In my last article on consumer protection and competition policy, I touched on the challenges around the fight over greenwashing. This is a topic I have had the privilege to learn a lot about over the years, including from some of Canada’s leading researchers and thinkers, such as Calvin Sandborn, Julien Olivier Beaulieu, Iris Fairly-Beam, and Grace Nosek.

In this post, I want to touch on a specific, and ongoing, legal fight right now over proposed consumer protection regulations that would, according to proponents, make greenwashing by companies harder. Detractors, including two BC and Alberta-based industry groups, say that these proposed regulations limit free speech. The stakes are simultaneously being cast as government overprotection and overreach (does it really matter if your container isn't actually compostable?), and as a direct threat to democracy.

To me, the stakes are indeed very much about democracy and freedom, but not for the reasons critics of these rules are portraying. But we'll come to that.

A Brief Genealogy Greenwashing

Greenwashing is an idea with a relatively recent history. What we mean by the concept today — that an organization, especially a private corporation, misleads the public about the relative environmental benefits of its actions or products — lines up more or less one-to-one with the history of advertising.

I think the simplest way to explain this is to work through the chain of causation in Western, industrialized societies from the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries:

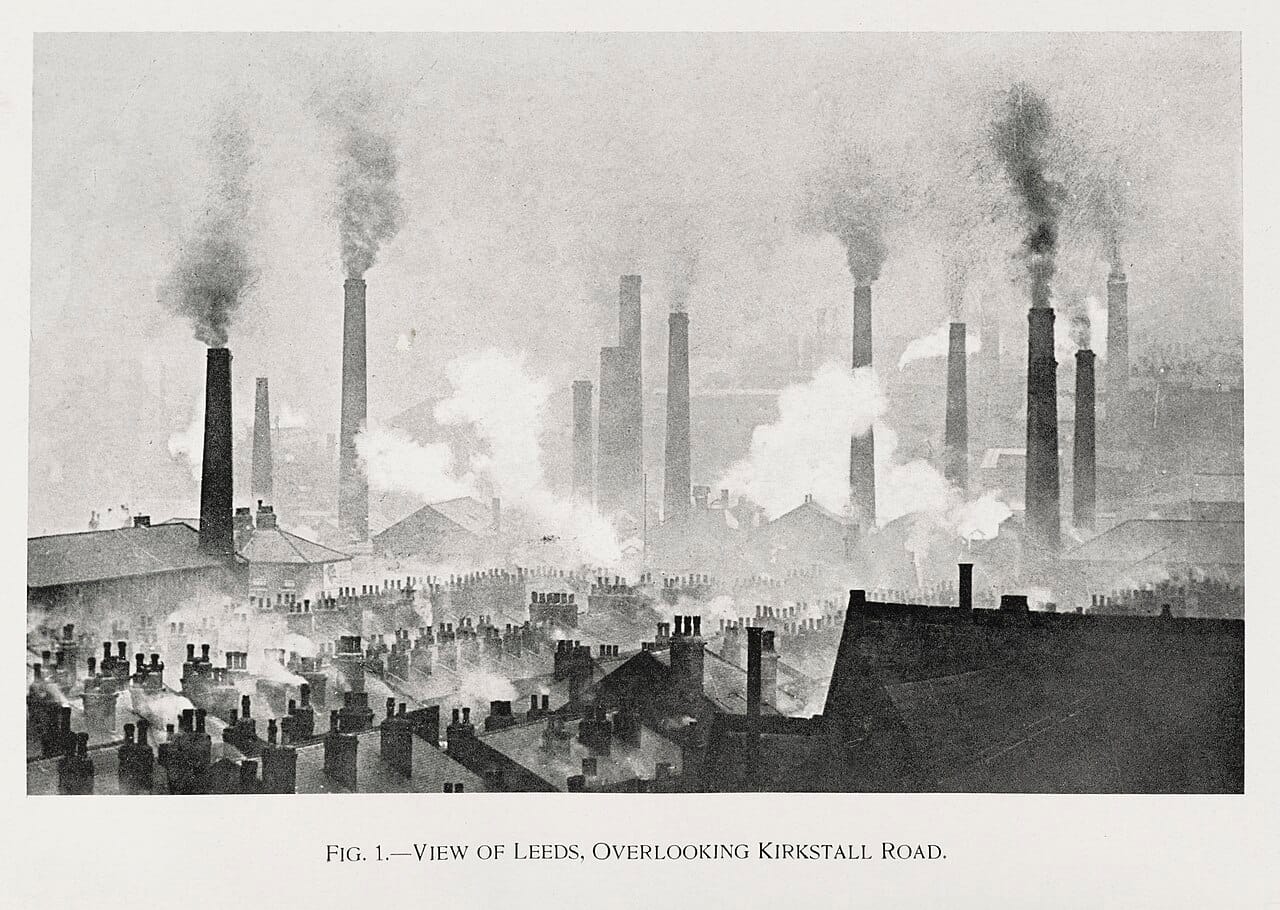

Industrialization created innumerable negative social and environmental impacts, even as it created immense (though unequal) wealth. As both individuals and societies became more wealthy, they had more free time with, education about, and access to natural spaces, the degradation of which became increasingly visually and later scientifically obvious.

Western environmentalism, in this very basic sense, is a response to the damage we caused in our own immediate, and later distant, natural spaces and systems.

Advertising is also tied up with this progression. As mass production of goods became possible, the geographies within which you could sell things increased, competition increased, and the desire to eke out ever more robust market advantages became self-reinforcing. Advertising became at first the art, and by the 1960s, the science, of tapping into the emotions and impulses of the public to sell whatever you could to whomever you could.

The basic principle that I think most people miss is that advertising is fundamentally amoral. It has no problems with using whatever messages, aesthetics, or tactics that it takes to sell something — if the client is paying enough, they can probably find a way to make it work. This is why the phenomenon of “woke” brands is so confusing to many: why would companies talk about something explicitly political, like gender justice, if they didn’t mean it?

The answer has two parts: firstly, a company isn’t a person, so it can’t “mean” anything (even if individual people in it do). And secondly, it doesn’t need to mean it, it just needs to sell.

