TL;DR

- Fossil fuels remain the largest single source of energy in the world, but the fundamental structures of demand are at play that will change that over the next decades

- Insisting that emerging economies will use the same fossil fuel-delivered development strategies as today’s wealthy countries misreads the current technological and economic context

- China’s pursuit of renewable energy dominance globally is a bet on the future, and their crushing strategic position is an existential threat to the economic security of countries like Canada and the US

- The pricing dynamics of oil and gas are not likely to be kind to Canada in the coming decade; we need to chart a strategy beyond boom and bust commodity price-taking.

What The Hell is Going On?

Are we in a global energy transition? Is the hype over? What the hell is going on with the world’s energy system — and what does it mean for “us”?

This is the swirl of of conversation that I find myself in almost daily.

The back-and-forth on forecasts and data sources and differences in methodology can be exhausting, particularly when people’s preferences change so constantly. At the start of my career, people working on renewable energy tended to dislike the International Energy Agency (IEA) because it consistently underestimated solar and wind installations.

Today, many in the petroleum sector tend to reject the IEA for exactly the opposite reason.

The IEA is not alone for being under the microscope. With the whipsawing nature of global politics and markets right now, the amount of noise and change can make it feel impossible to actually have a sense of what's going on.

Because there's a growing focus on energy literacy, particularly for leaders, I wanted to go to a variety of different data sources and answer the question that many are asking: are we amidst a global energy transition?

As you'll see, I believe we very much are, and the consequences for a oil and gas producing country like Canada could well be dire if we don't wrap our heads around this quickly.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The Data

Let's start with highest of high-level data. The Energy Institute's Statistical Review of World Energy is a starting point for these discussions as it painstaking provides the data for the global and national state of energy production and consumption.

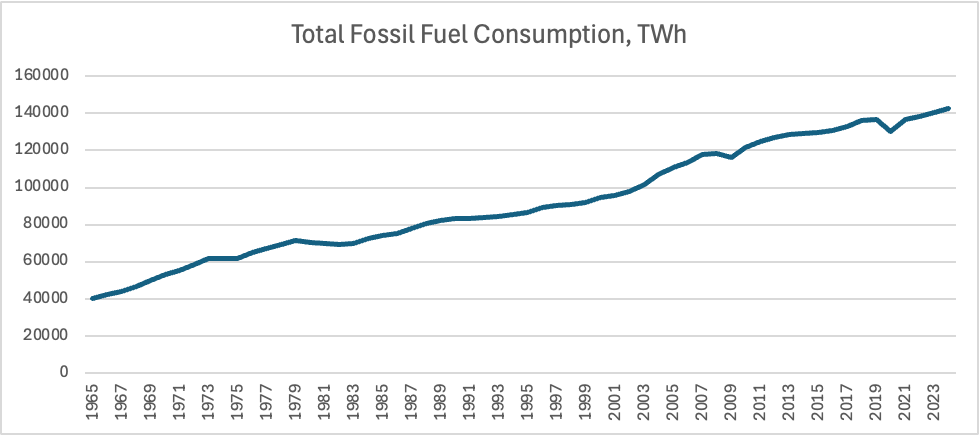

Often people start with just total amalgamated fossil fuels comsumption. From that high-level perspective, we see the steady, endless rise of fossil fuel consumption.

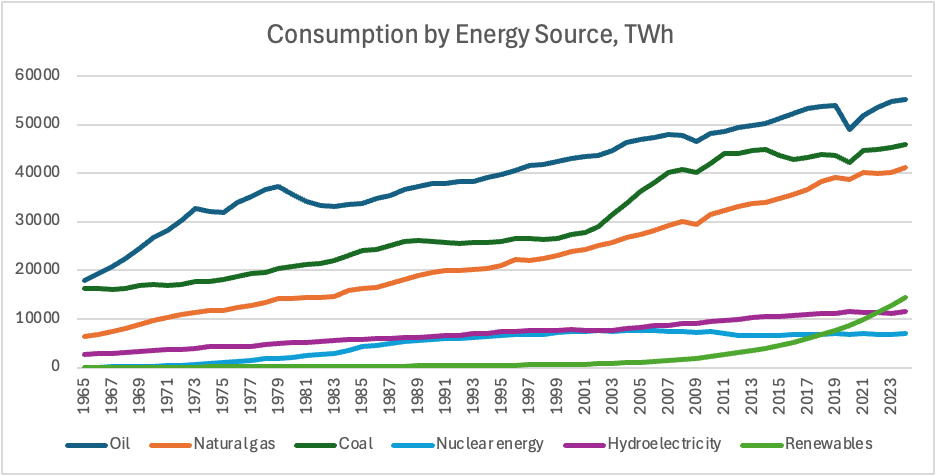

Looks pretty straightforward, right? With the exception of a couple blips and plateaus, total consumption of fossil fuel-based energy has continued to increase over time. But fossil fuels are exactly that, fuels, plural, and coal, oil, and gas each have their own dynamics within each segment.

They are also, notably, not the only source of energy we have.

