Chrystia Freeland, Canada's Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister, made a splash on October 7th with the endorsement of, and a high-level commitment to continue work on, investment guidelines related to sustainability. For those of us in the weeds, this is the Canadian Sustainable Finance Taxonomy.

Toronto StarIan Bickis The Canadian Press

Toronto StarIan Bickis The Canadian Press

A taxonomy, as the Sustainable Finance Action Council (the body appointed by the Government of Canada to deliver advice in this area), said of them:

A green and transition finance taxonomy is a tool that is meant to help mobilize the allocation of capital to economic activities that are consistent with national transition pathways and climate mitigation objectives. It can be advanced by government, the private sector, or both, acting jointly.

More specifically, Climate Policy in Action (CCAP), identifies it as:

a classification of a list of economic activities that are considered environmentally sustainable for investment purposes. In general terms, it establishes a framework for enhancing market transparency, reducing uncertainty and incentivizing financing to a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy. The taxonomy helps commercial banks, financial institutions, asset managers, private equity funds, insurance companies, pension funds, corporations, angel investors, public trusts, national development banks, microfinance institutions and credit unions among others to identify truly sustainable finance opportunities and provide them with a transparent and credible list of prospective sustainable investments.

The taxonomy would be used in a complex series of ways, for regulators, individual companies, investment analysts, and others, but fundamentally it provides a common framework for everyone to refer to, like the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is for psychiatrists and mental health practitioners.