But humans are finicky creatures. We don’t like too much of the same thing, we are profoundly creative, and, by another turn, suspicious. Western consumers, in particular, bombarded with advertisements for almost two hundred years have a profound scepticism and fairly high level of media literacy when it comes to the work of marketers. That’s why we’re in a perennial race to avoid getting “caught” by whatever the new flavour of the day is — despite the best efforts of ad-people.

Skepticism, however, only works insofar as you understand what it is you’re seeing. The more aggressively you can keep ahead of an audience’s media literacy, the more likely you are to sell them something, even in the face of profound mistrust. The momentum of this cat and mouse game can get so intense, as argued by French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, and practiced by BuzzFeed founder Jonah Peretti, that the very idea of personal identity can become a moving target, as people desperately seek to avoid some form of “capture.”

There’s one other important part, too, which I think many people also miss: the internal complexities of sincerity.

There’s the old quote from American consumer protection advocate and political radical Upton Sinclair that summarizes this nicely:

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

Having worked in climate change for fifteen years, I’ve had the opportunity — and often the privilege — to speak with people I disagree with on this issue constantly. It’s been my experience that most people I engage with on the issue are deeply sincere in the beliefs they bring to the conversation. Particularly where I live, in Canada, there are very few people who will tell you that nature is of no value, or that it doesn’t deserve to be protected, either for its inherent worth or the benefits it provides to us.

Rather, most people who could be said to be “anti-climate” are engaged in a complex series of psychological processes, relatively few of which are intentionally malicious. The social science literature on this is fascinating and diverse, with no definitive answer as to what exactly is going on, but a few elements are important to name.

Probably the most important of these processes is the idea of “motivated reasoning.” Druckman and McGrath discuss its application to climate change discourses in a brilliant paper, where they say:

Motivated responding can be thought of as answering a question different from the one that has been asked. For example, although a survey may ask a question along the lines of “Which of the following is true?” a respondent may consider it an opportunity to respond to the question “Which do you prefer?” or “What party/policy do you support?”

Importantly, however, they note that motivated responses (and the internal process that leads to them) motivated reasoning can overlap with other mental processes, some of which are biased to dismiss particular kinds of new information. For example, many people are directionally motivated by the fact that their livelihood or identity is related to political positions associated with not doing much about climate change. However, these same people (and in my experience this is very, very common) may also be seeking a particular type or aspect of accuracy in how they engage with relevant information that is both shaped by their cultural context and their material interests.

