A recent report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) has a earth-shattering conclusion:

Global oil demand will almost certainly peak by the end of this decade.

This is a claim that's been made more than a few times, but I found the resoluteness of it in the report this time was something I found halting.

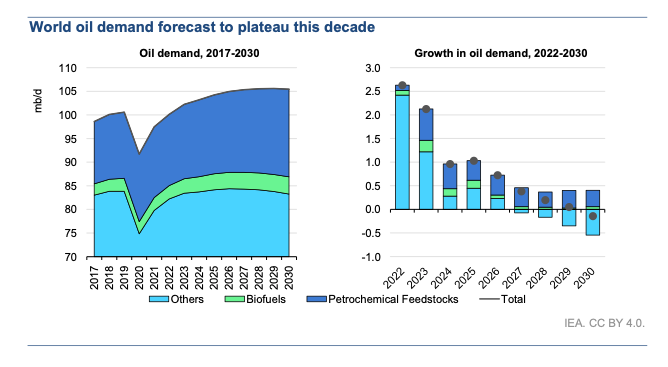

Based on their most recent analysis, demand will continue to grow with strong demand from fast-growing economies, particularly in Asia, but these will be "increasingly offset" by factors such as EVs, energy efficiency, and declining oil use in electricity.

Between now and 2030, global demand for oil, which also includes biofuels, will "level off" at near 106 million barrels per day, and begin to decline after that. Interestingly, most of this growth will be led by the use of petrochemicals and not by significant growth in combustion.

Importantly, this will also coincide with a global glut of production of nearly 114 million barrels per day by 2030, meaning we are now entering into a highly price-competitive global oil market.

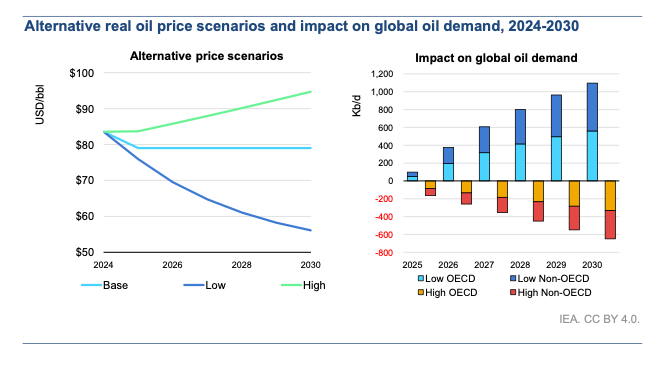

The IEA's modelling breaks pricing into three scenarios:

- A base case where "an average 2025 Brent crude price of about USD 79/bbl [...] is held constant in real terms over the remainder of the forecasting period [to 2030]."

- A high-price scenario, where "oil prices increase by 2.5% in real terms per annum, in line with their long-term historical pattern."

- And a low-price scenario here, "[e]stimates of future spot prices are based on the ICE Brent forward curve (slowing from USD 79/bbl in 2025 to USD 69/bbl in 2030). These prices are then discounted to real terms."

They note that there is a reciprocal relationship between these price dynamics and overall production: lower prices will likely curtail further production unless, like the Saudis often do, people are willing to stick out troughs in prices by subsidising - either through debt, foregone revenue, or otherwise - the costs of production. And as they estimate, the potential decrease in prices in the low-cost scenario is quite dramatic.

The Relevance to Canadians

As a Canadian, this information feels especially relevant. As just one example, it was reported earlier this year that Alberta's provincial budget was on the "knife's edge" of a deficit when oil fell to $72 a barrel.

Back in 2021, Alberta was running a $16.9 billion deficit at around $60 a barrel. So, every penny of movement, one way or the other, is profoundly important for both Albertan, and Canadian, finances.