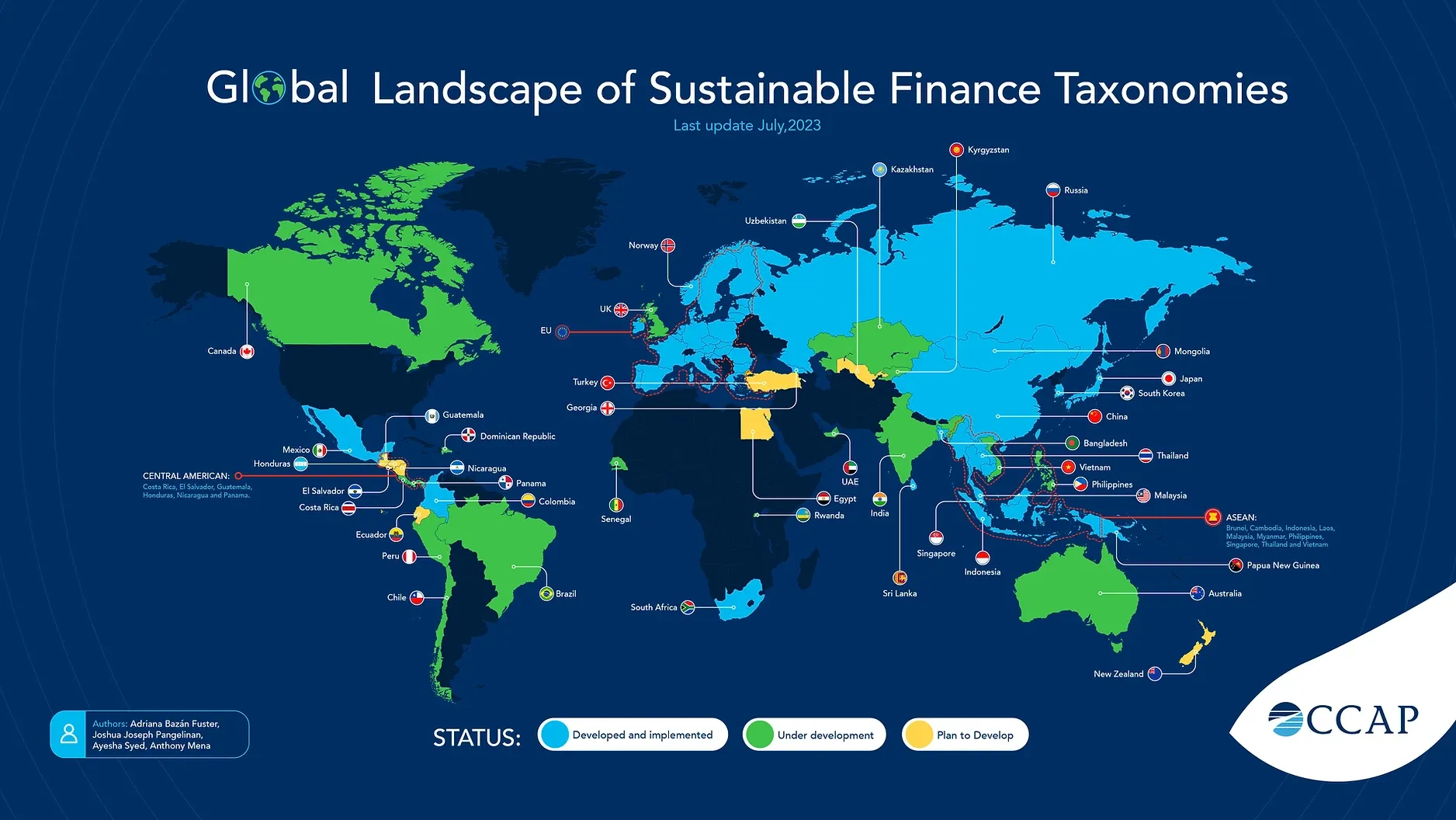

It builds on and adapts from work started in Europe through the European Green Deal, which had sustainable finance as a key pillar. Since their release of a taxonomy in 2020, numerous other countries and regions have gone on to develop their own. Canada and the United States have been the laggards in terms of large, advanced economies in not having one.

As one of the major leaders in this effort, the Canada Climate Institute's Jonathan Arnold, wrote on LinkedIn that the endorsement was a "big and long-awaited day for sustainable finance in Canada," and called out two optimistic elements of the Government's announcement:

On process, the federal announcement emphasizes the need for a credible, independent, and science-based body to develop the taxonomy. Establishing this credible governance structure will underpin the entire effort.

On content, the announcement largely aligns with the "green" and "transition" analytical framework that we helped develop in partnership with the Sustainable Finance Action Council. Importantly, the announcement stresses the need to exclude new fossil fuel projects. [emphasis original]

The Institute followed up in their press release with further support, but also noted that there's much more work to be done still. As Jonathan wrote for them earlier this summer, specifically keying in on the challenges around how investors can navigate investments in the oil and gas sector:

If the oil and gas sector is going to reduce its upstream emissions—which it must if the world is to protect the next generation from catastrophic climate change—it will need to invest capital on an unprecedented pace and scale. Yet there’s a significant risk that additional investments in this sector could extend or lock in future emissions and compromise Canada’s chance of hitting its national and international climate commitments.

He, and basically everyone else, emphasize the need for certainty around what's "in" and what's "out" in terms of a credible, net zero-aligned investment opportunity.

Besides what the definition of "economic reconciliation" is (and not unrelatedly), this is probably the single most politically polarized question in the entire country.

Can you invest in oil and gas at all, or at least in specific aspects of it, and still be considered green?

The Action Council had to walk an incredibly delicate balancing act between political realism – oil and gas are massive economic and political forces in Canada – and a commitment to the science and urgency of climate action – we must reduce our emissions.

