Since 2020, Nat Bullard has published "the" deck. From its origin at Bloomberg New Energy Finance (NEF) as the executive factbook, to its new, more straightforward existence as the "annual presentation" a unique and important centrality.

For those of us who work in climate and energy, its release is one of those big moments in the year, right up there with the International Energy Agency (IEA)'s World Energy Outlook, the Statistical Review of World Energy, the Lazard study on the levelized cost of energy, and the various alphabet soup of government agencies around the world that issue their own versions of the same.

For those of us trying to truly understand just what is happening in our changing global energy system (and, by extension, how it affects our changing climate), Bullard's meta-synthesis is both a unique and profoundly useful read.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

As I always do, I read his 2025 presentation front to back last weekend, but this time I pulled out ten of the slides that stood out to me the most, with a little commentary for each.

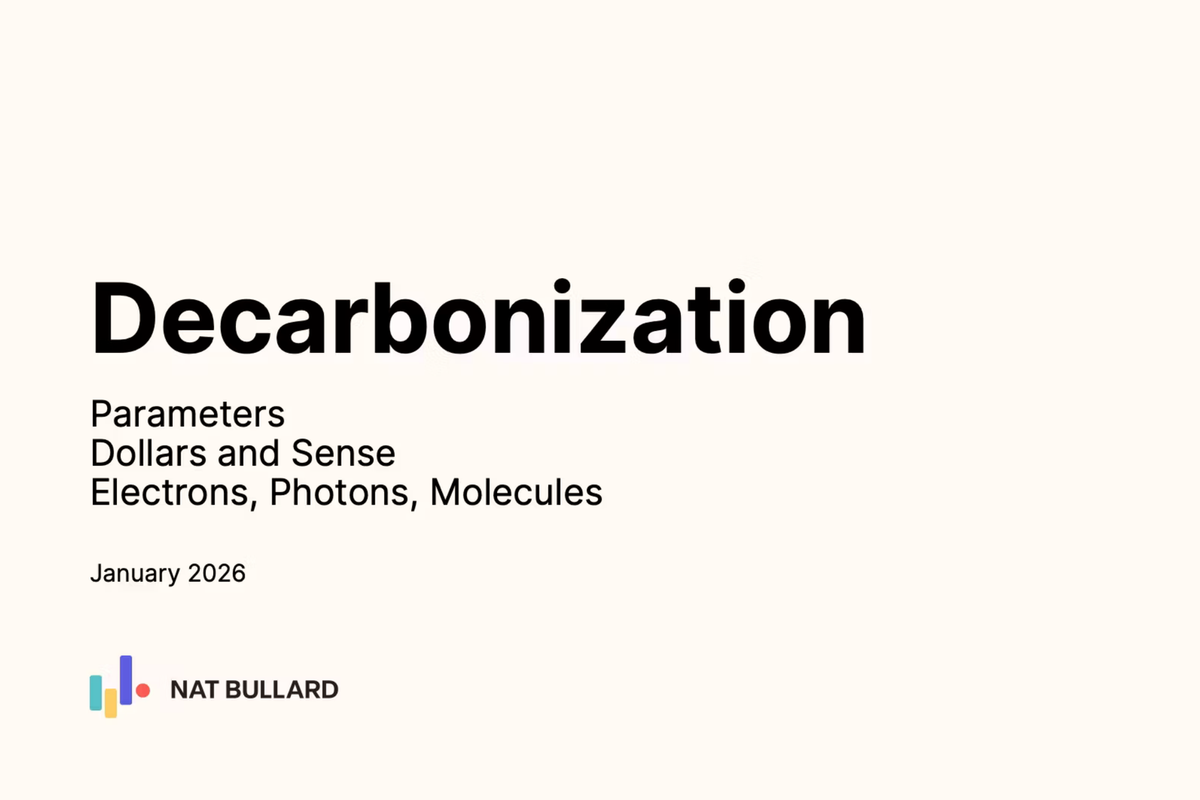

China is building fewer buildings, and the rest of us probably won't make up the difference.

Why is it interesting?

Cement production and use is one of the world's largest sources of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and also a massive energy user.

This downward in cement demand is actually a trend I have wanted to write a piece on for some time after reading the World Cement Association (WCA)'s 2024 Long Term Forecast for Cement and Clinker Demand. Bullard's graph here only runs to 2025, but as the whitepaper said at the time: "global cement demand in 2050 is likely to be much lower than current forecasts, around 3 billion tonnes per annum." As you can see, in 2021, globally we broke 4 billion tonnes per annum, but have been trending down since then.

What does it mean?

As both WCA and Bullard note, the single biggest reason is China. Despite a truly incredible amount of construction over the past two and a half decades, things are now slowing somewhat and this will modulate China's cement consumption downward.

This will mean they slip from 48% of global demand in 2024 to 32% in 2035. And while emerging markets in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia could grow fom 18% to 28% in 2035, those gains are still not enough to make up for the Chinese decline and flat demand in wealthy countries.

The other aspect is decarbonization. The growing demand for materials with lower "embodied carbon," the WCA argues, will drive focus on efficiency both in processes related to the production of cement and the ways in which it is used. They sound the alarm against carbon capture and storage (CCS) which they call "the worst option," but one they are somewhat beholden true as the only way of truly getting to net zero for the moment.

Unmentioned is the global sand crisis, though a cursory search suggests that that hasn't (yet?) impacted prices.