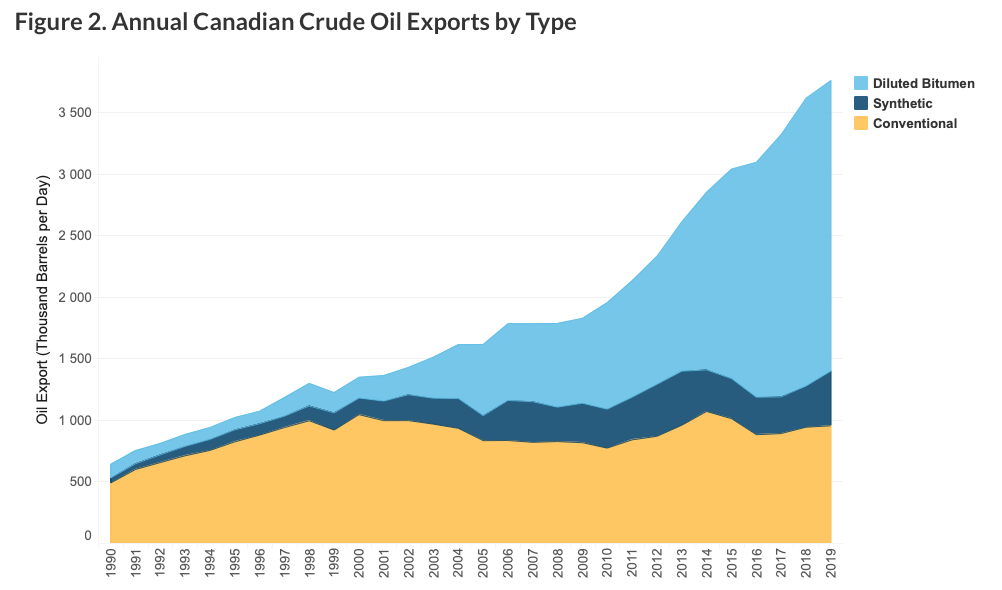

It's also important beyond government spending, as Canadian businesses continue to expand oil and gas extraction and related infrastructure. Production grew 9.2% year-over-year in 2024, and has grown 176% since 1990 and we are continuing to make major oil and gas bets, like the TransMountain expanded system upgrade.

As the C.D. Howe Institute argued in 2022 in Last Barrel Standing?, the cost structure of Canadian oil and gas is such that existing extraction facilities may be able to operate for a long time at much more marginal prices (sub-$40/barrel) than more conventional extraction styles (e.g., some of the newer US sites). As they theorise, "the prevailing price would have to drop below C$10 per barrel before all oil sands operators would choose to cut production."

In other words, the public sector impacts - both on Alberta and the wider Canadian fiscal landscape - can (and if experience is any teacher, will) be very bad, but the private sector context is more complex.

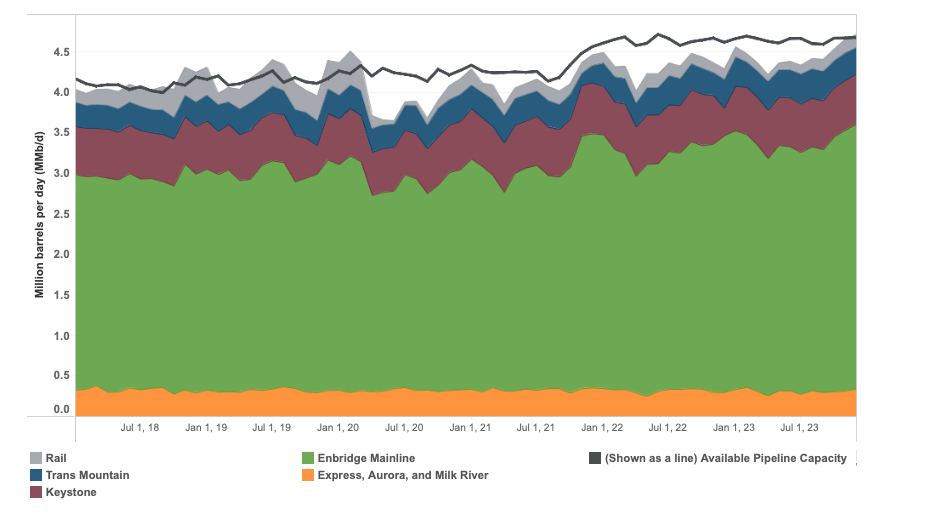

A long-time concern, beyond any question of cost of production, has been transportation capacity. In 2018, the Government of Alberta instated oil production curtailment in order to ensure that storage and transportation assets weren't overwhelmed in an avoidance of a classic "tragedy of the commons" situation.