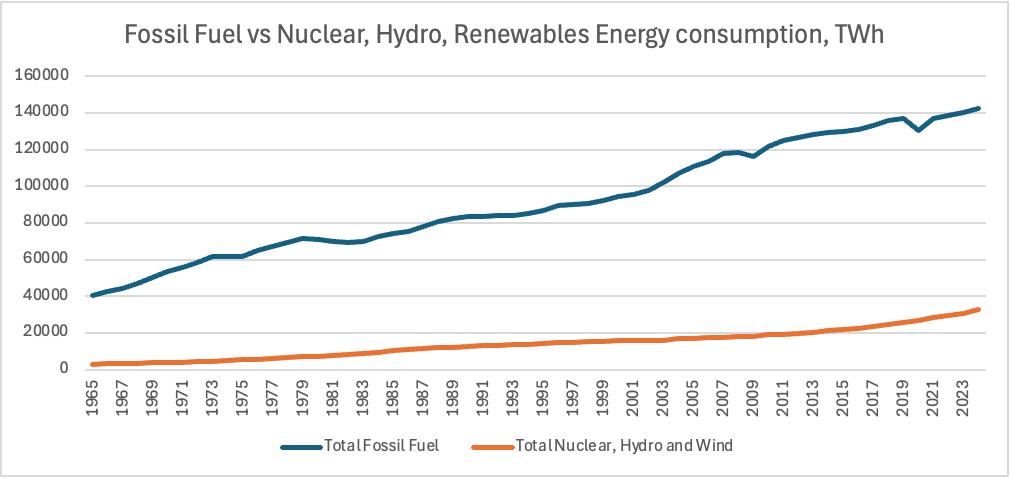

Adding the Energy Institute’s non-fossil fuel energy is a first helpful comparison. Clearly, fossil fuels dominate the energy mix. However, non-fossil energy consumption is clearly accelerating.

If you follow that light green line on the bottom — the one with that parabolic growth trajectory — that’s wind and solar, that’s $780 billion (USD) spent in 2025 alone. Bundling all fossil fuels together looks impressive, but it misses the more important trends at play. Some of the trees in this forest can’t — and mustn't — be missed.

Making Sense of the Data

The authors of the Statistical Review of World Energy, however, are not merely creating a data catalog. The review is an attempt to make sense of the dynamics of the global energy system and, in its raw, "by the numbers" approach, rolls up into key insights that they try to use to help people understand what's happening. Below are quotes from their insights section, with my emphasis added:

- Although wind and solar grew nearly nine times faster than total energy demand, fossil fuels also grew (just over 1%) in 2024.

- At 4%, electricity demand growth continued to outpace total energy demand growth, an indicator that the world’s energy system continues to electrify.

- Oil remains the largest source of energy, meeting 34% of total global demand in 2024. Although slowing, global demand increased by 0.7% to breach the 101 Mbbl/d level for the first time ever.

- [A]ll regions exhibited either a slowing down or a plateauing in oil demand in 2024. OECD demand remained flat at 45 Mbbl/d whilst non-OECD demand grew by 0.7 Mbbl/d.

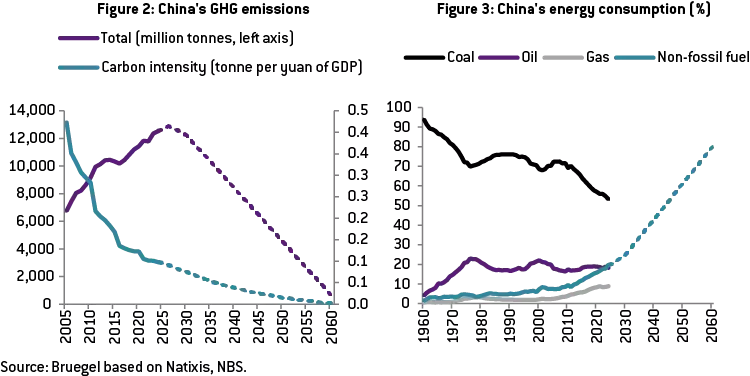

- China displayed signs of oil demand peaking in 2023 and registering a 1.2% drop in demand in 2024.

- Wind and solar met 53% of the global increase in [electricity] generation [in 2024]. Generation from renewables, including hydro, met 32% of global electricity supply [in 2023].

- Generation from wind and solar increased its share of total global generation from 13% to 15% in 2024. The past ten years have witnessed a fourfold increase in their combined output with wind broadly responsible for 55% and solar 45% of their joint output.

As they say in the opening paragraph of the summary, all of these factors contribute to an energy transition, and one that, as I agree, is increasingly disorderly.

Energy Security and the Transition

The Review has a special section this year on the use of renewable energy as a pathway to greater energy security. This is perhaps one of the most blindingly obvious aspects of the energy transition: if you’re a country that is dependent on the rollercoaster of commodity prices (i.e., oil and gas), it is in your best interest to get off the ride.

This is the premise of the substitution of fossil fuel imports for renewable energy that many countries in the global south are amidst.

As the Review notes:

Where the energy transition initially focused on tackling climate change, [geopolitical instabilities] have highlighted the need for resilient, decentralized, and clean energy systems. 2024 may well become seen as a beginning of a paradigm shift where the energy transition becomes increasingly associated with a need to deliver energy security through energy independence to protect countries from the types of shocks and uncertainty that such events bring.