Druckman and McGrath explain:

Some studies find data consistent with accuracy-oriented updating. For example, Ripberger et al. explore how individuals perceive climate anomalies (departures from average precipitation and temperature) over 11 consecutive seasons. Here the experienced anomalies are the new information. The authors find a strong relationship between the objective measure of anomalies and respondents’ perceptions. Although they find some variations among extreme partisans, they note that these effects are small and do “not overwhelm the Bayesian process whereby both groups incorporate feedback… ” Individuals update in the direction of the information regardless of their prior beliefs about climate change.

Put another way: most people can take in basic factual information that doesn’t feel like it necessarily confronts their higher-order beliefs about politics or society.

But, as Druckman and McGrath later argue, being able to take in discrete pieces of information and accept them as factual does not then necessarily lead to a worldview shift in (1) what the problem is and (2) what solutions we ought to take about it. This is particularly true if that worldview shift would have negative implications for their material interests and cut against their social context. People don't tend to learn a few facts and decide that they want to radically shift the way they live, especially if that means swimming up stream of all of their immediate incentives and pressures.

It can be tempting to determine that these are just the natural human mental structures we work with and there is nothing to be done. While there is some truth to that, these mental structures are also always being shaped by societal forces. For example, American academics Jon Hanson and Douglas Kysar developed the idea of “market manipulation” to describe how advertisers can manipulate human perceptions in the service of selling their product. The easiest example of this is pricing something $9.99 instead of $10 to make consumers believe the cost of something is categorically lower than it really is.

There are, unfortunately, people and organizations who use these cognitive patterns to sow doubt and discord in the service of maintaining their own particular financial ends.

The Energy MixNicole Magas

The Energy MixNicole Magas

Unfortunately, this movement is well-resourced and motivated and sophisticated; as outright denial of climate change has proven less fruitful, their tactics have changed. The current wave of strategies are often called “discourses of delay,” based on the work of Lamb et al in 2020.

These scholars identify four overarching lines of argument, that then feed out into more specific instances, which define these delay orientations:

- Someone else should take action first: redirect responsibility.

- It’s not possible to mitigate climate change: surrender.

- Disruptive change is not necessary: push non-transformative solutions.

- Change will be disruptive: emphasize the downsides.

These represent lines of argument that can fit into an individual’s mental models of the world, where they do in fact want things to get better, while still supporting a structural status quo (that may even hurt them).

I distill all of this context into a need to hold three truths simultaneously:

- Most people are trying their best to interpret information they receive — and respond to it — in good-faith ways, but do so through the lenses of identity and personal interest.

- People's view of what is good for society as a whole is shaped by their social context and personal interests, for good and for ill. No one is immune to equating at least some of their personal interest with that of society's.

- A select group of people are looking to manipulate the public at large by preying on how we know humans intake information and make decisions; they are very well-resourced and very sophisticated.

A "Chilling Effect"? The Current Canadian Debate Over Greenwashing

In December of 2024, the Independent Contractors Association of BC (ICABC) and the Alberta Enterprise Group (AEG), two large and very political industry associations, came out swinging against Bill C-59, an act implementing parts of the 2024 Fall Economic Statement.

Specifically, they took issue with and later sued the Government of Canada for changes to the Competition Act that, as laid out in the bill:

- Would “modernize” the merger review regime, meaning that the Government would take a closer view at the merging of companies and pause particular ongoing mergers if it felt approval might be needed.

- Allow the Commissioner of Competition to review past agreements between companies, and other aspects of their activities, to ensure that businesses making claims about environmental benefits “must be supported by adequate and proper substantiation.”

- Create new administrative procedures to ensure that these activities were implemented by regulated parties.

The ICABC and AEG lawsuit opens up with 46 interlocking statements about the purported illegality of the Government’s actions with these changes. There was much ink spilt over how fair or unfair the proposed changes were, with particularly loud and fearful claims from industry groups, like the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), saying that:

“The effect of this legislation is to silence the energy industry and those that support it in an effort to clear the field of debate and to promote the voices of those most opposed to Canada’s energy industry.”