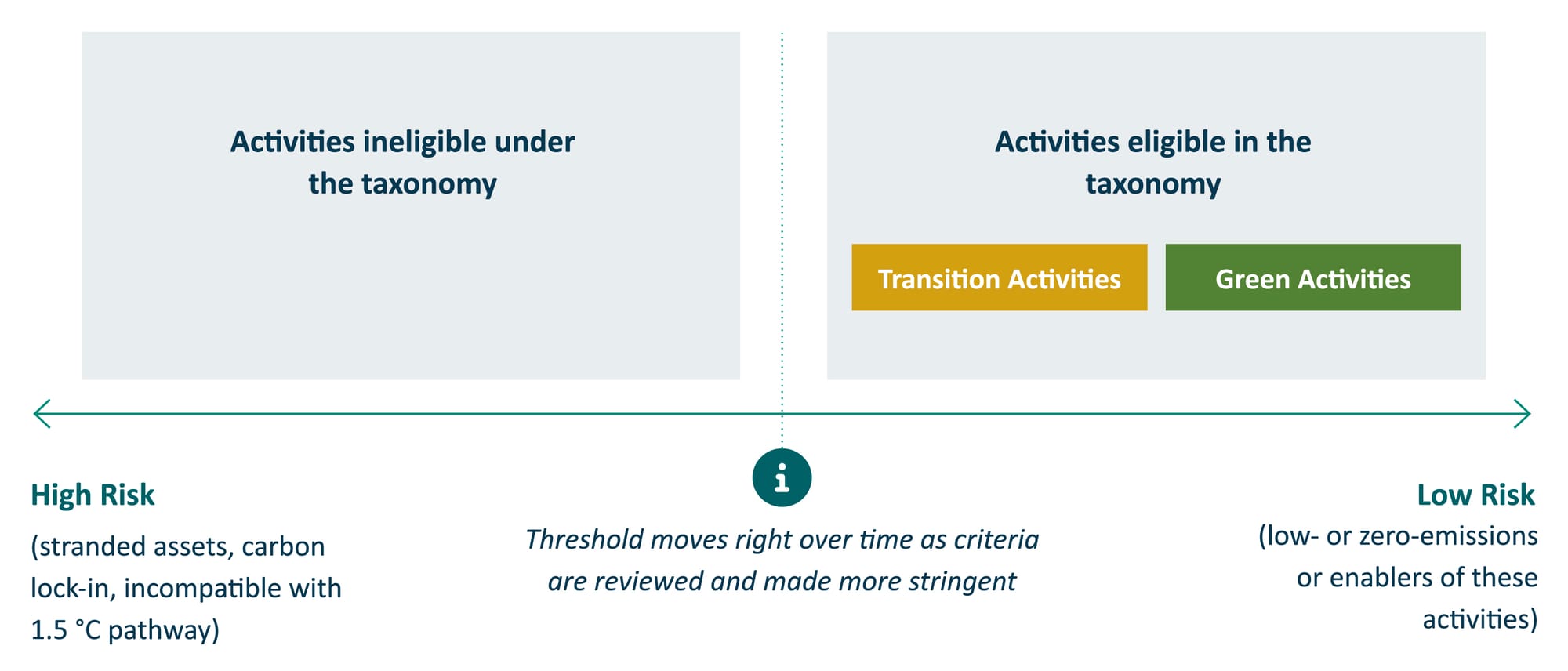

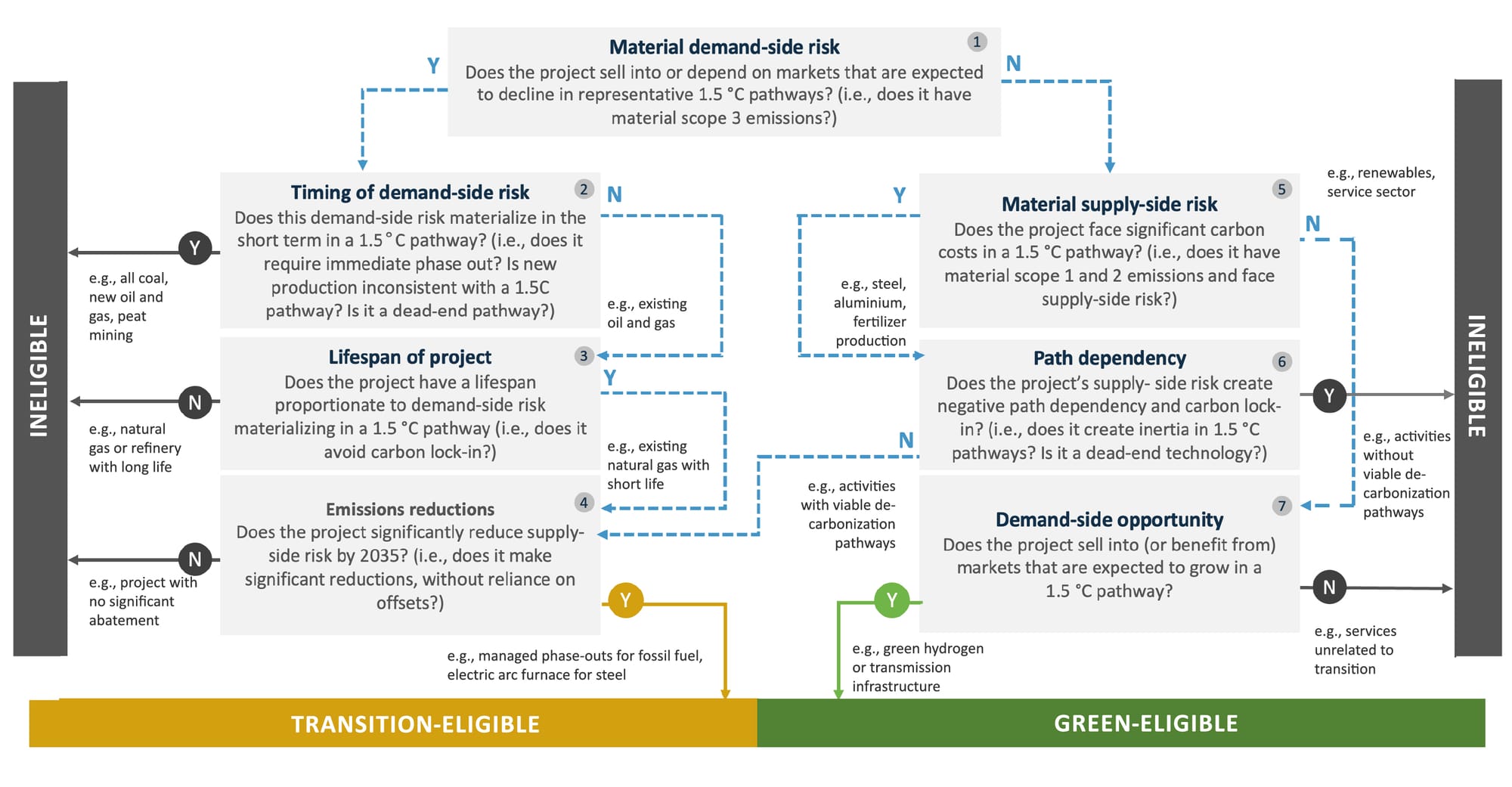

In the end, they tried their hardest to walk this balance by highlighting two categories of investments: those that are in transition, and those that are, by any reasonable definition, truly green.

To get the taxonomy’s transition label [which is unique to Canada], an oil and gas project would have to result in transformational emissions reductions. Specifically, the facility as a whole would need to significantly reduce its Scope 1 and 2 emissions over time, to a level that is consistent with 1.5°C pathways. These are the emissions that oil and gas facilities have direct control over — (the emissions these facilities don’t have direct control over, known as Scope 3 emissions, matter as well, as we’ll see).

A project that hit the mark there would have to be able to credibly show that both the absolute and relative greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions it produces credibly lower over time to meet our global goal of listing warming to 1.5 celsius.

That's a tall order, but with BC's regulations on net zero oil and gas projects, the federal potential for emissions cap for the petroleum sector, and other rules, it is actually possible that facilities can be built with nearly-zero on-site emissions. It's the use of those fuels after they're extracted that are the much larger challenge.

But that's where the whole suite of climate action policies also contribute: we're working to decarbonization buildings, transportation, and industry through other mechanisms.

As someone in the trenches in those other sectors, I'll be the first to tell you that it's hard work, but with more clarity at the level of capital markets (which is what the taxonomy does) we will also hopefully see a trimming of various other investment streams (e.g., new gas plants, high-carbon transportation options, etc.) and corresponding growth in climate-aligned ones.