The completed TransMountain Pipeline's Expanded System will create some significant headroom to avoid this kind of situation for the next few years, expanding the capacity to move Western Canadian oil by another 590,000 barrels a day. (Mb/day). 80% of this has already been contracted by oil shippers - producers, refiners, and marketers - and the other 20% will be available for uncontracted, "spot" shipping on a month-to-month basis.

So, this means that Western Canadian oil (WCS), long hemmed in by a lack of export capacity, will have its long-desired expansion of "tidewater access" and, if predictions hold true, the discount ($18.5 a barrel in early 2024) will be reduced and may even reach close to parity with the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) price of oil now that the cost of transportation has decreased so significantly. But this may only be true for another few years, as TD Bank predicted this year that all new capacity could be eaten up by 2025/2026, meaning further expansions will have to draw on expensive rail transport.

So, the news about a peak oil demand in 2030 isn't great, but is survivable, at least in the medium term, for existing producers.

The rub here is really in the creation of any new production and for this there are a few key factors that will influence the prospects of that side of the industry:

The Varied Costs of Production

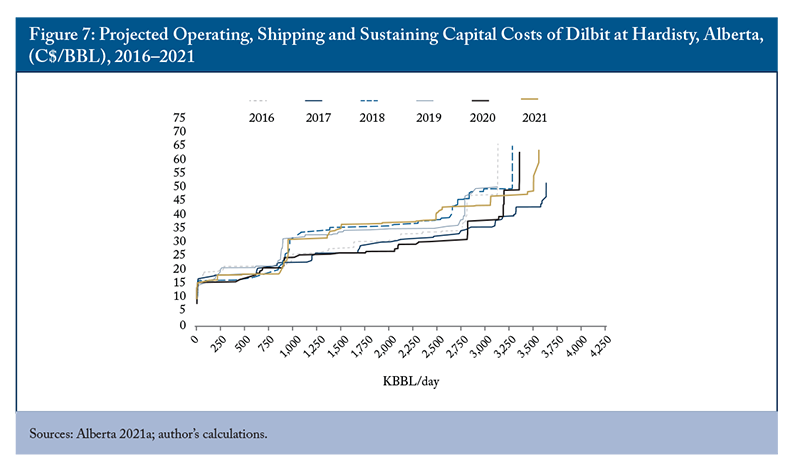

As the International Institute for Sustainable Development laid out in their 2021 report, In Search of Prosperity: The role of oil in the future of Alberta and Canada, the cost of production, despite significant gains made in the past decade, continues to be a huge impediment to oil sands long-term stability and growth.

They make the point that there is a huge variation in the cost competitiveness of different types of oil fiends, and the extraction methods used. They identify that "existing oil sands production is primarily of two sorts: in situ and mining," and that only about "20% of Alberta’s oil sands are amenable to mining, and mining accounts for about half of total oil sands production—a percentage that is steadily falling." In situ, by contrast, is much more complex, tend to be smaller than mining operations, but, once built, are cheaper to operate and upgrade over time.

IISD felt that these large investments, like the proposed and then-withdrawn Teck Frontiers mine, "are less likely to go forward in the future, given high breakeven costs, high upfront costs (and the consequent need for financing), and long-run oil price uncertainty."

In contrast:

Existing operations are a different story, with operating costs having fallen significantly to the point where some SAGD operations achieved operating costs of close to CAD 5/bbl, and integrated mining operations (i.e., mining plus oil upgrading) had costs of under CAD 30/bbl (Birn, 2019). Such operations, especially if they have paid off their initial investments, can survive for extended periods of time, even at the kinds of low prices that punished the sector in 2020.