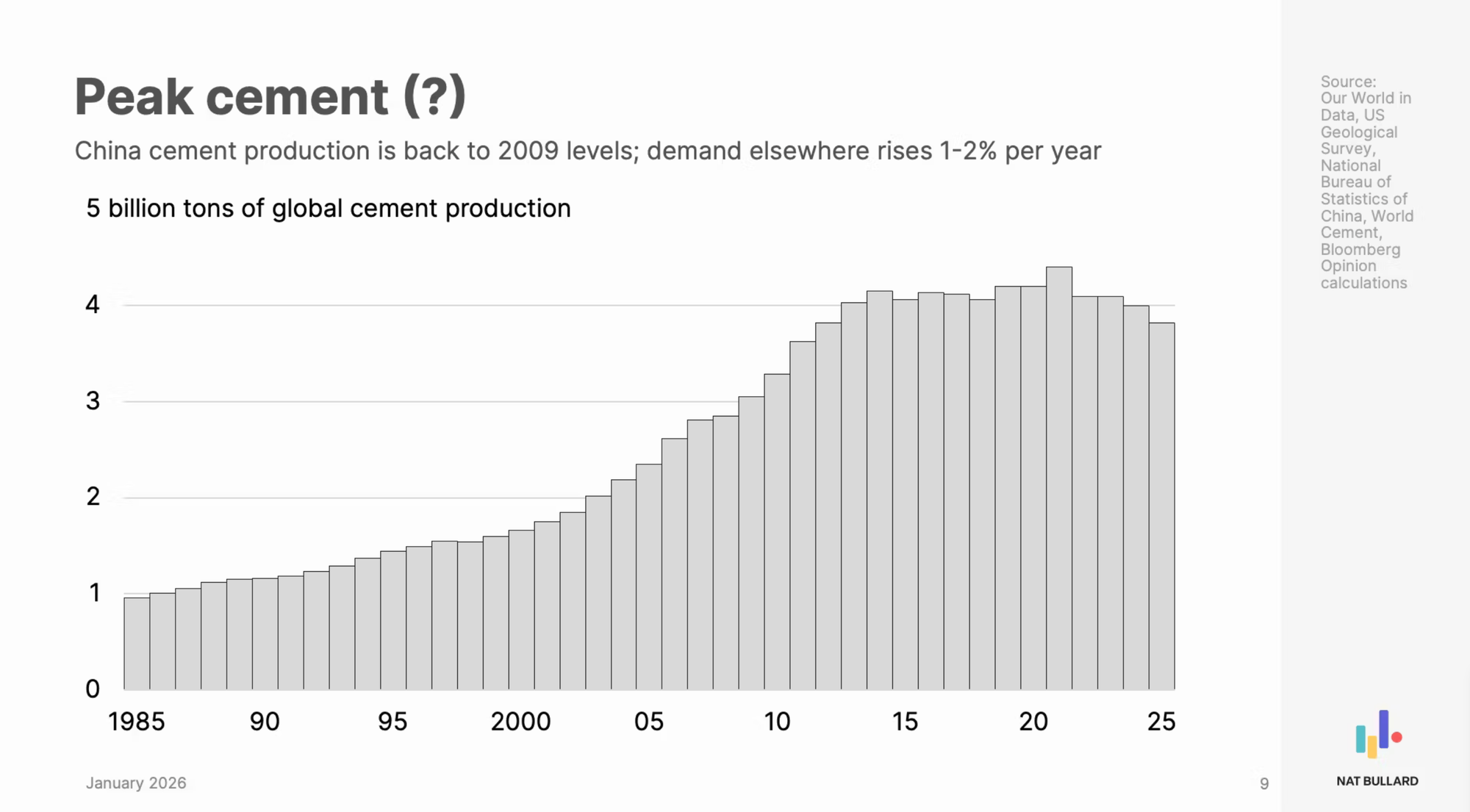

Land use disruptions are down, but so are carbon sinks.

Why is it interesting?

Land use changes – mostly cutting down trees, but other things, too – are a massive and often under-focused factor in global climate change. They drive emissions up in the short term by causing carbon to be released when plant matter dies or soil is disturbed, and they cause long-term effects by reducing the available carbon sinks to suck up future emissions. Land use changes have historically been a massive source of both carbon emissions and biodiversity losses.

Bullard here highlights data from the Global Carbon Project and the gargantuan carbon budget paper by Fredlingstein another 20 authors that make up the et al.

What does it mean?

While global emissions from land use change remain high, according to the Global Carbon Project, they have decreased since their peak in the late 1990s. This is thankfully due to some success: we've cut down significantly on the deforestation, particularly in South America. We've also done a lot of afforestation, with huge forrests (0.9 gigatonnes worth) planted in China, the US, and the European Union, offsetting almost the equivalent of Japan's annual emissions (1.1 gigatonnes).

The downside, however, is also that our land-based biomatter is also absorbing less carbon than ever before. The paper that Bullard cites says that "the effect of climate change has reduced land and ocean [carbon] sinks," the latter by an estimated 23%, over the past decade. With lower effectiveness, there is simply less carbon stored when a forest is cut down or land is changed.

It hits home that we have made progress, but like all things in climate change, systems are dynamic and non-linear.