There’s a strange brain worm that most older leaders in North America seem to have absorbed that energy security necessarily means people will default to fossil fuels. The Review and innumerable other analyses are clear: the trend is increasingly the reverse.

There’s a profound backwards-looking bias in the assumption that poorer countries will grow their wealth in the same way that today’s high-income countries did in the 20th century. Fossil fuels were the cheapest and most efficient way to do that in, say, 1960, but that is no longer the case.

To dismiss the dual rationale of building renewable energy (leaving aside climate change) on the basis of lower costs and commodity cycle avoidance is to fundamentally misunderstand our present energy environment.

But this is still incomplete on its own, there’s one other factor that is leading to this shift: China.

Electrotech as Geopolitics

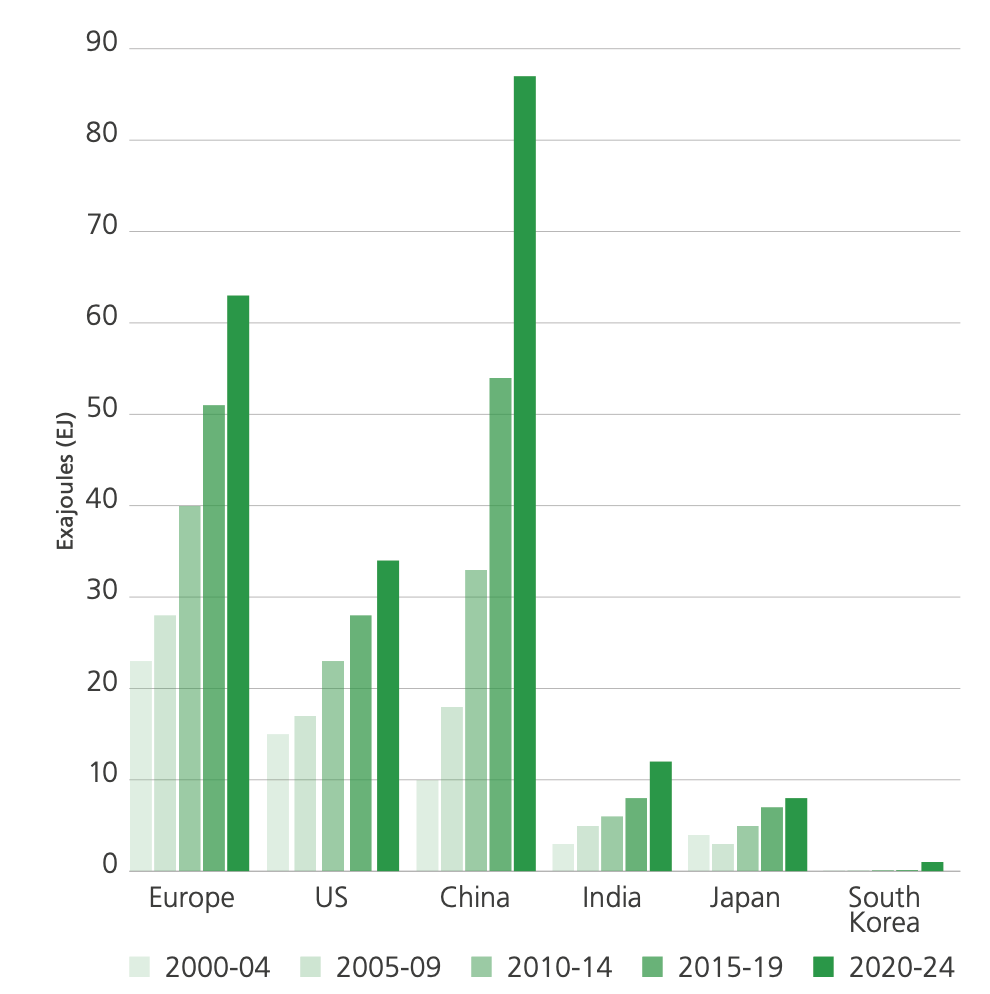

The Review is clear that China is on the forefront of using renewables to create domestic energy security:

A leading investor in renewable energy, China is at the forefront of realising such benefits. Whilst it is still heavily reliant on energy imports, they met around 25% of its total energy demand in 2024, renewables have helped it avoid importing around 87 EJ over the past five years, more than Europe’s total energy demand in 2024.

As many commentators are noting, China appears to be buying less and less gas, instead relying on domestic coal plants, which they can cycle on and off as they need, to insulate it from global commodity shocks, while continuing to build out more and more solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear.