Refinement - Commodity Quality and Ease of Access

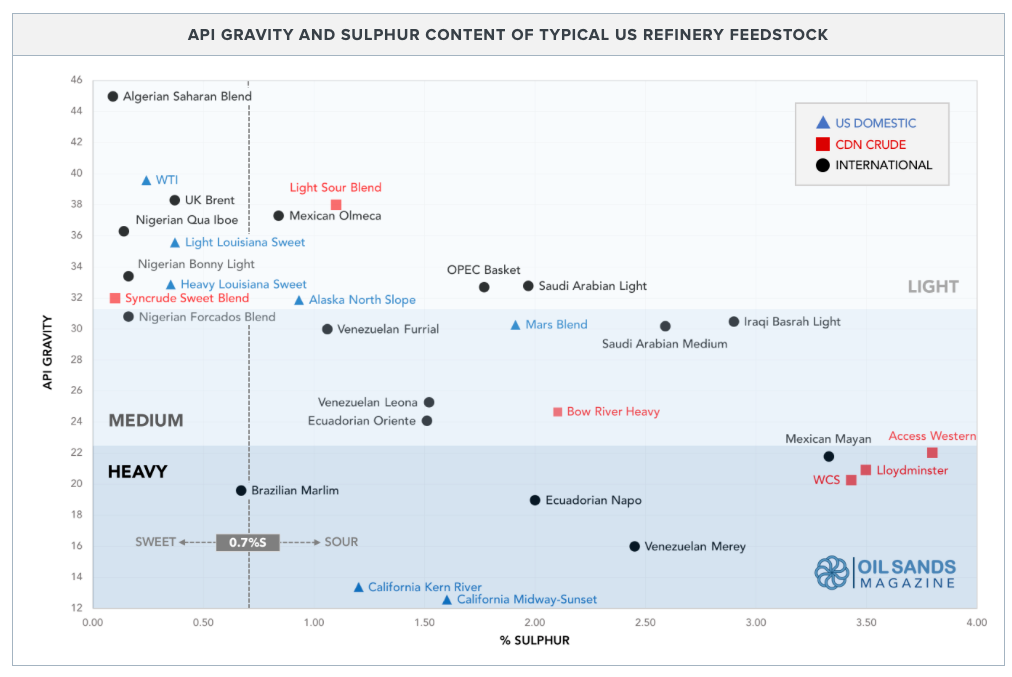

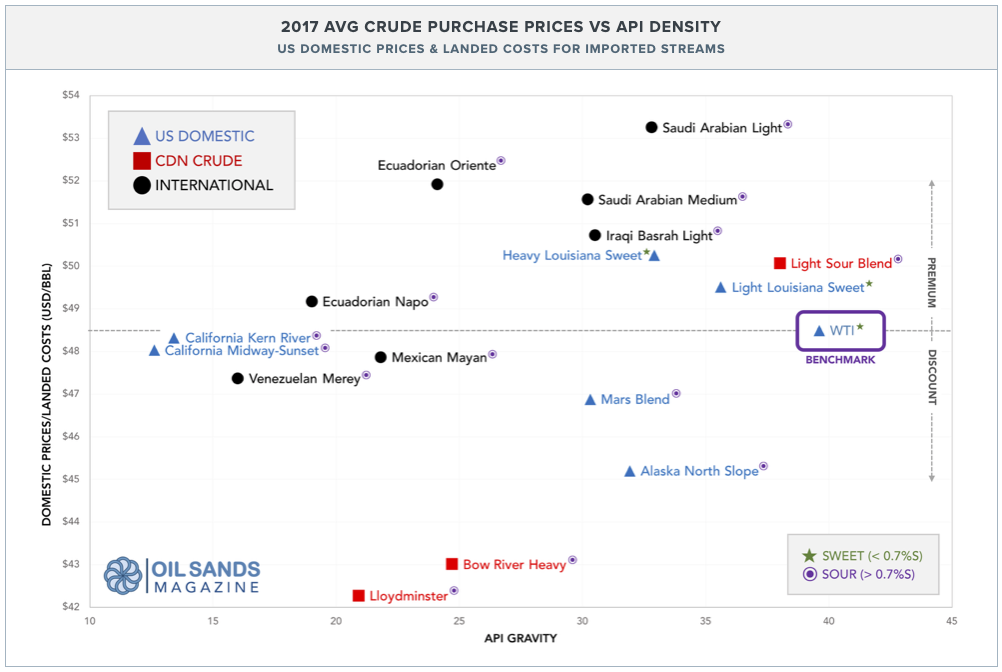

IISD doesn't dwell on the question of refinement as much, but as Oil Sands Magazine has covered in the past, WCS' price differential to WTI has a number of different factors that cause it, one of the most important being quality. Heavier crude oils require more complex (and costly) facilities, when accounting for the two crucial factors of density ("API Gravity") and sulphur content.