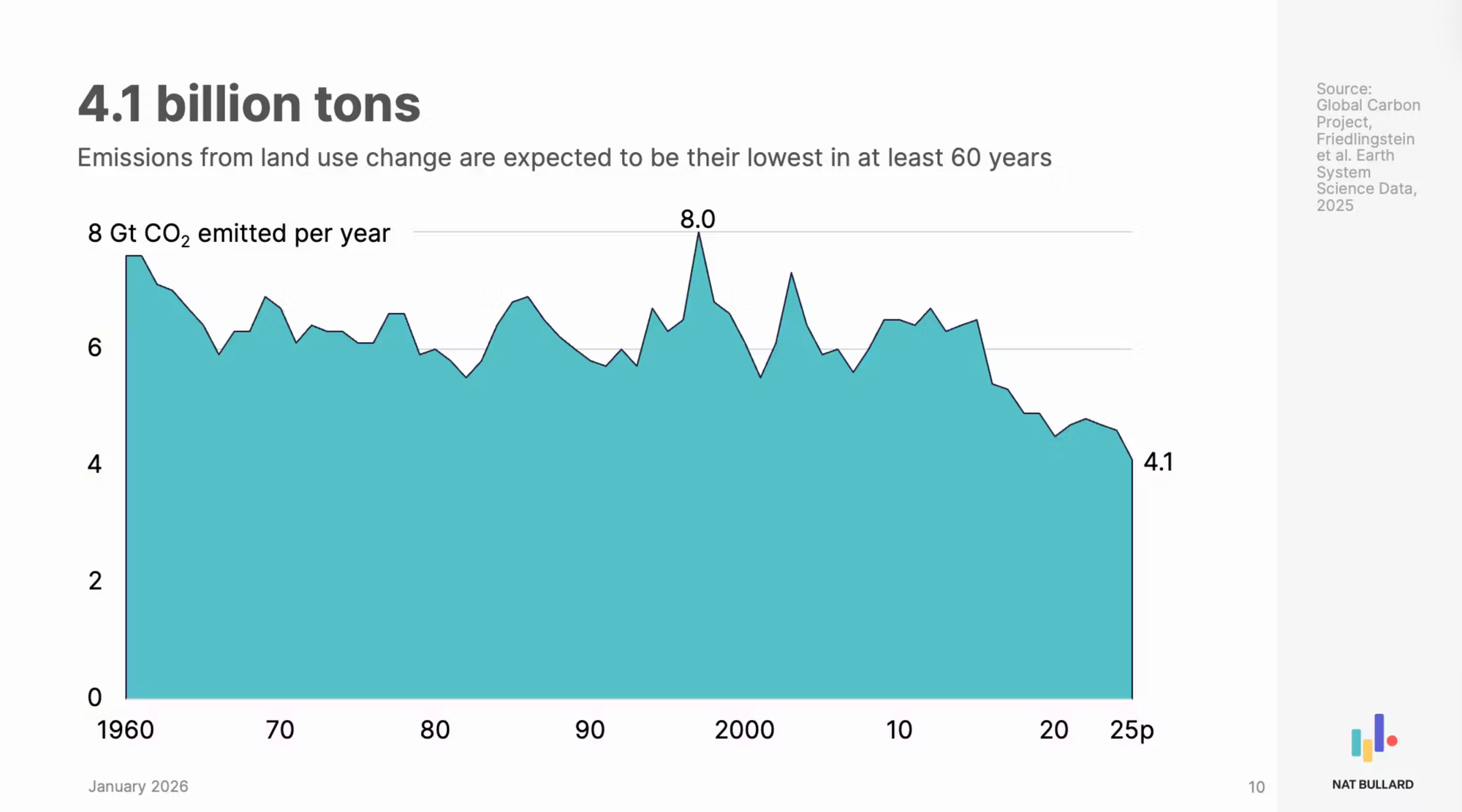

Africans spend a lot of money on fuel. They probably don't want to.

Why is it interesting?

Much ink (including mine) has been spilled on the nature of future global fossil fuel demand. For petro exporters, both the potentiality (and hope) of ever-hungrier, ever-wealthier countries in the global south is a boon and a lifeline as wealthy countries' fossil fuel use continues to decline.

Africa, where electricity use has doubled since 2000, is hungry for energy. More broadly, 74% of the global population lives in a state that's a net fossil fuel importer. But as Bullard suggests, the value of these energy imports is a double-edged sword. When one or two commodities represents 1/4 of all of your imports, you're going to be motivated to seek substitutes.

What does it mean?

Bullard here is pointing to a vulnerability that fossil fuel producers face: the more successful they are – the more valuable their exports – the more motivated their customers are to reduce their consumption.

Embers lays out this case in stark terms:

You could theoretically spend $100 million to import the same amount of energy in either gas or solar panels, but the solar panels are a one-off cost, and then save you $100 million a year thereafter. Over a 30-year lifespan, you could save as much as $3 billion.

Solar panels are only going to get cheaper as time goes on, though. These cost differentials are still only going to get worse for fossil fuel producers – and more favourable for renewables. Africans will probably buy a lot more.

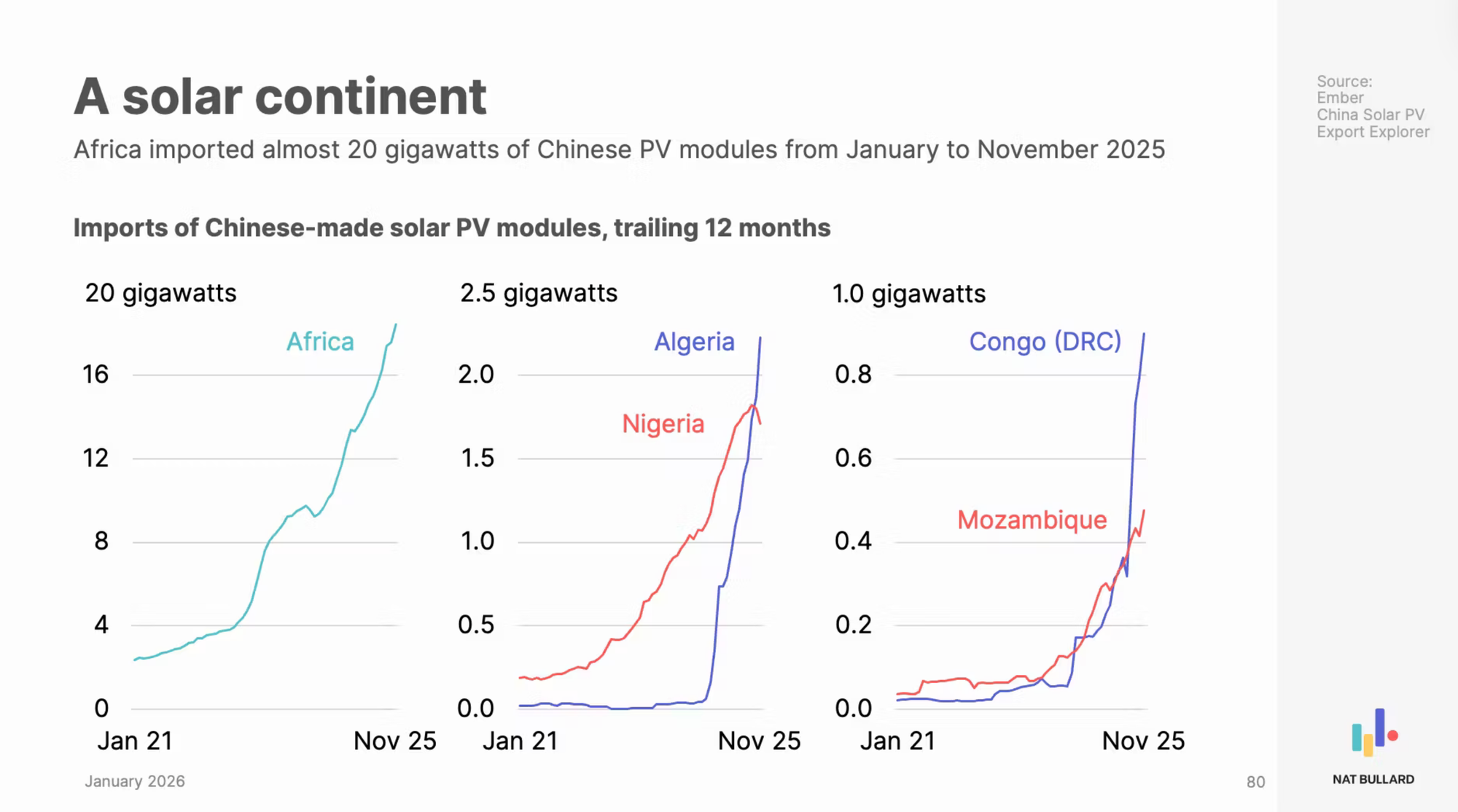

Africans also really like solar.

Why is it interesting?