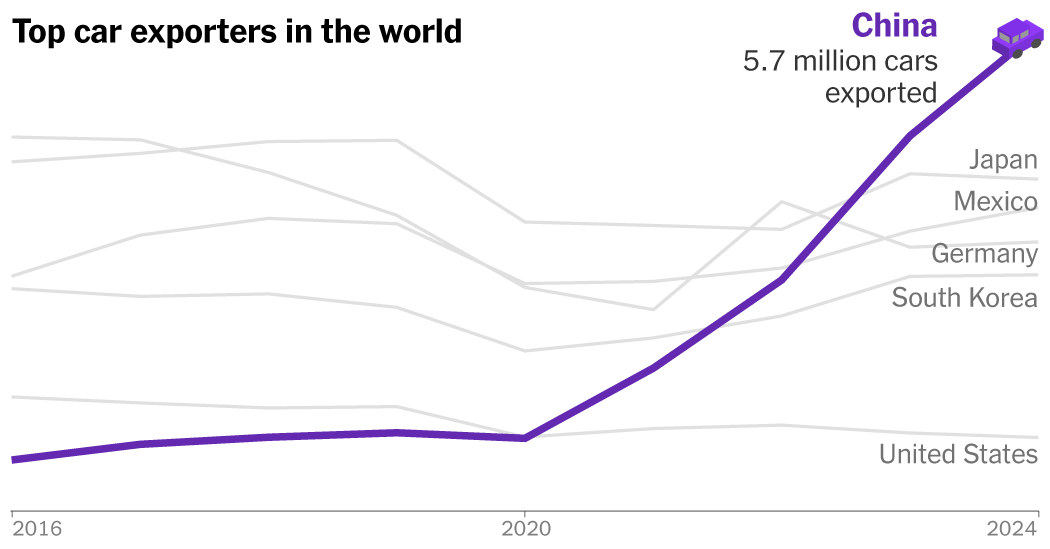

But that’s not all it’s doing. China is purposefully pursuing a project of geopolitical reorientation with its mind-bendingly low-priced renewable energy technology (“electrotech”) exports.

The Electrotech RevolutionDaan Walter

The Electrotech RevolutionDaan Walter

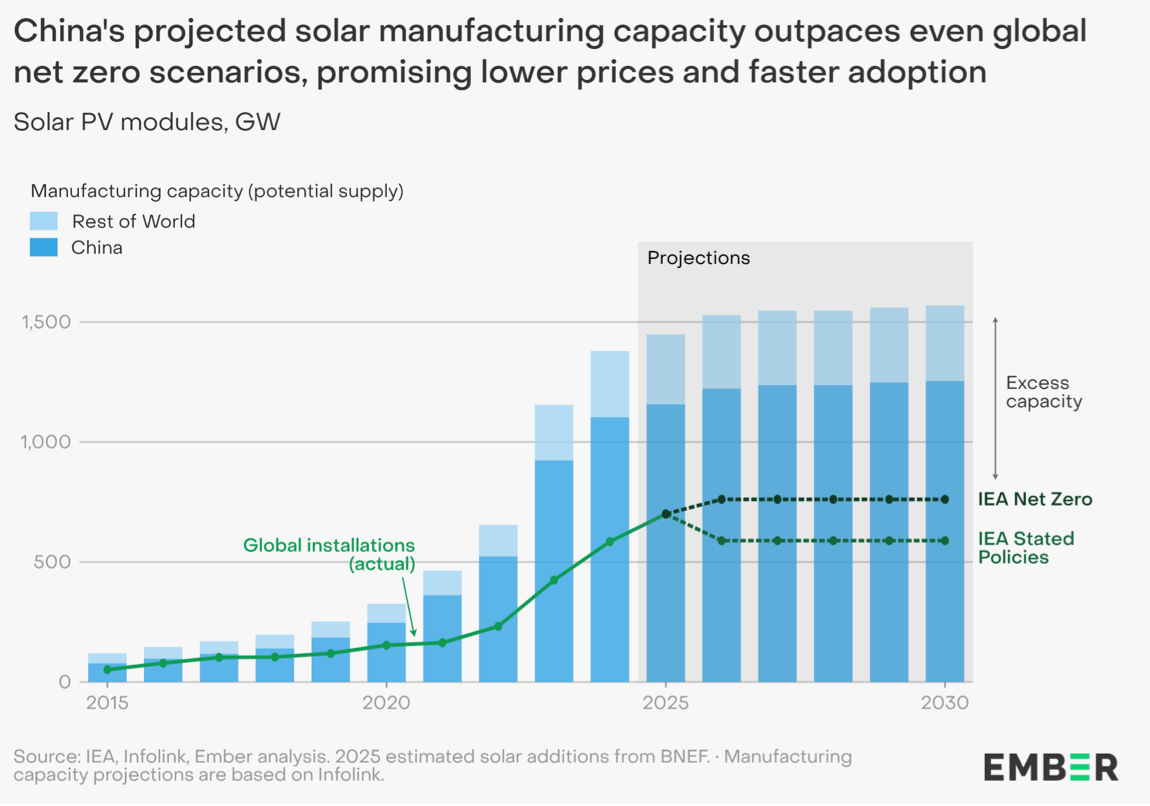

Ember’s recent China Energy Transition Review hits the scale and scope of this home with some numbers that shock and concern me:

- 75% of global clean energy patents come from China.

- 25% of emerging markets now outpace the United States in end-use electrification (with 63% of emerging markets now having more solar than the US), because of cheap Chinese imports.

- China is projected to have 65% more projected solar manufacturing capacity by 2030 than what the IEA predicts the world would need to meet the IEA’s Net Zero Roadmap (761 GW).

Ember and many other analysts are saying it very clearly: China intends to eat fossil fuel producers’ lunch through subsidized exports of their many electrotech offerings.