Though Canadian oil producers have tried to streamline and harmonize their commodity, the variation in blends does mean a variation in prices on the market, which isn't necessarily a bad thing for some producers, but it plays a role in where – and from whom – refinement can be purchased.

The conventional wisdom seems to be that proximity and logistical ease of access to refineries is the greatest consideration for being able to access. And here we're at a disadvantage again.

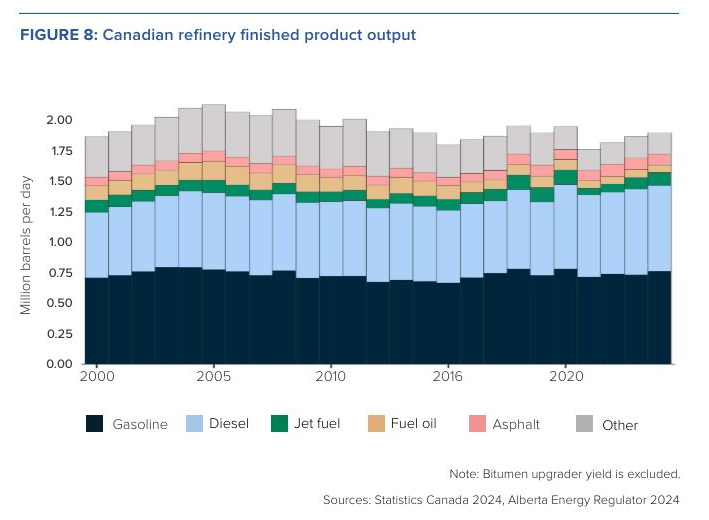

Canada's own refinement capacity has remained largely flat over many years and is increasingly a source of concern for some as the fleet of between 15-18 facilities continues to age. About 20% of Canada's produced oil and gas are refined in the country, but as the Macdonald-Laurier Institute (MLI) has noted, these facilities were largely "not built to handle the heavier crude streams that have come to dominate Canadian crude production growth."

Because Canadian refineries are mostly for our own domestic fuels consumption - already expected to decline under business-as-usual measures - the desire of these facilities will likely wane, as has been predicted by the Canadian Energy Regulator. This means that, in the IEA scenario, Canadian producers have a smaller domestic market for refined fuels and, if trends continue, face a greater and greater reliance on American refineries - and the prices they want to pay.

The Decline Rate of Oil Sands Facilities

A different 2023 IISD report, Setting the Pace: The Economic Case for Managing the Decline of Oil and Gas in Canada helpfully summarizes the context of the "natural" rate of decline for Canadian oil sands facilities. This is how quickly an oil asset is depleted, which impacts not only raw production volume, but also, in some cases, the overall economics of the facility. As they summarize:

The weighted average decline predicted for new Alberta crude oil wells in 2022 starts at 46% in the first year of operation, winding down to 8% by year 10 (Alberta Energy Regulator, 2022c). Across all operations and life cycles, global decline rates for oil fields—the “natural” decline rate—average 8% per year (IEA, 2018). Alberta’s oil sands mining operations are not subject to decline in the same way as wells, and they can more or less maintain steady production levels until their reserves are significantly depleted.

This is important for creating a sense of how much new production is needed to brought on each year to plan for future infrastructure expansions, and therefore maintain an effective and skilled workforce, have the right relationships with capital providers, and so on. Using industry data, IISD projected that:

"If no new oil and gas fields were developed, Canadian production would peak at about 60 billion barrels of oil and gas in 2023 before decreasing by about 20% by 2030 and 70% by 2050."

The Cost of Capital

In Search of Prosperity, again, lays out one of the major challenging factors for new oil facilities in Canada going forward: the cost of capital. Unlike gas, which, for all of its consternation, can still sometimes get capital easier, oil is not only massively capital intensive - exceeding $30 billion in annual investment in recent years - but subject to increasing amount of scrutiny, not only on the side of the producers, but also financiers.