As Bullard shows above, Africans – despite having massive fuel reserves – import a lot of costly energy. Notably, they're still mostly domestic consumers, but in dollar-value terms, it's a significant drain on their economy.

Also: African electricity use has increased over 100% in the past twenty years and will continue to grow significantly. Particularly as two out of every five Africans (600 million people) are without electricity and traditional large-scale finance is failing to deploy the kind of small-scale energy that disparate, low-income consumers there are looking for.

What does it mean?

The United States (and parts of Canada) is pursuing an IBM-like strategy, poo-pooing "cute" wind and solar while market-hungry China builds a Microsoft-like new business model that completely changes the game. As I said above, every imported solar panel into the Global South is a one-time cost for them, and a permament stopper in demand for fossil fuels, particularly as the purchase costs go down for solar as demand increases.

This chart appears to also take into account something that the African Solar Industry Assoiciation (AFSIA) has also acknowledged: counting solar means going beyond utility-scale deployments. AFSIA notes that when including imports of (you guessed it, Chinese panels) "we manage to obtain a very different picture of solar in Africathan what has been portrayed in the past." State numbers show 23.4 GW of operational projects, but Chinese export data indicate.that 58.1 GW have been exported to African nations since 2017."

This means that solar penetration in Africa could be as high as 2.75x higher than previously thought.

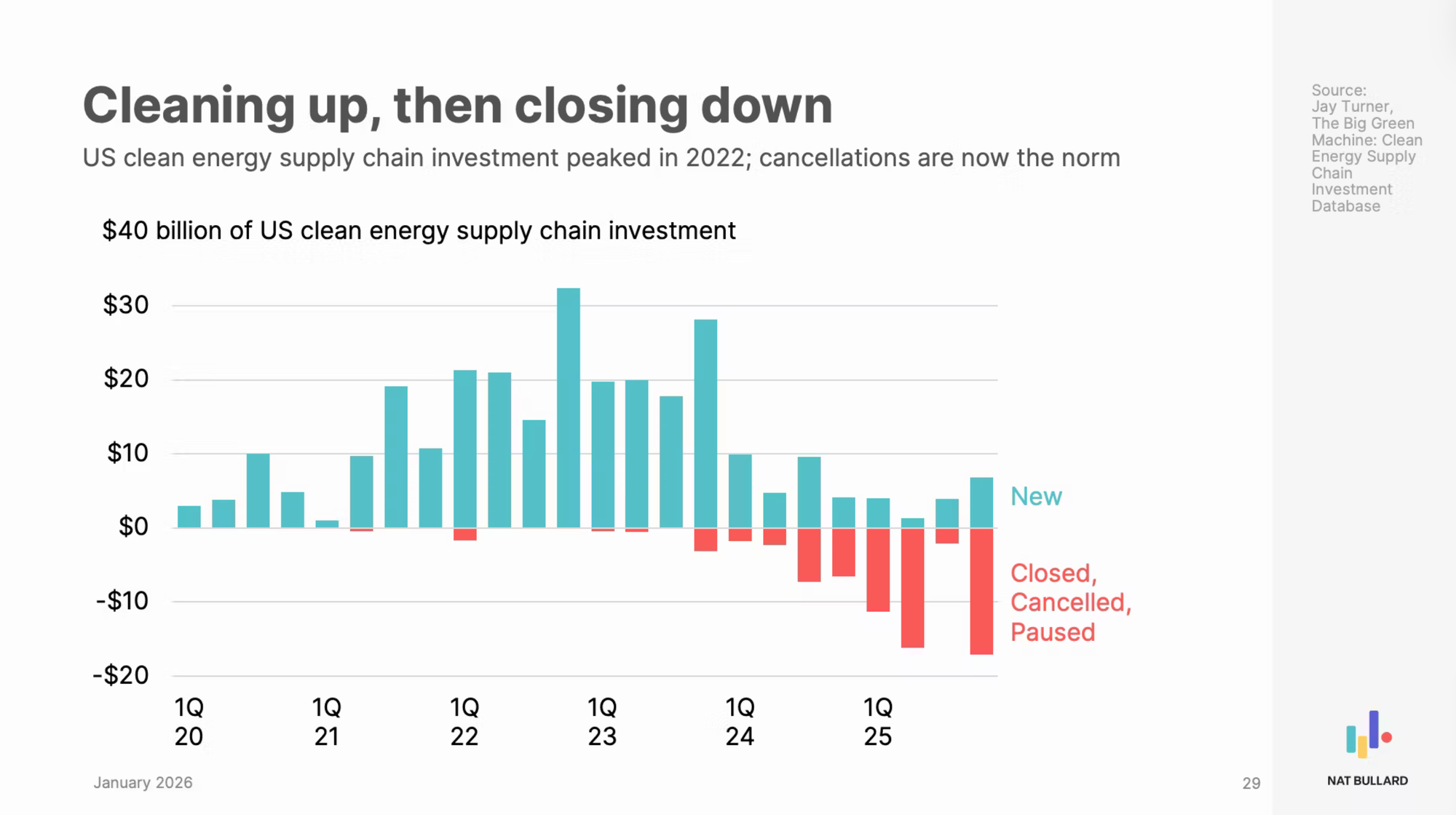

A new era of American technological dependence?

Why is this interesting?

For all of its flaws, the Inflation Reduction Act catalysed hundreds of billions in new investment throughout the United States, especially in the clean energy supply chain. While it's true that the Trump Administration's malicious stance towards the clean energy sector has proven catastrophic, Bullard's slides here show that there were headwinds by the first quater of 2024.

By Q3 of 2025, the Clean Energy Investment Monitor reported year-over-year declines of 56% in new industrial decarbonization projects, 26% in manufacturing, and 5% in consumer distributed energy technolgies. There were gains, too, but the overall picture is not rosy.

What does it mean?

The United States continues to cede manufacturing leadership on clean energy to China and, to a lesser extent, the Europeans and other manufacturers. EV's appear to be the most cataclysmic, presumably because of legacy automakers utter disinterest in the technology. The Investment Monitor reported a 15% dip in investment between Q2 ane Q3 of 2025, and a 30% year-over-year reduction for Q3.

While Americans continue to make batteries, solar panels, and other technologies, the picture from the IEA and others is one of utter dominance by the Chinese. Unless you're buying hydrogen widgets (or maybe heat pumps), your cheapest, and maybe best quality option is probably Chinese (in some form or another).

