Yesterday it was announced that Donald Trump has paused, for the moment, his his intention for the United States to move forward with its 25% tariff on Canadian goods. There are so many things that I want to say. I know I speak for so many Canadians when I say I feel a profound sense of betrayal. What Donald Trump and his administration have done so far, and what they may yet do, brings us to the precipice of economic devastation on both sides of the border. And for what? Incoherent ramblings about border security even he doesn't seem to fully believe.

Trump's actions also represent a meaningful end to – for all its many flaws – the past era of a rules-based international order.

As I sat watching Prime Minister Trudeau's press conference on Saturday, and the words of Premiers Eby, Ford, and Legault in the days that followed, I couldn't help but think back to the oil crisis of 1973.

It radically reshaped the global order from an initial series of seemingly small decisions in ways that may yet prove similar to now – but does it also offer lessons for us?

I think so.

In 1973, the top billboard hits were "Tie a Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree" by Tony Orlando and Dawn, "Bad, Bad Leroy Brown" by Jim Croce, and "Killing Me Softly With His Song" by Roberta Flack. It doesn't shock me that, in a decade that was already proving turbulent, some of its most popular songs are comfortably romantic and far-away from politics.

The year was turbulent from the start: the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland enter the European Economic Community on the first of the year; in May, Héctor José Cámpora becomes democratic president of the Argentine Republic ending almost a decade of military dictatorship that began in 1966. President Nixon, uneasily sworn into his second term on January 20th, makes noises about peace in North Vietnam, at the same time as Senate's investigation committee on Watergate is picking up steam.

By October 6, after increased posturing and still-nursed grievances from the 1967 war, Egypt and Syria launch a surprise attack on the Israeli-occupied Sinai Pinsula, kicking off the Yom Kippur War.

The next day, in a show of support, Iraq nationalized the assets of US oil companies Exxon and Mobil within the country, showing their support for their Arab countrymen in the war against Israel. They call for an oil export ban to the United States and other Israeli allies afterwards.

By October 9th, the Dutch government had put a nationwide ban on driving on Sundays to save gasoline during what was expected to be a worldwide oil and gas shortage.

By October 12th, both the United States and Soviet Union had sent aid to their respective client states in the Middle East. In response to aid to Israel, all Arab nations, then the world's largest oil producers by far, blockade oil exports to the US, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

Experiencing declining domestic oil output by 1969, the United States had become increasingly dependant in imports, with 83% coming from the Middle East, and the rest from Venezuela and Canada. The embargo was almost immediately devastating and it would take until March of 1974, after the US had negotiated the Israel pull-back from Sinai and Golan Heights for them to lift it.

Canada's Complicated Riches

In what feels bizarre anachronism in today's interconnected world, Ian Muller notes that,

At the onset of the oil embargo, confusion existed as to whether Canada was also an intended target. At this time, Canada did not have adequate embassies or consulates to determine if and why Canada was a blacklisted nation.

While in 1973, Arab oil made up 25% of Canadian imports, initial reaction in Ottawa appears to have been muted, and more focused on leaning into its international peacekeeping role to help bring this round of the Arab-Israeli conflict to a close.

In actuality, though, and in no small part due to American import needs (and significant control over the Alberta oil patch), it would have wide-ranging impacts on Canadian politics – some of which we still feel to this day.

While oil was certainly not the only reason it was doing so, Canada was already pursuing a "Third Option" strategy, to move away from America-centricity in its foreign and economic policy well before the crisis. Ottawa was not especially pleased with the intensity of the American ownership in the oil patch, with 70% of refined petroleum products manufactured and sold in Canada owned by foreign, and mostly US firms.

In addition to the economic conditions, there were also geological concerns – in both Canada and the US – about the accessible resources being sucked dry within a few decades. As available domestic production peaked and strained, even before the oil crisis got into full swing, in March of 1971, the Minister of Energy, Mines, and Resources declared that all Canadian exports would be licensed (and therefore subject to shutdown).

In September, Trudeau announced that there would be the development of a pipeline from the West to Quebec, where they planned to refine oil for domestic consumption. This was due to East and Central Canada's reliance on imported oil – fuel prices quickly doubled as fears around global supply shortages came home.