You can see this a little in the 2024 Guidance on the Vigorous Implementation of Renewable Energy Alternative Action (关于大力实施可再生能源替代行动的指导意见) planning document from the National Development and Reform Commission and other departments:

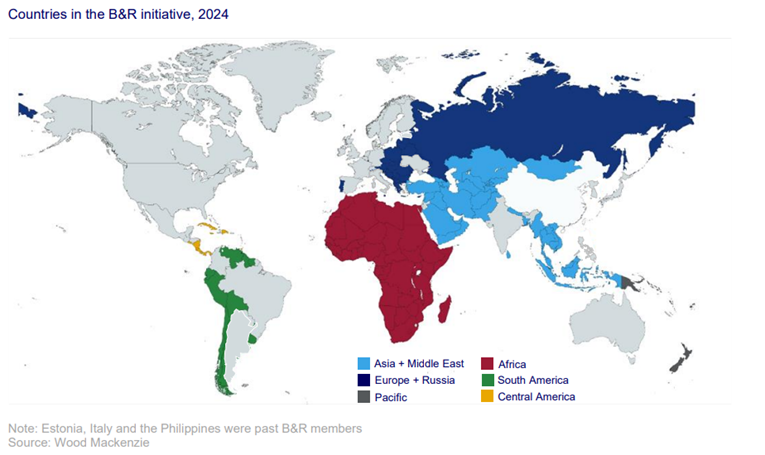

Deepen and promote international cooperation. Strengthen green energy cooperation with participating Belt and Road countries, deepen practical green energy cooperation, and promote the development of a number of green energy best practice projects. Establish a statistical analysis platform for international clean energy cooperation, and promote international cooperation in the research and development of advanced technologies and equipment for renewable energy applications in key sectors such as industry, transportation, construction, and agriculture and rural areas. Support exchanges on green certificates and green electricity with international organizations, and promote the internationalization of green certificates. Promote the Belt and Road Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan, and conduct joint research, exchanges, and training.

Despite headwinds from US and other countries’ tariffs and trade restrictions, Chinese exports continue at a breathtaking pace, navigating grueling domestic price battles and increasingly leveraging manufacturing located outside of Mainland China to be the delivery agents.