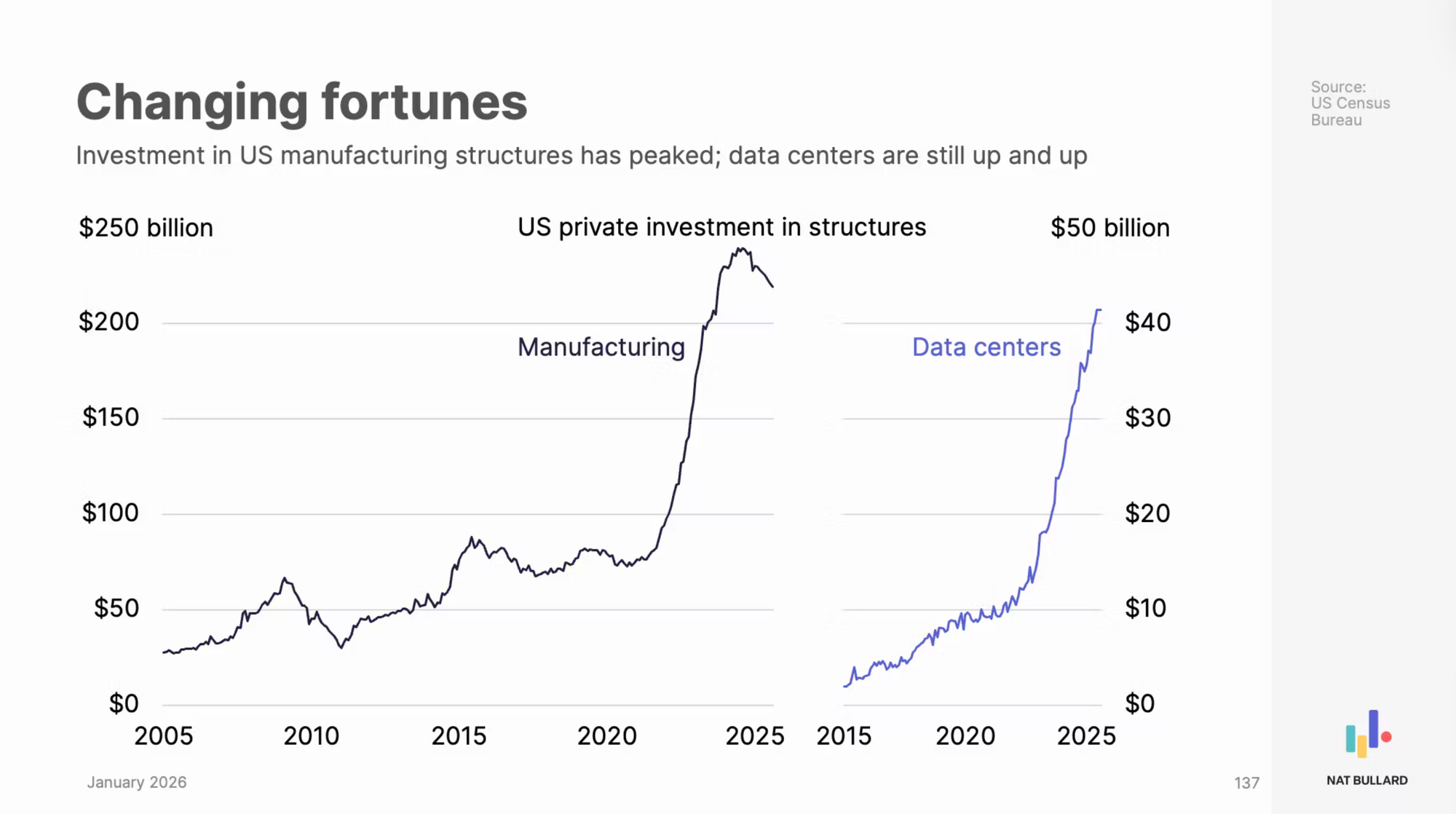

This one cool trick can starve manufacturers of capital.

Why is this interesting?

This slide really should blow your mind. It shows that, during most of the years of the Biden administration – both due to the Inflation Reduction Act and the supply chain reorganization prompted by Trump – the United States more than doubled its manufacturing investmenting.

Since Trump's election, two things have happened: the economy has slowed as a result of chaotic trade policy, and AI has sucked up most of the oxygen in the room. In both practical terms, and with many of the companies I speak with, a conversation with investors simply isn't interesting unless you can tell them what flavour of ChatGPT-like thing you're making.

What does it mean?

Data centres aren't entirely synonymous with AI, or even large language models (LLMs) like Claude, ChatGPT, or DeepSeek. But they're very, very related, and the companies making the biggest investments generally find their way back to this business model. The wealth creation prospects from AI are, at the level of the whole economy (i.e., GDP), immense. But these kinds of investments reflect an acceleration of the American business model of the past three decades: we'll design it, finance it, and maybe assemble some (physical) pieces of it, but we want others to make most of the rest of it.

If the United States is indeed hellbent on being the global AI superpower, one has to ask the question: is that all they will do? And, equally importantly, how many jobs are in that model?