Working In Practice

The original SFAC report has a few examples of what the execution of the taxonomy, which would include a complex but transparent governance system, are helpful in understanding how this would work.

In a situation where an issuer (e.g., a company) wanted to borrow money through a bond to undertake a full-on green, or transition-related activity, they imagine the issuer would develop their offering using structures from "established global process guidelines, including the Green Bond Principles and the Climate Transition Finance Handbook published by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA)."

ICMA

ICMA

Using those guidelines, the issuers would publish their offering ("hey, buy our bond") and explicitly lay out how that issuance aligns with those standards and explain how the entity planned to use the money.

If you want to see a framework like this, see what the City of Vancouver has done through their green bond issuance. They break down a series of both social and green thematic areas (.e.g, "climate change adaptation," "affordable housing") and then describe the range of activities that they'd do in that area. In some cases, a bond is for one, big thing – "we're building a highway!" – and in others, like the City of Vancouver, it's for a whole range of things, so, there will generally be a range of specificity. But importantly, with your framework you're creating exclusions: you're guaranteeing you won't do things outside of what you promised in your framework.

As SFAC continues, a bond issued like this would include:

- The categories of green and/or transition projects eligible for funding with the bond proceeds as well as the corresponding screening criteria based on the taxonomy's specific and ["do no significant harm"] requirements;

- Description of the governance and management of the issuance process, including the evaluation and selection of eligible projects, the DNSH assessment methodology, the review of framework-related reports and disclosures and the monitoring of issuances and evolving market practices; and

- Details on the procedures to ensure that proceeds are only used for eligible projects, as well as an explanation of the frequency, nature and scope of reporting on the use of proceeds and associated environmental impact.

Before the bond fully goes to market, the framework would likely be subject to some sort of external review and, if approved, an endorsement about its alignment to these high-level principles from different actors.

Once the money is in hand, then the issuer would release reports and updates to say how they're using the money and the impacts of it, usually with some external auditing.

What comes next?

The Sustainable Finance Action Council released, in 2022 (!), a roadmap report to how to actually build a taxonomy. They gave high-level principles, laid out a process, and gave examples and key considerations.

Canada.caDepartment of Finance Canada

Canada.caDepartment of Finance Canada

To truly succeed, they said that a taxonomy would have to align to the following principles:

- Holistic – Do-No-Significant-Harm (DNSH) criteria addressing environmental, social, and Indigenous objectives.

- Dynamic – A built-in review process to ensure the Canadian taxonomy is updated as the landscape evolves.

- Transparent – A governance structure that is transparent, efficient, adaptive, and results-oriented; safeguards scientific integrity; and engages with key stakeholders, including provincial and territorial governments, civil society, financial market participants, industry, and Indigenous partners.

- Interoperable – Be interoperable and broadly compatible with other major science-based taxonomies and frameworks globally, while reflecting Canada’s own economic context.

- Comprehensive - Cover transition and green activities that make a material positive contribution to climate change mitigation, addressing high-emitting sectors.

- Credible – Clear, rigorous, and credible science-based criteria that align with limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, with no or low overshoot and all relevant emissions scopes considered. Any activity which receives the green or transition taxonomy label must be scientifically defensible as being aligned with this.

- Usable - Mobilize capital toward the net-zero transition.

While the Government of Canada has again upheld these principles in their announcement, they will have to fight it out – in an increasingly fraught political – to get them fully implemented. Many people are profoundly frustrated with how long it's taken the government to get even this far, and I'm completely with them, but I remain optimistic that we're seeing the big, slow ship of Canadian finance beginning to move in the right direction.

Even in the likely (but not certain) event of a Conservative national government in the next year or so, Canada can only "go it alone" for so long. The European Union, China, and Japan, three of the largest markets in the world, all have taxonomies that are beginning to structure what people can and cannot invest in. And while the United States is still a laggard, there's huge activity at the state level in many different directions.

More importantly, as I spoke about on the CBC earlier this year, consumers and individual financial institutions, like Vancity, are moving ahead of government and the bigger financial players on this. It will never be enough on its own, but it's one more brick in the road.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.