The New York TimesAgnes Chang and Keith Bradsher

The New York TimesAgnes Chang and Keith Bradsher

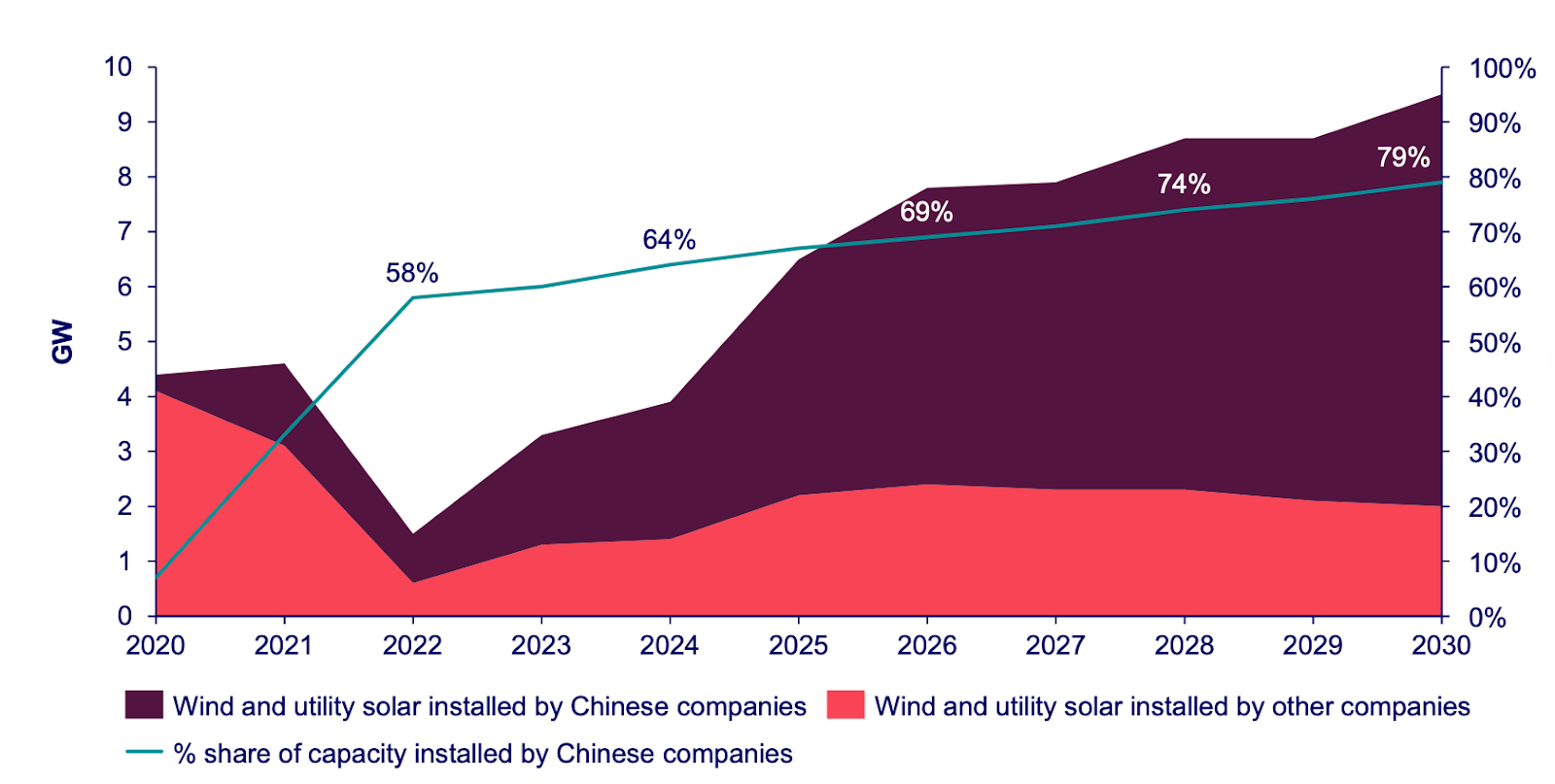

As Wood Mackenzie reported earlier this year, “Chinese companies installed 24 GW of power generation projects in Belt and Road [B&R] countries in 2024 — twice the capacity reached in 2023 — and the demand continues to grow.”

This huge investment is majority renewable, and, as reported by Boston University’s Global Development Policy Centre, it has included no new overseas coal development since 2021. China, according to Wood Mackenzie and others, will only increase its renewables export orientation to 2030 and the impacts of this are already being felt: Pakistan saw meteoric growth in its renewables in part because of these cheap panels.

Interestingly, pressures, such as the European Union’s EU’s Net Zero Industry Act targeting 40% domestic production by 2030, have only increased Chinese companies’ global expansion. The Belt and Road Initiative’s significant development of projects — i.e., noy just exporting individual units of technology — appears to be about building structural demand for their exports and shifting them into closer commercial relations with China.

The conclusion of this is simple: China wants to be the technology supplier of choice for one of the most fundamental components of any economy, energy. They’re orienting their entire economic strategy, from domestic manufacturing to global investment, to achieve this goal. Don’t let academic debates about how many new coal plants China built last year cloud your vision to the cold, hard reality of an economic strategy that directly threatens anyone who produces fossil fuels.

Addition, or Transition?

While sources like the Review and various IEA documents use the language of transition frequently and deliberately, there is a question often raised around what these investments all mean in light of the world’s seemingly rapacious demand for energy overall. Are we really amidst a transition, or are we just finding a new, cheap way to add to what we already have?