Again from Ian Muller:

Of immediate concern was the now widened gap between the frozen price of Canadian oil and the price of overseas oil delivered to the east coast prior to the embargo. Initially the Canadian government planned to counteract this differential with an increase in the export tax to $1.90 a barrel, an alternative to letting the Canadian price rise.

By November of 1973, Trudeau Senior began to get more aggressive in his energy policy, prioritizing domestic energy security and supply, announcing an emergency conservation program, including a form of petroleum rationing at the wholesale stage, as well as a new national Office of Energy Conservation. (Which I think might live on as the Office of Energy Efficiency in Natural Resources Canada).

By December, Trudeau came to Parliament with an eleven-point plan on how to deal with the oil crisis, navigating both the need for a supportive NDP vote for his minority government, and the material conditions of the crisis. The plan included:

- Establishing an Energy Supplies Allocation Board to make decisions about who got petroleum during shortages;

- Establishing a nationally-owned petroleum company, which eventually become Petro-Canada in 1976.

- An end to the "Ottawa Valley Line," which had previously separated Eastern and Western markets, and the creation of a pipeline to Montreal to further support domestic refinement.

- A continuing tax on exported oil, equal to the difference between the domestic price and an export price, with a promise to split the proceeds 50/50 with the oil-producing provinces.

And though Trudeau promised not to reduce exports to the US, as global prices rose and supplies became tighter, by 1974, his perspective had changed markedly. 115,00 barrels a day of Western Crude were diverted from the US to Central Canada by the fall of 1974, and the energy minister told the Americans it could fall by another 150,000 by July, 1975, and all oil exports could end entirely by 1982. The federal government was going to prioritize domestic (and in this case, Eastern) consumption above exports, it said.

The dismantling of the bifurcation of Canadian energy consumption – exports for the West, imports for the East – had wide-ranging consequences we still feel to this day.

Western alienation, long fed by Ontario and Quebec political and business interests' desire for low-cost Western resources, became a powerful political movement in its own right. This would reach its apogee in 1980 with the National Energy Program. In the broader North American context, the United States and Canada would sign the Transit Pipeline Treaty, within which both countries pledged to ensure generally unimpeded flows of hydro-carbons between one another.

The Government of Canada, also, much to Alberta's endless fury, also made significant investments in the oil patch. The first was in partnerships with Alberta and the private sector to create synthetic oil,leading to the Syncrude facility at Mildred Lake, Alberta. But later, they became more aggressive, and by 1976 had founded Petro-Canada to extract, refine, and sell oil and gas within the country.

Americans at the Gate

The interaction between Canadian sovereignty and US economic and strategic objectives here is certainly familiar. In the broader context, American interests in the Middle East drove unintended (global) consequences in terms of the oil embargo, and then, as Canada began to re-asses its own strategic priorities, frustrations increased.

American officials at first became frustrated at the domestic price differential between US and Canadian oil, and then increasingly concerned as refineries indicated that their specialization around Canada's sour crude left them with no effective replacement. More broadly, some were worried that this signalled a long-term decline in oil availability for American industry and that it would hurt overall economic output.

Whether through his own particular charm and effectiveness, or simply American self-interest, then-Minister of Energy, Mines, and Resources, Donald Macdonald, was generally able to convince the US that petroleum self-sufficiency was a goal that both nations shared and which could be delivered amicably. It was this vision that would enable the later treaties and increasing energy cooperation between Canada and the US that, more or less, have brought us to today.

Navigating in the Here and Now

Importantly, what I briefly summarize here doesn't touch on the political fights that would come from the National Energy Program in 1980. The oil crisis brought political and economic frustrations about Canadian energy policy into broad daylight, but the political crisis of 1980 wasn't a guaranteed thing at this point, though its foundations were certainly laid.

That's why, however, it feels important to bring us back to this moment: in many ways it helped get us on the road we've arrived at, and both the similarities and differences from it are instructive.

Most importantly, the biggest difference between then and now is the incredible growth in American oil production. For all of Donald Trump's talk of "drill baby drill," Obama, himself, and Biden all oversaw a dramatic expansion of US oil production, now the highest in the world.