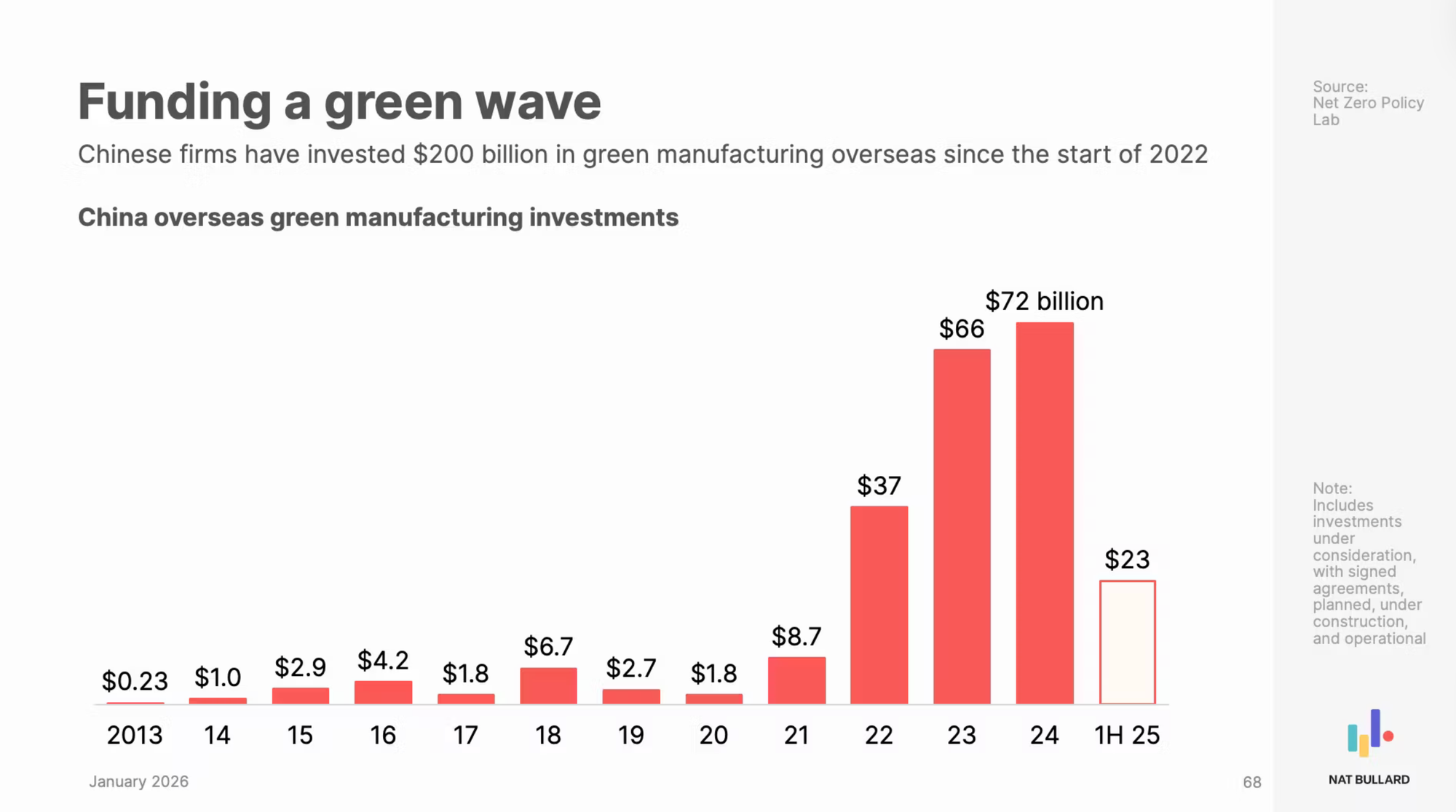

Red factories rising.

Why is this interesting?

This was actually probably one of my favourite slides in the whole deck. We're used to hearing about Chinese domestic investments in renewable energy manufacturing, but Bullard highlights this fascinating data showing that China is not only investing at home, but also abroad.

This mirrors research I highlighted earlier this year showing that China's investments through the Belt and Road Initiative are increasingly focusing on branch-plant manufacturing overseas.

What does it mean?

Chinese manufacturers face two significant challenges: domestic electricity regulations may soon eat into some of their margins, and many would-be Western buyers have been cautious about buying too much directly from China. However, third countries (e.g., Nigerian EV's) are one possible way to get around this, and some, like even Canada, may be more open to Chinese branch-plants if tensions with the United States continue, or deepen.

More renewable energy is, in fact, good.

Why is this interesting?

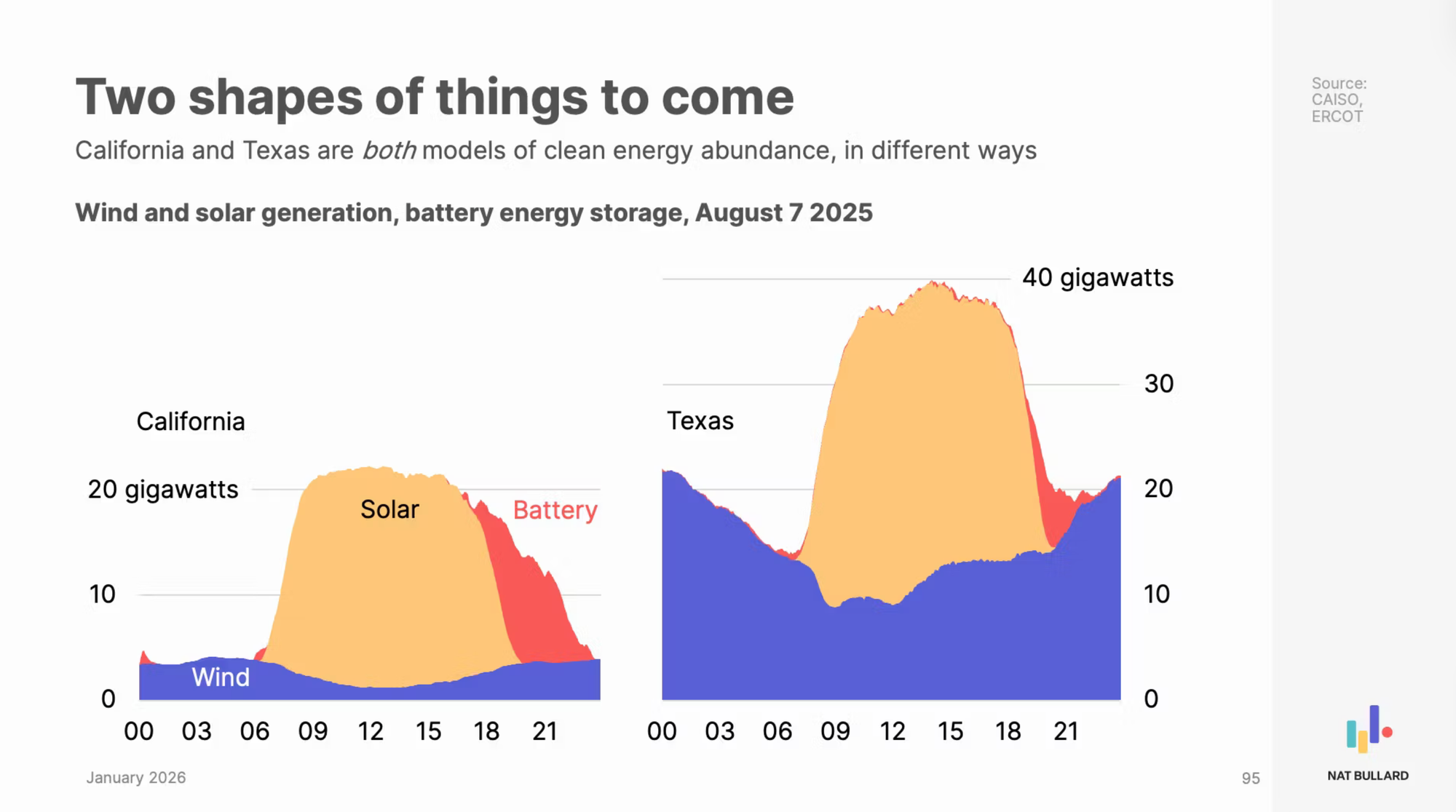

Even in global energy transition discourse, it's hard to think of two places that dominante the airwaves more than Texas and California (though, thankfully, Pakistan has now entered the chat). They're perfect foils for one another and they are the prism through which many American culture war issues are read. But as Bullard expertly pulls from the data from the arcane electricity systems operators (ERCOT and CAISO), these two states actually represent a convergence: building more renewable enegy is a winning economic proposition.