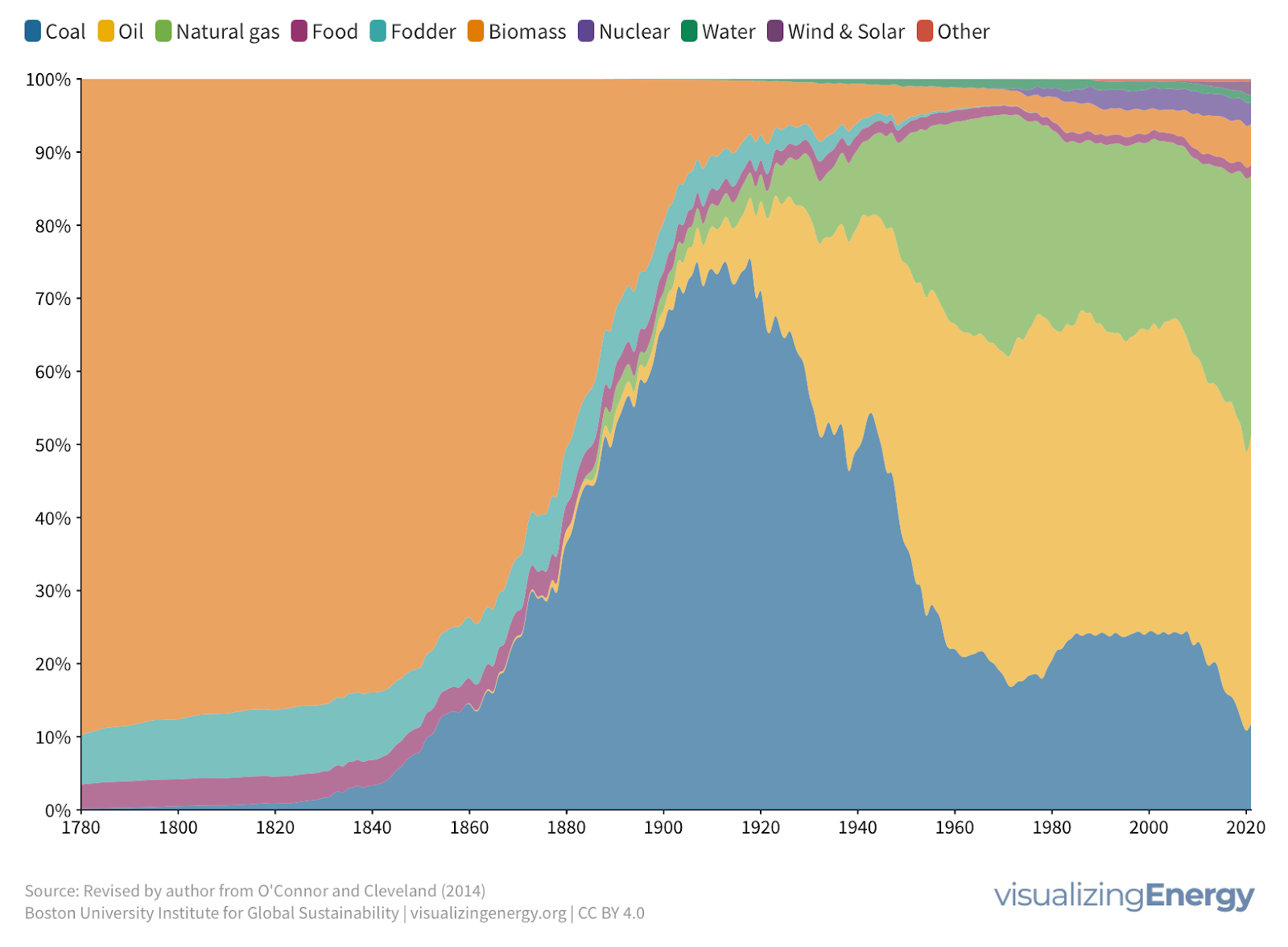

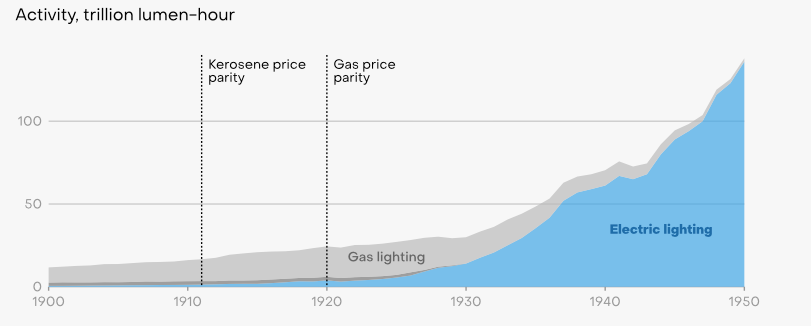

Kingsmill Bond on the wonderful Shift Key podcast addressed this question directly recently, calling out figures such as Vaclav Smil who are usually first in line to say (1) we’re only adding to what we have, and that (2) in fact transitions never really happen, we only ever just add more.

Bond disagrees and uses the example of fodder for horses, which used to actually be (believe it or not!) a primary source of energy, almost 10% of total energy in 1835.

I don’t know about you, but that sure looks like an energy transition to me.

Bond says, politely, bullshit.

If technology change is always about additions, he says, then:

“Where's your Nokia phone? Where's your horse? Where's your gas lighting?”

Going back to the fodder example, he says:

“There was such a decline in demand in the United States for fodder that the agricultural markets collapsed, and they began to turn to producing fuel alcohol for the new internal combustion vehicles as a way to prop up the agricultural markets and avoid a depression in the agricultural sector. And to this day, we continue to do the same thing with over 40% of our corn supply in the US going to ethanol production. It actually goes back much further than I even appreciated into the 1910’s when we first began to basically drive out the demand for fodder, which used to be enormous.”

But we’re not worried about horse fodder today. Canadians in particular are worried about the future demand for fossil fuels, which are an appreciable part of our economy.

And to this I say, with none of the glee you might have been told to expect from someone working on climate issues: be worried.

I am very, very worried.

Fossil fuels aren’t going away tomorrow. But the data show that we are amidst a global energy transition and outside of the United States, it’s not clear that that transition is slowing (even within, it's slowing, but doesn't seem to be dead yet).

If you’re a climate-motivated person, that transition is too slow for you. If you’re someone (or a country) dependent on fossil fuel wages or profits, then it might be starting to look a little too fast.

As from the start, lets look at the demadn for fossil fuels more closely:

Most data seem to point to the idea that oil demand, globally, is in a structural decline. The Statistical Review looked at the 2014-2024 consumption trajectories and found:

- Wealthy member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), representing 43% of global demand, shrank their oil demand by 0.1%.

- Non-OECD countries, representing 56% of global demand, increased their demand by 1.9%.

- Importantly, China, which consumes 16.2% of all oil in the world [and has been the vast majority of oil demand growth for the past two decades), may have now permanently peaked its oil consumption, seeing a 1.7% decline in 2024.

As I have written about previously, some Canadian shale oil producers may be able survive in markets as low as $25-30 a barrel, but if demand is truly entering structural decline, then we’re headed into a new and frightening era for the Canadian economy.

When it comes to gas, the story is better for producers. 1.8% increase in demand over the same decade, with every region except Europe and Latin America growing.

That same growth, importantly, exists within a global gas market about to experience a significant supply glut.

George Patrick Richard BensonGeorge Benson

George Patrick Richard BensonGeorge Benson

As Bloomberg reported this September (free summary here), the world is looking at a multi-year glut of gas starting in 2026, with new US, Qatari, and other supply coming online that will depress prices. This creates a tricky situation for Canadians and others looking to join the boom:

“Analysts told Bloomberg that while Europe will remain exposed to price volatility over the coming winter, a significant surplus of LNG is expected to emerge by the second half of 2026 and grow through 2027. BNP Paribas and Morgan Stanley forecast that prices in Europe and Asia could fall below $10 per million British thermal units by late 2026, and even as low as $8 in 2027.”