Let's be clear: there would still be massive economic implications associated with either less, or eventually no, Canadian oil into the US. They still operates many specialized facilities that turn the more sulphurous Canadian oil into "sweet crude" that's ready for global export (at a generous discount, I should add), but American oil production effectively doubled under Biden and with over 6,000 unused drilling permits (and many more set to be approved), this number could increase much more.

Importantly, what this means is that, while Canadian oil is indeed a massive export to the US, we are not in the 1970s anymore; one of our most strategic resources is not needed the way it used to be and need to be conscious of that and not over-leverage ourselves.

Where the moment is similar, and where Canada may yet be able to replicate its past success with syncrude, is the opportunity to co-invest in infrastructure and innovation. There had been a major facility under development in Alberta to produce synthetic crude, but as the energy crisis worsened, the Atlantic Richfield Company had decided to leave the project at the end of 1974. With the project in crisis, the "Winnipeg Agreement" was eventually signed, with

a successful effort to replace with government money the project funding lost through the departure of Atlantic Richfield. Ottawa, Alberta and Ontario agreed to split the financing difference. Alberta also agreed to construct a pipeline and a power plant.

The investment in snythetic crude proved durable and has been a massive enabler to the incredible expansion of the Albertan oil sector since the 1970s. All on the basis of a joint investment between the Governments of Canada, Alberta, Ontario, and a private sector consortium.

There are many talks of similar processes of investment today, with government and private money mingling together, but the areas this time will be different. Danielle Smith's call for us to double-down on the hydrocarbon economy feels right out of the 1970s, instead of where we might compete in the twenty-first century. Nuclear technology (both fission and fusion) for the power sector, and possibly particular artificial intelligence plays might be the strongest bets from an innovation perspective, while further deploying clean electricity across the country would be a more hum-drum no-brainer (as I wrote about toward the end of my three-part series on energy in BC).

