I was a bit delayed in writing this because I wanted to write this as a preparation for speaking at the Global Environmental Facility's 7th Assembly here in Vancouver. I was lucky enough to be asked to sub in for the inimitable Cristina Gómez Garcia-Reyes on a panel put on by UNIDO about engaging industry in the Montreal-Kunming Biodiversity Framework.

Now, biodiversity isn't my day-to-day, but I had the privilege to sit on the Global Commission on BiodiverCities by 2030, an initiative of the President of Colombia and the World Economic Forum. The Commission's work ended up being one of the most fascinating projects I've ever had the privilege to participate in and culminated in this spectacular report that the Commission fed into.

https://www.naturepositivecities.org/home

I'll say more about the report in a moment, but first, I want to really drill into a few key concepts.

What is biodiversity, and why does it matter?

When we're talking about biodiversity, there are innumerable ways to consider to define and discuss it. There are also, importantly, a huge number of overlapping terms. For myself, I like to situate biodiversity as a facet of nature - something even broader and more nebulous, but still - biodiversity is a way of conceiving of (and measuring) nature and its health.

Last year, Cristina Gómez Garcia-Reyes and I discussed this at length on the NewCities podcast.

Cristina gives some really wonderful answers about what nature is there, but throw in another source that I really love and reference frequently (and with relevance to businesses) is the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD).

I like the TNFD in that has to navigate very technical matters and distill them to an audience of non-experts. They draw on the definition of nature used in the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) from Díaz, S et al (2015).

The natural world, with an emphasis on the diversity of living organisms (including people) and their interactions among themselves and with their environment.

Furthermore, they outline nature as having four "realms," which are all interconnected, and all of which human society depends upon.

And so if that is nature, then what is biodiversity?

From the same Diaz et al paper which defines nature, and developed in 2015 developed for the IPBES' conceptual framework, they define it as:

The variability among living organisms from all sources including terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are a part. This includes variation in genetic, phenotypic, phylogenetic, and functional attributes, as well as changes in abundance and distribution over time and space within and among species, biological communities and ecosystems.

In the many other definitions you will see, you will consistently see "variability" as the operative word. Biodiversity is, in the most general possible terms, the variance among the different types of life in a given context. Generally speaking, the more the better.

What is the present state of biodiversity?

The IPBES does assessments, much like the IPCC does, on a rotating basis of the state of biodiversity and nature around the world. In the most recent assessment from the end of 2019, the situation cannot be described as anything other than dire.

One of the most startling graphs that they show is related to extinctions.

While we have to reconstruct some data historically, we can see that as our measurement gets better it also coincides with the most rapid and terrifying decrease of species. In some cases, it's more than a 5x increase in total extinctions. This corresponds with the framing of our current era as the "Sixth Extinction."

But biodiversity is so much more than just extinctions; it reflects a huge array of ecological conditions, sadly, almost all of which are trending in the wrong direction. The essential ones, identified below, are the Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs) that the IPBES has determined collectively tell a coherent and comprehensive story of the state of global biodiversity.

Two things stand out to me as I re-read the assessment from 2019 (which we have built our understanding from, perhaps most concerningly of late around ocean acidification):

Firstly, the speed at which this transformation of nature is occurring. As the Assessment (pg 228) writes: "Nature has faced multiple drivers of change from human actions. Many of these drivers have accelerated rapidly. The same is true for many changes in nature. Indeed, for some facets of nature, the changes have accelerated so rapidly that as much as half the total anthropogenic change in the whole of human history may have taken place since the mid-20th century." [emphasis added]