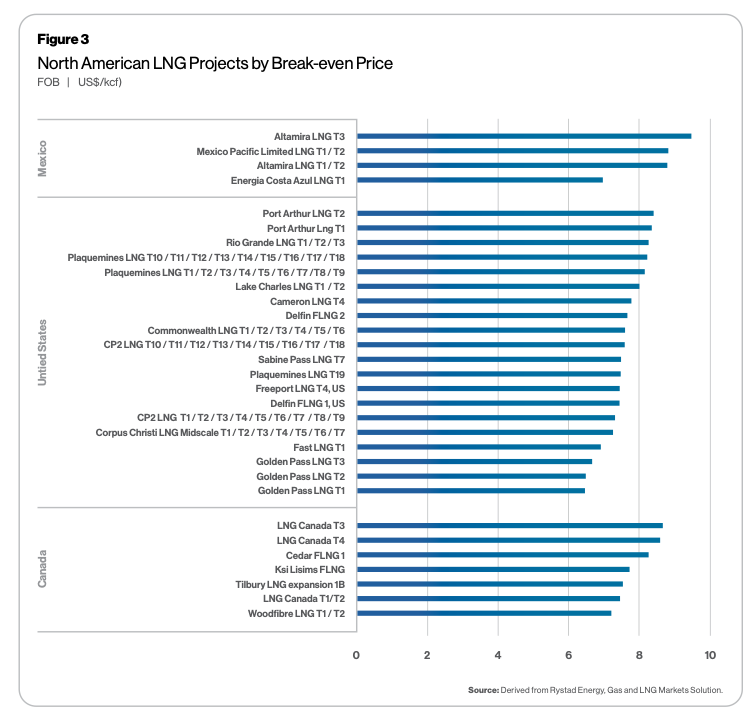

If we hit those prices, then we’re dangerously close to Canadian producers’ break-even prices (the BC-based project, LNG Canada Phase 1 needs $7.18~ MBTU and Phase 3 and 4’s of over $8 MBTU).

Contrast that with Qatar, one of the largest producers in the world:

“Qatar, whose gas already accesses markets Canada hopes to sell to, is set to increase its production capacity by 85% to 142 MTPA by 2030 and is able to break even at $6.75/MMBTU shipping to Asian markets. Qatar’s North Field Expansion project is set to be the world’s largest.”

The only thing I’ll say about coal prices is to raise a point that I see in more and more analyses: global coal demand increased after the 2022 energy crisis in surprising ways, but that may actually reflect some structural fragility for gas in many markets believed to have growth potential.

The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies noted this in 2023, writing:

A key uncertainty for gas is in the trilemma between coal versus gas versus renewables. Prior to the energy crisis, the consensus was that gas would benefit in any regions where coal was phased out and renewables, together with gas, gained market share. This was especially the expected situation in Asia. However, the energy crisis has seen coal make a comeback in 2022 and investment in coal continues in some Asian countries, and, if gas is seen as not being affordable, it may face an uphill struggle not to be crowded out by coal and renewables.”

China’s continued build out of coal plants that they keep turned off 50% of the time seems to support this contention.

We Need to Ask Different Questions

Canadians are used to seeing the energy transition through the lens of whether or not we should commit to reducing how much we use, and how much we produce, fossil fuel. Embedded in this question was an assumption about the resilience of global demand for these products and an idea of how competitive we would be with regard to that demand.

This assumption, and the questions that stem from it, no longer make sense.

We’re looking at a global market with a structural decline for oil and significant price competition in gas. This global market, North America conversations to the contrary, does still exist also within the constraints of climate change, both as a motivation to transition, and as an increasingly destructive force we must contend with.

Canada has not yet truly grappled with the reality of a global energy transition. Ensconsed away from radical price shifts, happily able to enjoy relative price security while making a buck on the swings elsewhere, we haven't really had to. But those times are changing. We're amidst a revolution in the cost, flexibility, and incentives (both national and consumer) of electrical technologies – this will fundamentally change the global economic order we live within. And we need a plan.

NoahpinionNoah Smith

NoahpinionNoah Smith

There will be hard trade-offs. If we'd prepared earlier, we could have been in a more Norway-like position to benefit from continued fossil fuel exctraction while ensuring our domestic industry and consumers were future-proofed for a different energy order. Now we will have to play catch-up.

As we do so, we need the questions we've been avoiding, like:

- In a world with price constraints for our most valuable exports, where can we quickly pivot to protect jobs and our overall trade balance as a country?

- How do we leverage continued profits from our commodity exports to invest in future-proofing our economy? (spoiler, I am not convinced it’s going to be in carbon capture for oil extraction)

- Where do we put increasingly limited public dollars to invest in our long-term economic security?

- What are the long-term implications for Canada and the provinces’ fiscal positions as these export opportunities shift?

- How do we ensure that everyday Canadians who work in these sectors get the support that they deserve?

There are answers to this. The work of the Transition Accelerator's Centre for Net Zero Industrial Policy is one that I watch, for example. They and many others think, and with which I agree, that Canada's sweet spot will include some mix of critical mineral mining and processing, development and management of clean electricity to power industry, and continued deepening of our software and services expertise in relavant growth sectors.

In subequent posts, I look forward to exploring more of those ideas. But for now: the energy transition is clearly happening, and we need a plan for how our country will navigate it.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.