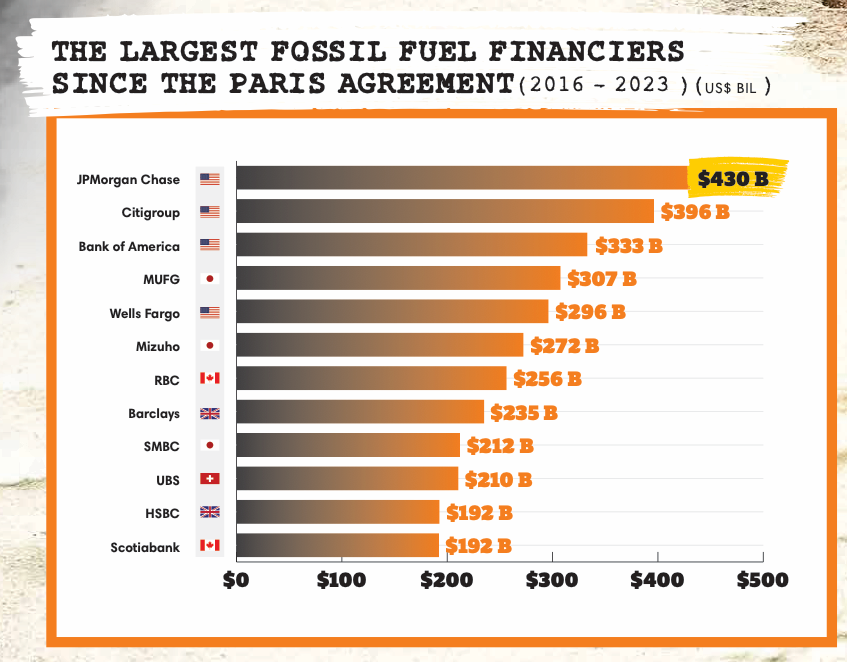

The Rainforest Action Network, Shift, and many other organizations actively monitor the investment decisions of major banks, pensions, and other financial institutions. As the 2024 edition of Banking on Climate Chaos outlines:

The 60 biggest banks globally committed $705 [billion] USD to companies conducting business in fossil fuels in 2023, bringing the total since the Paris agreement to $6.9 [trillion].

Two of the largest global recipients of this were Enbridge, with $35 billion USD in financing committed in 2023, and TC Energy Corp, for $15.25 billion USD. Of the twelve largest financiers, three Canadian banks made it into the list. More relevant to Canadians, though, is the financing of Canadian oil sands projects. RBC was the largest financier within Canada and the eighth largest in the world, with global leader JP Morgan Chase coming in just behind.

In Search of Prosperity's analysis was particularly interesting, though a little dated now, in noting that oil sands investment had been in significant decline from 2014-2021- though it had a record year in 2023. As part of the headwinds that would-be Canadian oil borrowers face, they identified two major factors:

- A shrinking pool of capital, as more and more pensions and particular insurance companies (several of which have said they will no longer insure oil sands projects).

- And the Redwater case, where the Supreme Court ruled that oil and gas companies had a responsibility to pay for their environmental remediation costs as part of a bankruptcy proceeding and not just their creditors, has now significantly increased the perceived risk of a lending to a company with significant public liabilities to deal with.