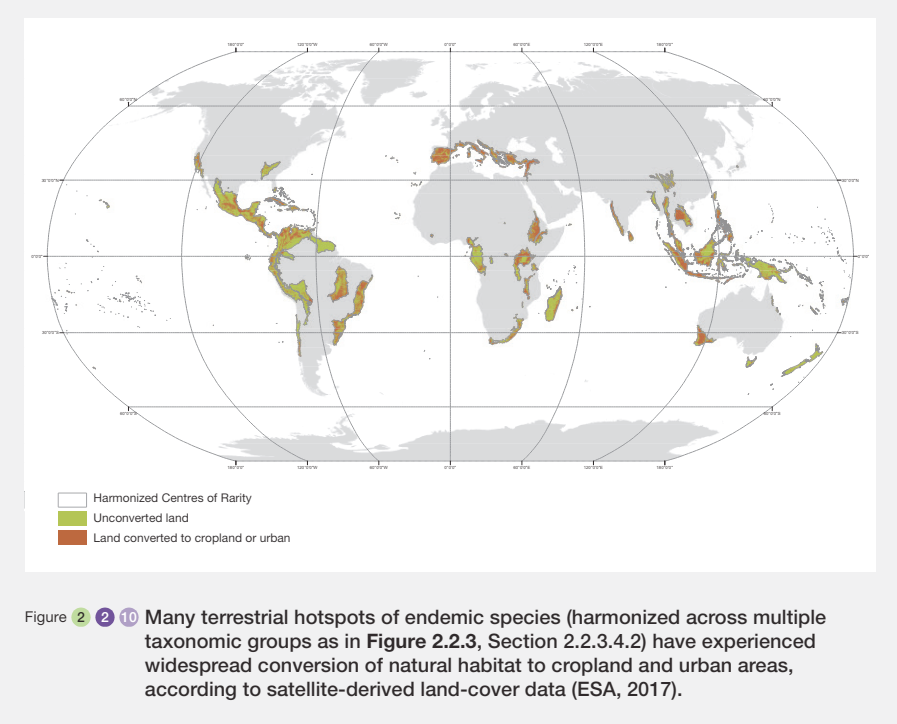

Secondly, it is the extent to which humans are dramatically altering the planet at this speed. The full chapter on impacts and trends from the Assessment leverages a variety of maps and statistics to showcase where and in what aspects biodiversity has been impacted. One particularly striking illustration, below, shows biodiversity hotspots around the world and the extent to which they are experiencing conversion to cropland or urban spaces.

I think cropland is a particularly sticky aspect of the assessment because, from the perspective of pure biomass, there are ways to look at this as a net increase to the earth's biological output, as the Assessment notes (pg 235): "the biotic consequences could be much greater than such a small net change might suggest: agriculture has increasingly channeled terrestrial [Net Primary Product] through a relatively small set of species, reducing the diversity of forms in which that NPP is available to the species in ecosystems."

Another assessment that I think is worth taking stock of is the Dasgupta Review on the Economics of Biodiversity. In the spirit of the pioneering Stern Report from 2006 on the economics of climate change, it looks at the economics of biodiversity from the perspective of societal risk and value. Like all of these grand assessments, the full report is over 600 pages, but the summaries are helpful and add another lens on biodiversity loss: value.

Like the IPBES, the Dasgupta Review situates itself on a fundamental premise: humans, and human society, are part of nature, and we depend on its holistic health (not just one or two aspects) for our civilizational survival. Full stop.

One thing I enjoy in part of the abridged review is an aside on the question of absolute value; in their words, it is absolutely meaningless. It's worth reading in full:

Absolute values of portfolios carry no information; only portfolio comparisons do. The value of a marginal change to the biosphere is meaningful because it is presumed that humanity will survive the change to experience it, but the matter is different when it comes to valuing Nature as a whole. It may be because growth and development economists ignored our place in the natural world, environmentalists some years ago were tempted to value the whole of Nature, to show that it is of great economic worth. In a widely cited publication in Science, the authors estimated that the global flow of the biosphere’s services was, towards the end of the 20th century, worth US$16-54 trillion annually, with a point estimate of US$33 trillion (Costanza et al. 1997). As that figure was larger than global GDP in the mid-1990s, we were meant to appreciate the economic significance of natural capital.

The estimate is a case of misplaced quantification. As the authors recognise, if Nature is destroyed, life would cease to exist. But then who would then be here to receive US$33 trillion of annual benefits if humanity were to exchange its very existence for them? Economics, when used with care, is meant to serve our ethical values. The language it provides helps us to choose in accordance with those values. Despite recognising this, the authors of the paper imply that the biosphere is valuable because it can be imputed a large monetary value. That is to get things backward.

Measurement problems are also rife in estimating the stock of many kinds of natural capital (fisheries stocks in their national waters are generally not recorded by governments), but it is far better to work with rough and ready figures than to ignore whole swathes of capital goods by pretending they do not exist. Unfortunately, the macroeconomic theories of growth and development that have shaped our beliefs about economic possibilities and the progress and regress of nations do not recognise humanity’s dependence on Nature. The Review corrects that mistake. [emphasis added]

So, they're on a corrective mission with regard to how humans understand our relationship to nature and that corresponding relationship to the economy. But what does that relationship look like in material terms? They have answers.

