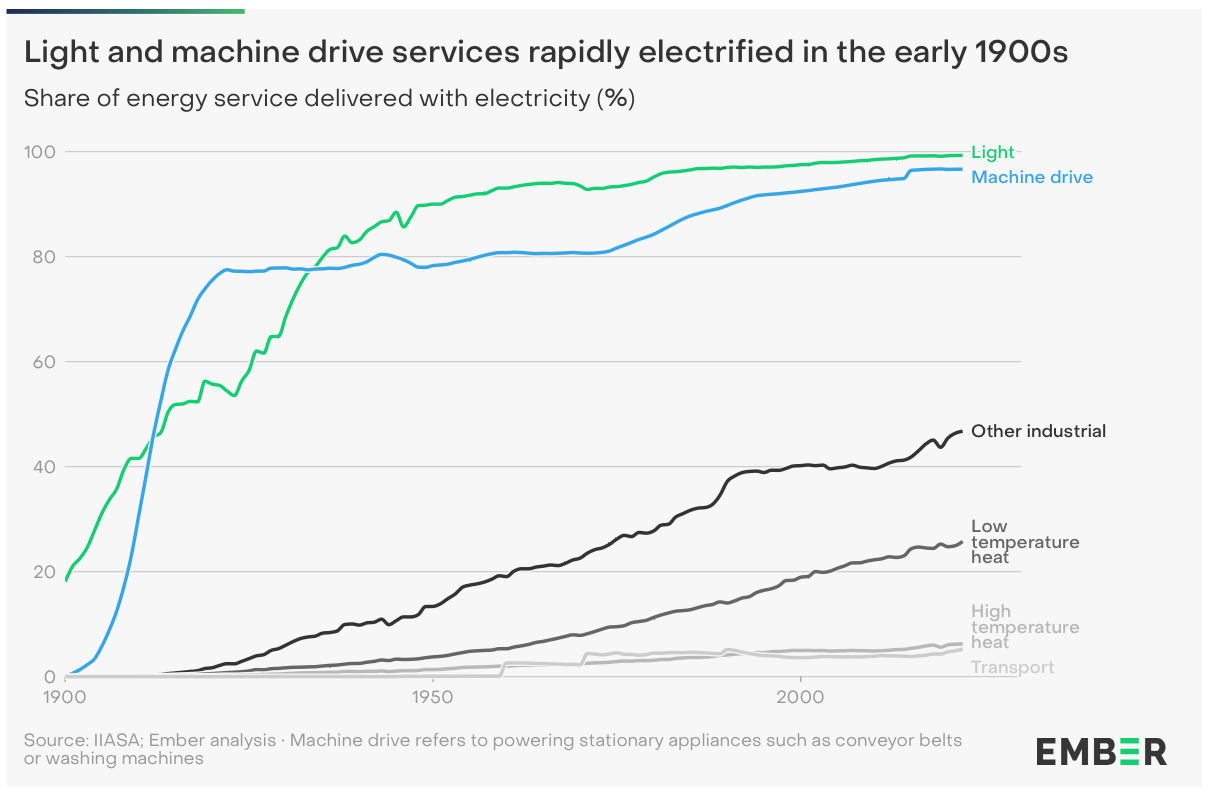

- AI is a "normal technology," as argued by Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor. In short, the family of technologies, but particularly LLMs, will follow all of the normal rules of technological uptake and diffusion and almost certainly have as great an impact as the rise of electricity and railroads, but not to the degree and certainly not with the speed of the second or third scenarios.

Though I often write about the positive implications of the transition from a fossil fuel-based to an electrically-powered future, I fundamentally view it in the same terms as Narayanan and Kapoor view AI (and on which I also agree). We are (still) in the middle of the "long march of electrification" that started in the 1900s and which is still filtering out over the whole of the global economy.

Understanding this kind of "normal technology" diffusion requires you to hold a few ideas simultaneously, together which break the frame of the entirely pessimistic or hyperbolic:

These technologies, as just two loose case studies, are remarkable, and indeed will be (over time) world-changing.

They are used by, and to varying degrees, for humans, and so follow all of the messy incongruities and inefficiencies of our cultural affect, irrational exuberance, and petty vanities.

The way that these technologies (and others) diffuse will amplify some existing power structures (e.g., return on capital) and break others (e.g., trade balances).

From all of this, we don't get a nothingburger, nor an instantaneous transformation of our civilisation, but the kind of transformation that is indeed profound and world-shifting, just mostly in retrospect.

This is all from a macro-view, however. As much as I am interested in the systemic, grand-historical transformations unfolding here, I am also equally interested in the potential for individual human flourishing. For LLMs, the results thus far are middling to very negative. But the promise of "digital twins" of the body, on the other hand, is a technological marvel that could transform medicine.

We have gotten used to thinking of how technology can free us from a instance of drudgery – waiting for a taxi, sending money to a friend – but I think we've lost site of the profoundness of its possibilities. Technology never guarantees freedom; but it can help deliver it if the operating environment is right. How we set that environment, and what is yet possible if we do, gives me hope and focuses my attention greatly these days.

Learning In Public

Within the idea of a digital garden is embedded that of "learning in public." It's an approach to doing the hard work of trying to understand something with the humility of showing your work along the way. I wanted to use this space to teach myself things I thought were important to know, and to share those learnings with others who I thought might also be interested.

Importantly, I have never hoped that this would be a one-way proposition.

As I experiment with this space more in 2026, I aim to find many more new and diverse ways to engage with you all here that are dynamic and interactive. I am working towards doing interviews over the course of the year, and I hope to also find ways to host group dialogues, like "fishbowls," as well. I welcome any and all suggestions and opportunities to collaborate in this (and any other) respect.

In closing, I want to return to the theme of attention.

We live in an age of incredible plentitude in writing and thought. Brilliant people share their ideas every day for free in ways that are accessible and dynamic. At the same time, our attention has never been more under assault, lured with decades of gambling industry dopamine hacking. That you choose to spend some of this precious resource with and on me is not something I take lightly.

Thank you.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.