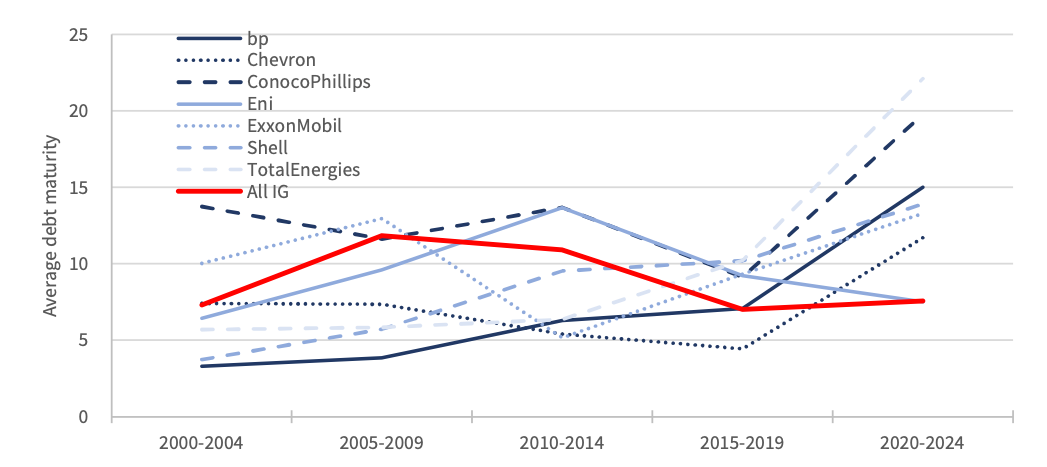

One aspect I couldn't find Canadian data on, but may also be true here, as it is globally, is that the oil and gas majors are tending to lengthen their debt maturity for issued bonds. Interestingly, European oil majors are apparently moving more and more toward a hybrid approach of bonds and equity, while Canadian producers apparently tend to favour an equity-first approach.

As the Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute writes on this, "Oil producers have increased their use of this product in the past few years, paying more to issue debt which will not dilute their credit ratings. This presents negative convexity risk for investors, meaning their exposure is increased in poor market environments."

This all points to, in varied and complex ways, (1) a likely higher cost of borrowing in the future for Canadian oil and gas production related to all of the factors above and (2) increased risks – forgetting the genuine threat of climate change for a moment, even – to the lenders entering into this highly volatile and uncertain sector.

Putting it All Together

The global energy picture is never simple. The more I learn about it, the more amazed I am that our system of moving electrons and molecules around to power our civilisation works at all. But in watching it all, and particularly after this most recent IEA report, the dangers of our current economic and ecological model feel more frightening than ever.

The IISD's Setting the Pace report I think spells out some of the more concerning economic impacts to Canadians clearly. They argue, building on prior modelling from Aaron Cosbey, that even a more moderate price decline would cause significant pain if it were matched by significant price volatility.

In the volatile scenarios, GDP contributions from the oil and gas sectors in Alberta drop by an annual average of 19% to 21% out to 2050 compared to the reference case, or an average of CAD 21.8 billion to CAD 24.3 billion—more than five times the impact of the stable price scenario. Investment in the oil and gas sectors was particularly strongly affected, dropping 26% to 30% per year on average, or CAD 9.6 billion to CAD 11.2 billion. Alberta’s net exports also suffered in both volatile scenarios, and the province’s oil and gas sectors shed between 21,000 and 24,000 workers on average compared to a steady price scenario.

They, and others, are clear that the exact numbers - because of their immensity - are almost irrelevant. What's the difference between a 19% or a 21% decline in sectoral GDP to an unemployed person? Very little.

This is why a responsible and just transition, which includes acknowledging the reality of declining global oil use is so key. We can scream from the rooftops as loudly as we want things to be different, but that oh-so-cruel invisible hand appears to be pushing down on us with ever-greater strength.

The passing of the Sustainable Jobs Act recently (again, check out Megan Gordon's piece) is an important milestone here, but only just the beginning. It is an attempt, however imperfect, to grapple with the reality that Canadian workers, businesses, and governments all must: that our economy is changing in profound ways that are not entirely in our control. And far from a top-down policy agenda, as Oil 2024 shows, there are a number of self-sustaining forces that are driving shifts, too, that cannot be stopped.

Sadly, I don't expect the full reality of these challenges to sink in to Canadians just yet.

I think the momentum of the industry is still too strong and the numbers too big to see the cliff we appear to be headed towards. But I think for those of us who take the well-being of our country and its people seriously, not to mention our planet, these numbers give us the basis upon which to start laying concrete plans.

We have some room for optimism - this year Alberta completed their shockingly fast transition off of coal-powered electricity and both the national and provincial governments have done meaningful, and yes, incomplete, work to support impacted communities. We can build from this, the forward-looking plans of organizations like the Pembina Institute, and the The Transition Accelerator, and set ourselves on the pathway to where we need to go.

I feel lucky that I already get to do a little bit of that work every day.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.