What does it mean?

Both states' power demands are growing in leaps and bounds. Texas reported 5% growth in the first three quarters of 2025, the fastest in the US. Texas' unprecedented investments in solar and wind are leading the nation and modulating prices while creating long-term energy resilience.

California is a unique creature in terms of solar. It hit 32% of all electricity generation in 2024, but its deployment of batteries is truly staggering. In April of 2024, batteries were the single largest source of energy on the state's grid. They keep getting cheaper, and California keeps deploying them.

As very, very wealthy economies with massive energy demands, these two states are showing how a generation-heavy (Texas) and/or storage heavy (California) approach can get you the energy you need at the cheapest price.

I'm with the kids, though:"¿Por qué no los dos?.

Transport fuels are cooked.

Why is this interesting?

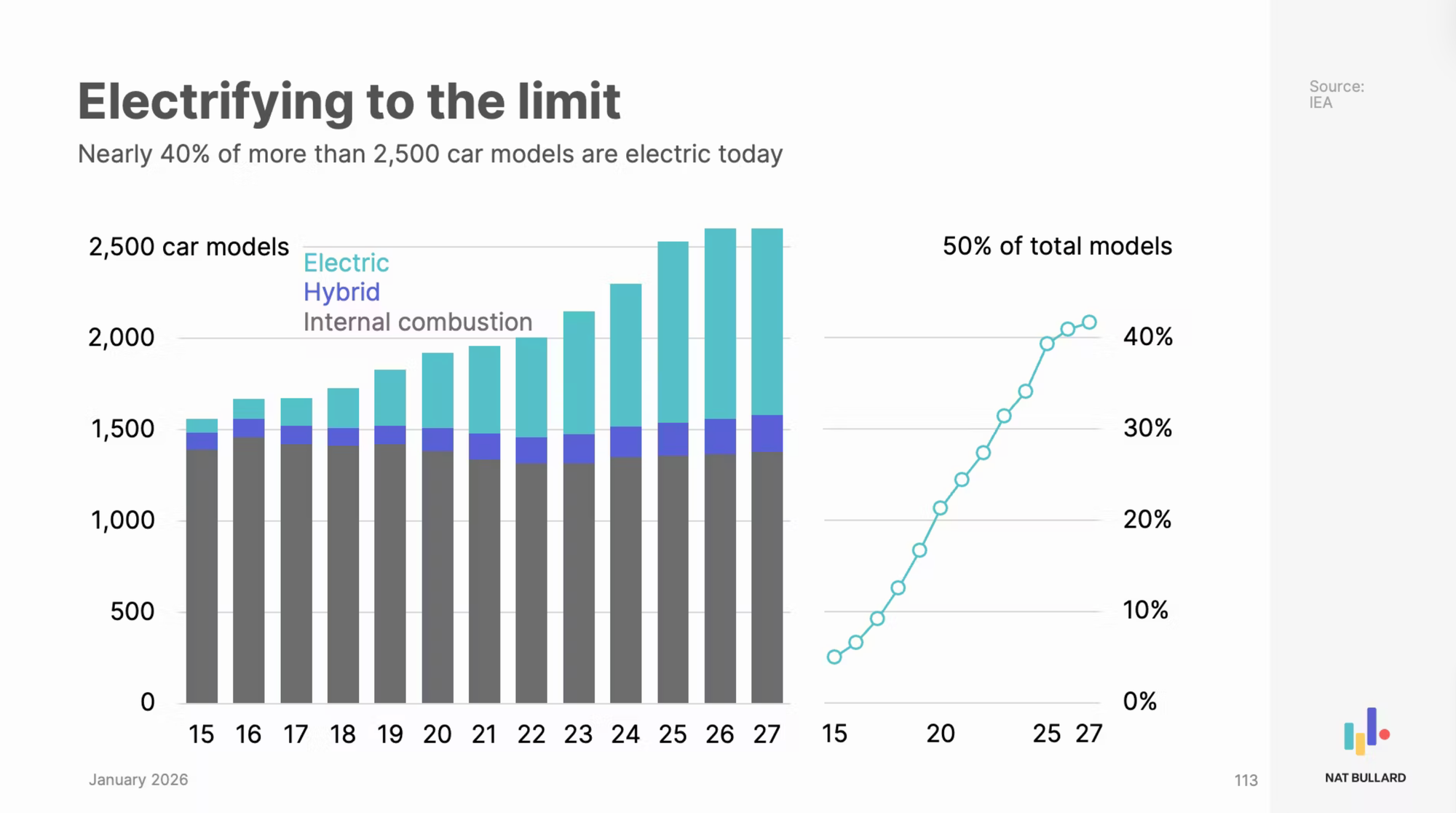

Transportation consumes about 30% of final comsumption of energy globally. In wealthy countries, passenger vehicles demand about 65% of all energy used. Every electric vehicle sold, therefore, is an attack on the foundations of fossil fuel production.

Instead of looking at the total production of vehicles, Bullard's slide here takes the somewhat more novel approach of looking at the share of EVs in terms of number of models rather than units. The story is clear: EV's have almost reached parity with combustion vehicles, meaning that in liberalized markets (i.e., not Canada or the US) you'll have a 40/60 split on the car lot of what kind of model you can take. The more proliferate these models become, this story implies, the more likely you are to buy an EV.

What does it mean?

There are two stories embedded in this, one about decarbonization and one about manufacutring.

The first is that transportation fuels are looking more and more cooked. The hippies at the Gas Exporting Countries Forum estimate that EVs will drive a "transformative eightfold increase in [electricity] demand by 2050." The IEA says that by 2030, EVs will displace 5 million barrels a day worth of oil consumption. Canada broke records at the end of 2024 by producing an average of 5.13 million barrels a day. Conclusions are left to the reader here.