As they say: "Figure 9 displays the authors’ estimates of global accounting values per capita of the three classes of capital goods over the period 1992 to 2014. It shows that the value of produced capital per capita doubled and human capital per capita increased by around 13%, but the value of the stock of natural capital per capita declined by nearly 40%."

In short, our global economy - and especially the wealthiest and most powerful actors within it - continue to benefit at the expense of nature (and, though out of scope for Dasgupta et al, the poor).

What do businesses have to do with biodiversity?

Dasgupta, the IPBES, the IPCC, and numerous other global assessments, analyses, treatises, and otherwise all are firm on the cause of this precipitous decline: humans are consuming too much and not replacing that which we take from nature.

Dasgupta calls it "unsustainable economic development," and considers three factors: "population size; per capita GDP, and the efficiency with which we convert the biosphere’s goods and services into GDP; and the extent to which the biosphere is transformed by global waste products;" while the IPBES identifies five interconnected factors in the form of "changes in land and sea use; direct exploitation of organisms; climate change; pollution; and invasion of alien species."

All of these relate to the way humans use (and dispose of) the resources we take from nature. As Dasgupta aptly summarises:

"Globally, Nature’s subsidies amount to an annual US$4-6 trillion, or approximately 5-7% of global GDP."

That's speaking about the global economy in a macro sense, but what about its parts? If we collectively rely on nature for our economic prosperity, then that's also true in an individual and corporate sense, too.

In 2020, the World Economic Forum put out a bold new paper talking about the relationship between the economy and nature.

The New Nature Economy series came in part from the Forum's annual survey of global business leaders and the risks and concerns that they were most worried about. Consistently biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse was ranked as one of the top five (separate from climate change) threats humanity will face in the next ten years.

Their headline findings are powerful:

- We are reaching irreversible tipping points for nature and climate, and over half of the global GDP, $44 trillion, is potentially threatened by nature loss.

- 80% of threatened and near-threatened species are endangered by the three systems, which are responsible for the most significant business-related pressures to biodiversity; these are also the systems with the largest opportunity to lead in co-creating nature-positive pathways.

- 15 systemic transitions with annual business opportunities worth $10 trillion that could create 395 million jobs by 2030 have been identified that together can pave the way towards a people- and nature-positive development that will be resilient to future shocks.

- $2.7 trillion per year through to 2030 will be needed to scale the transitions, including to deploy the technological innovation critical to 80% of the business opportunity value identified.

The Dutch Government and National Bank took this a level further by examining the specific risks of biodiversity to their financial sector. Their thinking here is helpful in laying out the cascade of risks and how they apply not just to the economy, but to both a specific and cross-cutting sector like finance.

Both the scale of value at risk and the potential opportunity in play are truly staggering. Importantly, much of this work is in addition to investments that must be made to address climate change - and as the report says, addressing climate change on its own will be insufficient (and cataclysmic, in fact), if we do not also address the crisis of the ecosphere.

What does a business that takes biodiversity seriously look like?

In biodiversity, as with any major systems problem, it's important to think in scales. I often find people quickly get polarized into thinking about the system as a whole, or some particular level - usually organizations or individuals. In this sense, my own question above is only one piece of a larger puzzle: we need a sustainable society that takes biodiversity seriously, and within that, businesses that do so will be a critical aspect.

With that said, let's quickly touch on two scales of what a biodiversity-serious society will need to do.

At the global level, we're now lucky to have a clearer idea through the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, itself a component of the Convention on Biological Diversity. The framework lays out four goals, nicely summarized here as:

- Halting human-induced extinction of threatened species and reducing the rate of extinction of all species tenfold by 2050

- Sustainable use and management of biodiversity to ensure that nature’s contributions to people are valued, maintained, and enhanced

- Fair sharing of the benefits from the use of genetic resources and digital sequence information on genetic resources

- Ensuring adequate means of implementing the GBF are accessible to all parties, particularly least-developed countries and small island developing states [and closing the $700 billion annual biodiversity funding gap.]

Not specifically called out in these four goals, but woven throughout the Framework and referenced constantly in the IPBES' work is the critical importance of Indigenous sovereignty in biodiversity protection. As Canadian Senator Rosa Galvez reminded us recently, Indigenous leadership and knowledge are essential to biodiversity protection, especially since Indigenous peoples "steward approximately 20% of the planet, but this relatively small share contains 80% of the world's remaining biodiversity." Indigenous Climate Action was emphatically clear during the Montreal Conference of Parties (COP) to the UN Biodiversity Convention: biodiversity can only exist with 'Land Back' to Indigenous peoples.