George Patrick Richard BensonGeorge Benson

George Patrick Richard BensonGeorge Benson

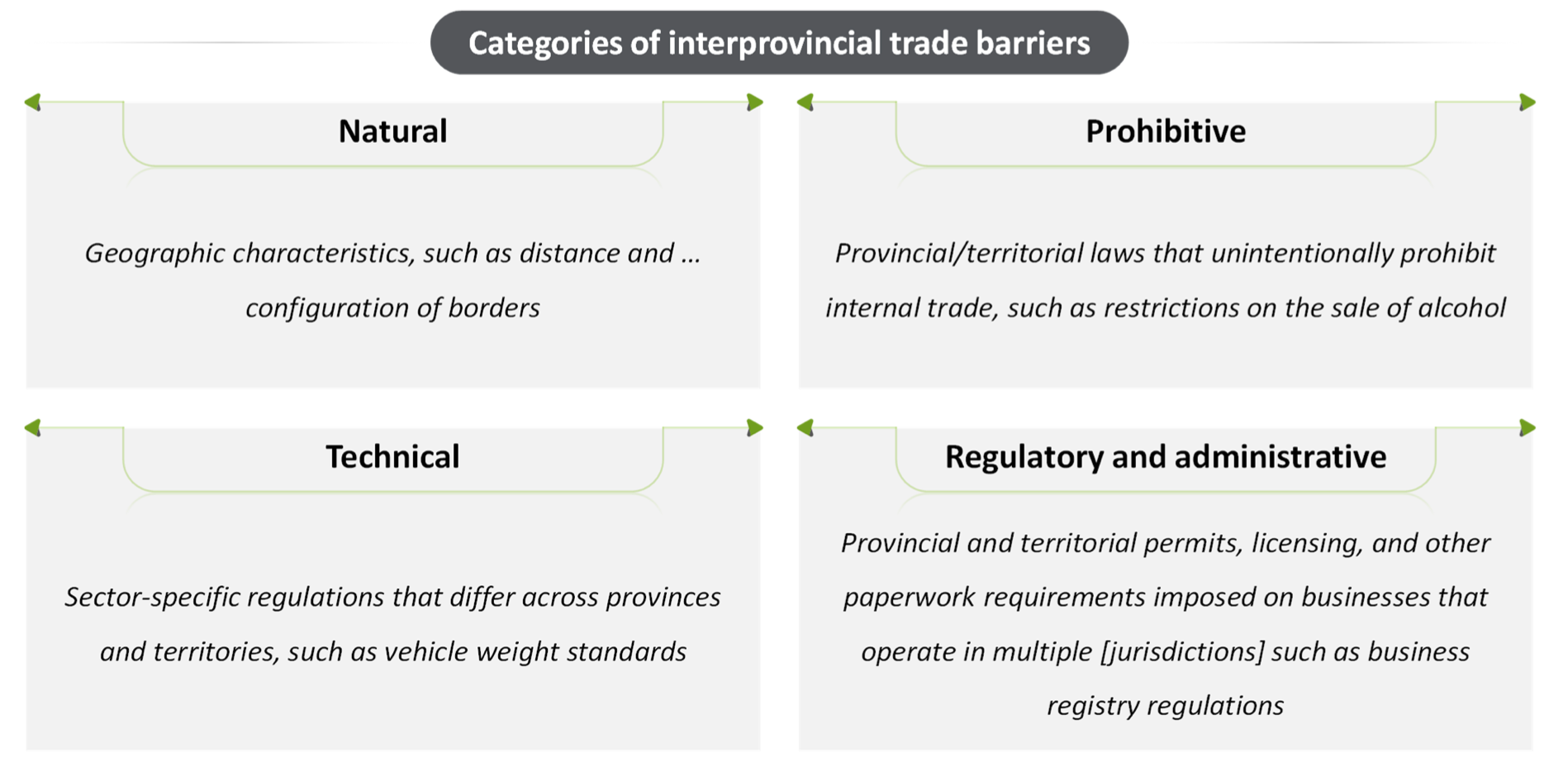

Another area of action that certainly we learned what not to do from the 1970s is inter-provincial trade. My favourite report on this, in no small part because of its cheeky title, is Tear Down These Walls, by the Senate of Canada. Almost a decade old, it is not reflective of some of the major changes that came through with the Canadian Free Trade Agreement (CFTA) in 2017, but many still argue there is further to go, as Business Council of BC CEO Laura Jones did in a recent interview.

The IMF and others have argued that Canada has a lot to do to work through these internal barriers. As the Canadian Chamber of Commerce writes:

While it provides some progressive relief measures on specific areas such as procurement, much of the 300-page document is dedicated to exemptions, creating opt-out measures on many key files that continue to pose significant issues at the sub-national level. Moreover, there exist many persistent regulatory concerns that fall outside of the CFTA’s intended purview.

An example identified by Deloitte from 2021 is instructive:

Certain truck configurations (mostly oversized and overweight) must be driven at night in British Columbia but only during the day in neighbouring Alberta, leaving just a small window of time to cross provincial barriers.

While I and many others have concerns around any "race to the bottom" in terms of standards for health and safety, among other things, I don't think that should stop us for fighting for a more interconnected country.

As an IMF team wrote in 2019, including noted Canadian economist Trevor Tombe:

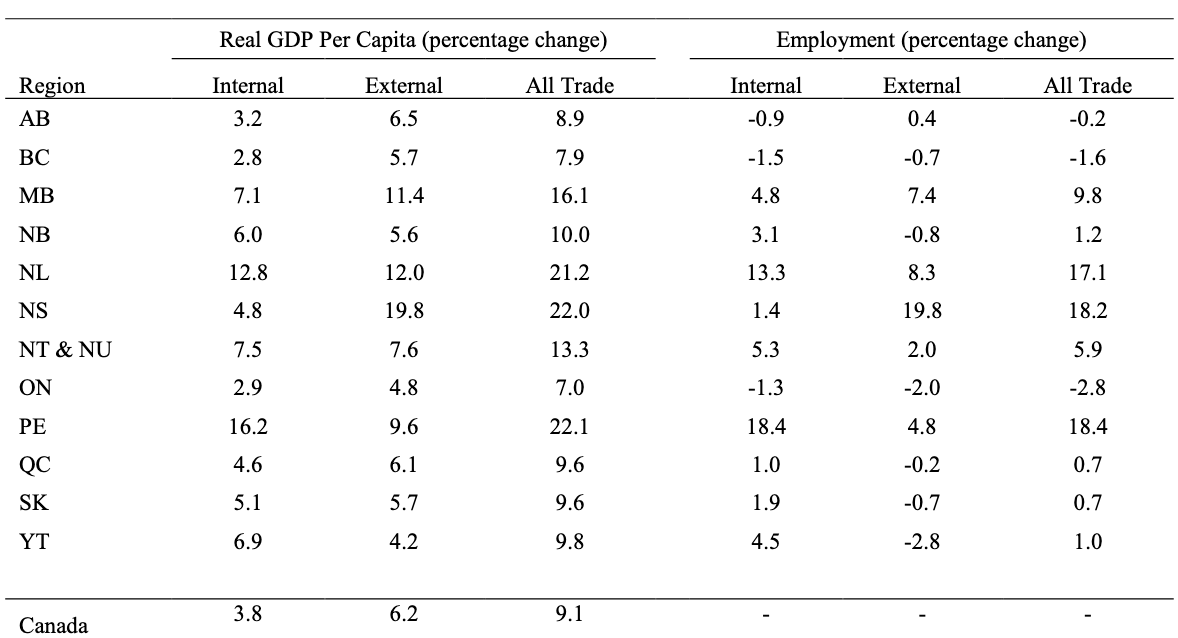

Removing non-geographic internal trade costs increases trade volumes as a share of GDP by roughly 15 percentage points [...and] Real GDP per capita would increase by 3.8 percent nationally, with gains as large as 16 percent in Prince Edward Island.

The agreement in 2017 adopted some of the Senate's recommendations, including moving to a "negative list" approach, where you have to pull something out to protect it, rather than go line-by-line on everything. But there are still further areas that could be streamlined, with significant benefits to Canadian consumers.

The last thing that I think the 1970s crisis really began to unearth is the challenges within the Canadian "fiscal federation." Canada is a strange country in how revenue and taxes are spread out. Two levels of income tax, different provincial corporate tax rates, and a flurry of other taxes and fees that often levied in counter-productive ways. To be clear: taxes are good and important, but we want them too be effective, too.

UBC economist Kevin Milligan has one of my favourite ways of framing this back in a lecture he gave in 2017. As he helpfully contextualizes: non-federal expenditures (e.g., healthcare, schools, etc.) made up almost 80% of all spending in 2016, the highest in the OECD and almost 50% higher than the average. Also, worryingly, are the projections for federal and provincial debt.

If you look at the "Long-term Projections" tab on this debt simulator from Finances of the Nation, you can see that currently we are on a trajectory, relatively unchanged from Milligan's work almost a decade ago, for the total provincial debt to get to 90% of Canada's GDP by 2048. When you look at individual provinces, this becomes even more dire – especially when you include often sidelined unfunded liabilities, like Alberta's at least $60-billion worth of.clean-up costs for orphaned and abandoned oil wells.

The long-term prognosis for Canada's ability to pay for services and service its debt doesn't look good. Milligan's solutions, which I am inclined to agree with at a general level, cover a dew dimensions:

We could increase the existing Canada Health Transfer substantially to fund provincial health spending needs. This would require a sharp increase in federal taxation over the next two decades. The federal government, with its easier capacity to tax mobile personal and corporate income might be better placed to raise extra revenue fairly and efficiently.

More boldly, he recommends we "flip he table" on the current breakdown of federal and provincial taxes. The biggest and boldest idea here would be for the feds to give up a portion (4 points in his original estimate) of GST to the provinces, in return for the Government of Canada to manage all corporate taxes which would, in turn, largely go back to the provinces in terms of federal health transfers.

The elegance of Milligan's solution appeals to me, but I think there are other things we have to consider, too: Tobin taxes on particular niche financial transactions, income tax changes, and other ideas that things like the Alternative Federal Budget grapple with.

Bigger-picture than even this will be suggestions of Canada joining the European Union, or forming some sort of common market with the UK, Australia, and New Zealand. These ideas are so transformative as to boggle the mind, and while I remain unconvinced that they have the political will to take shape at present, we do indeed live in strange times.

The 1970s heralded in a new era of cooperation between the United States and Canada, with energy near the centre, but hardly the only aspect of a deepening relationship. Donald Trump's words and deeds in the next few years will do much to damage that relationship, unwinding half a century of integration in fits in starts. Canadians didn't do everything right in the oil crisis – Western alienation is proof enough of that – but there was one thing pretty much everyone agreed on then that we need to keep in mind now: a crisis is a hell of a thing to waste.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.