The second is that Chinese vehicle manufacturers are winning, big time. By 2030, BloombergNEF predicts they'll make a third of all vehicles on the planet. Specifcally battery manufacturing is utterly and completely dominated by Chinese firms, both in conventional liquid electrolyte batteries (e.g., lithium ion) and in various forms of "solid state" batteries. Automotive innovation has long been a mainstay of Western economies; as they fall further and further behind on EVs, that mantle is now likely to shift.

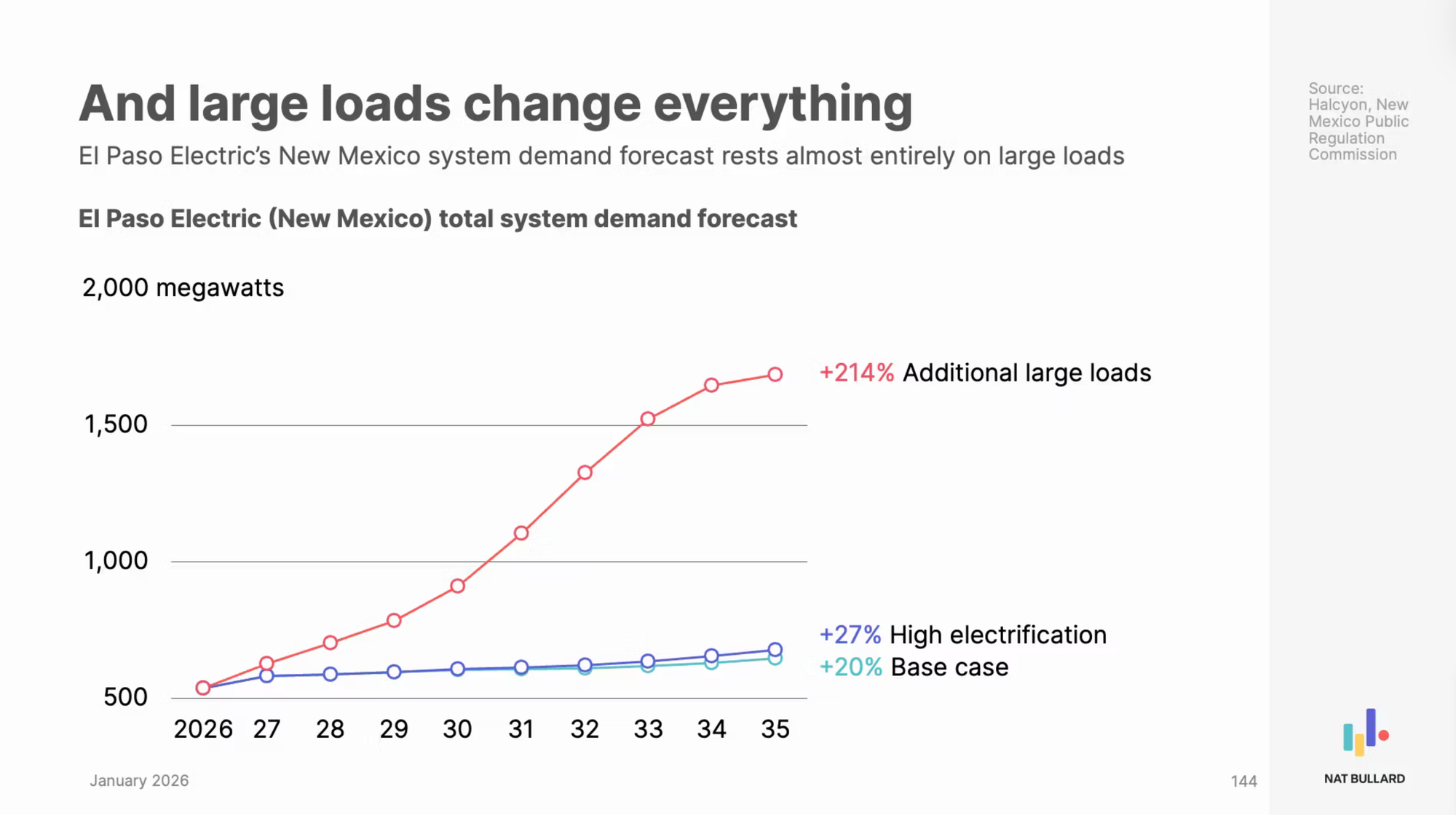

Why is this interesting?

Effectively every single forecast and scenario about energy in the world agrees on one single thing: we're going to need a lot more electricity. But the exact amount – and what its core driver wil be is utterly and completely bedevelling. I wrote thousands of words just trying to understand the answer to this one question in 2024.

Bullard references demand in New Mexico, but here in British Columbia, the story is even more extreme: 7,000 megawatts worth of industrial demand in the interconnection queue (about half our total consumption today).

The large load "question" is, importantly, somewhat unique to advanced economies. Most emerging economies are just generally hungry for more electricity, since their per capita consumption is so low and electrification is generally synonymous with increased prosperity. But for Western ones, the sudden (or not) addition of data centres and, in places like B.C., the potential for large hydrogen or LNG loads is what gives electricity forecasters heart palpitations (even if I think something I think unlikely).

What does it mean?

I see this as reflecting two key uncertainties: how AI-drivenbig data centre demand for energy will end up actually being, and how far economy-wide electrification goes in the next decade.

We also know, per slides 183 and 184, that we've both consistently over-estimated electricity demand, whilst also under-estimating the potential for electrification. And because the latter actually reduces the overall amount of energy and economy needs, this can create confounding outcomes, particularly if you're a Vaclav Smil-type who thinks every watt of energy from fossil fuels going into our systems needs to be replaced one-for-one with electricity.

This graph will therefore mean different things depending on who's looking at it: some see assured growth, some see over-estimation. I err slightly on the side of seeing this as an over-estimation, particularly in B.C. but the kicker is: having lots of (cheap, clean) electricity is never a bad thing.

The Art of Paying Attention

Part of what I love so much about Bullard's work is that he doesn't make predictions – indeed he ends the presentation with open questions. He clearly has a normative preference – a decarbonized, electrified world – but the stories he tells with the information he presents are not biased towards creating a sunny, "it's all working!" narrative. He's curious what the trends are, plain and simple, and putting them forward as an act of sensemaking.

In that respect, there's also meta-point he's making, which I think is worth dwelling on: the energy system is one of the most complex things have ever built. To "know" it is, in a sense, a fools errand. One can simply watch what one can concieve of, and then, with something perhaps resembling a "scout mindset" try to divide information into different categories of likelihood and usefulness.

Ultimately, the Bullard's whole project is one of paying attention in a very deep and reflective way. We could all learn a little from such a practice; I know I do.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.