Also at the local level but through a more Western lens, is the BiodiverCities by 2030 Insight Report that I worked on with the Global Commission and Forum.

It tries to operationalize some of these ideas not just through the lens of cities, but how cities interact with the private sector. We developed a framework of three 'systemic shifts' that would be required for cities to think about and areas of work that they could do internally, through coordination, and in enabling others.

Each of these could have a PhD written about it in and of itself, but a general takeaway I came away with from this is how much our governance systems need to radically transform to address these problems. Our siloed approach to nature - and the often stilted, contradictory goals within those silos - is no longer fit-for-purpose (if it ever was) in the 21st century.

Lastly, we turn to the actual role of businesses.

The World Economy Forum's second report in the New Nature Economy, The Future of Nature and Business is one of a few key reports that discusses this. Frankly, the answers are exciting. Because of the scope of the topic, there are distinct areas of action broken out thematically:

- Nature-positive food, land, and ocean use system

- Nature-positive infrastructure and built environment system

- Nature-positive energy and extractives sector

The report is clear that transitions and transformations in each theme must be underpinned by significant global investments of up to $2.7 trillion USD per year going forward. And within that investment, particular businesses and sectors will have especially important leadership roles.

Weaving between the systems level of the global economy and the work of individual businesses, the Forum's report makes clear that, first and foremost, a much stronger regulatory system is needed globally to ensure effective protection of biodiversity. A "choose your own adventure" is no longer available to us as a global civilization - we need to stay coordinated and understand the biosphere as something we collectively live within (and therefore play a role in managing), not as a cost-free dumping ground and extraction site.

With a strong regulatory system in place that can balance the field, realign incentives, and create a fair playing field for all, then new opportunities can emerge. And, having worked in climate change, there is an exciting mix of opportunities for businesses not to just do well, but to do good - if they are willing to do the hard work of looking at the systems they exist within.

I think that's where the simplest (and still profoundly complex) starting point is: measuring.

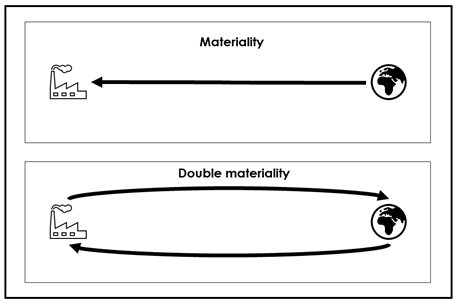

This brings us back to the TNFD, which is designed to do exactly this. Based on the successful, and increasingly integrated, Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the TNFD tries to build a framework through which businesses can conceptualize, measure, and act where their risks are greatest. There are critiques of this kind of system (which I think we need to deeply understand) around the question of materiality: are businesses only responsible for the risks that nature creates for their own business operations, or are they also responsible for the risks of their actions (both individually and in the aggregate) to the world itself.

This is the question of 'double materiality.'

Grantham Research Institute on climate change and the environment

Grantham Research Institute on climate change and the environment

For my own part, I emphatically believe that Milton Friedman was wrong and that the sole responsibility of a corporation is not only to its shareholders, but indeed also to the world. Because, as every piece of literature cited in this article makes very clear, a business, just like an individual, cannot exist outside of society, and nor can any of us exist outside of nature.

And so the TNFD walks a tightrope between this question, though I hope it will one day recognise it more emphatically. And even with this clearer focus on the risks that degradation of nature presents to businesses, I think it still provides a helpful lens and framework for action.

Fundamentally, all the TNFD does is create a structure for 'disclosure;' a way for businesses to talk about the risks they face and how they are addressing them.

As you see the flow of actions and thinking, you can see how a business would start to build out a mental model of their relationship to nature, identifying their dependencies, and then start to walk through the steps they can take to reduce those with targets, metrics, and data underpinning each.

The individual responses of businesses to this will be wildly different, but these frameworks - critically underpinning by strong regulation and government leadership - do seem to me to be a way for us to scale, both up and down, the reorientation of nature we need.

Speaking as a British Columbian, watching my province burn, the last thing we must remember is the urgency with which this must be done.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.