Silence is a particularly interesting word to use, and one that was repeated often.

While it is undeniably true that this legislation would, and has, quieted oil and gas lobbyists’ written communications regarding the environmentally friendly future of oil and gas and the glossy websites, like the Pathways Alliance, that came with it.

It is also true that in 2024 alone, the Federal Minister of Natural Resources, as just one official, met with different oil and gas representatives at least 1,135 times, effectively three times a day. If we take the comment about quiet to mean that the oil and gas industry is, or would be, denied the opportunity to argue for itself, both to the public and government, this statistic alone (let alone marketing budgets, and other forms of lobbying, sponsorships, etc.) strains the credulity of that claim.

One of the things I found most fascinating in their argument was their claim that these changes would deny companies’ Charter right to Freedom of Speech.

Corporations, as proven in litigation since 1982, do have access to this right under the Constitution. However, this and every other right is also subject to reasonable limits. The tradition has been established, however, per the 1987 Institute of Edible Oil Foods et al v. Ontario, that governments are indeed allowed to regulate the activities of companies, including their speech, if it is deemed in the public interest.

As the judge says in the Institute decision, the Ontario regulation that stipulated that margarine could not be coloured the same as actual dairy did infringe on the company’s right to freedom of expression. However, was that infringement part of a “reasonable limit” of that right? Justice McKinley felt it was:

I am satisfied from the evidence presented by the respondent that protection of the dairy industry in Ontario is of substantial economic and social importance. In furthering that objective, the colouring of margarine as required by [the Ontario legislation] clearly has a detrimental effect on both the required methods of production of margarine and on the portion of the edible oils market likely to be available to margarine producers. However, such results do not unusually follow the regulation by government of commercial activities. I do not consider that the restriction on the applicants' freedom of expression is disproportionate to the very important legislative objectives involved in this case. [emphasis added]

And so, in the 1980s, the Ontario Supreme Court ruled that protecting dairy industry profits and jobs was important enough to limit other companies’ “free speech.”

Does it seem reasonable or likely that the Government of Canada would be within its rights to limit certain types of claims by companies or associations to protect the public discourse regarding what are real solutions to an existential problem like climate change?

Take it from An Actual Lawyer

Iris Fairley-Beam is someone I’ve had the pleasure to know for several years now. She’s done amazing work to advance a number of powerful environmental law ideas and causes, in particular, working with the University of Victoria and Quebec Environmental Law Centres around consumer protection and greenwashing.

She was the one who alerted me to the specific case of the ICABC and AGE case against Bill C-59 and was kind enough to both summarize and add commentary for each. I adapted what she wrote and added a little of my own colour, but you can read her whole summary below.

Iris lays out what she feels are the seven major arguments about the proposed regulations and I quote from her directly below to summarize them:

- The rules are unnecessary since we already have policies against misleading or false claims by companies.

- The rules will have a “chilling effect” on companies because they’ll be uncertain about what they are allowed to say (and what they may get sued for).

- The rules will prevent businesses from meaningfully contributing to Canada’s political dialogue about the future of natural resources.

- The rules would prohibit or limit actual truthful and accurate information from being used, just because the company doesn’t have a readily available source of proof for it.

- The rules would demand definitive proof about solutions for which no such proof is possible.

- The rules only apply to businesses and not nonprofits, which is unfair.

- The rules would create the risk of politically frivolous lawsuits.

Line by Line

The most nuanced aspect of Iris’s rebuttal is with regard to the claim that the rules are unnecessary. On the surface, this claim makes all the sense in the world: we already have consumer protection, so why do we need new rules?

I took away two big things from Iris’ arguments on the question of necessity:

Firstly, in most cases, a claimant in a consumer protection case is responsible for proving that a company broke the law or misled the consumer. Because of the vast complexity of the claims being made by some companies — “we will reach net zero by 2050” — it’s impossible for a single consumer, or even sophisticated groups of consumers, to prove the falsity of a company’s claim without information only the company would have. Furthermore, the Competition Commission doesn’t have limitless resources, either, so investigating big claims can take a long time.

So these new rules create a “reverse onus” on the company to show, in advance, that when they make a claim, they can back it up. And the flip side is simple: if you can’t (reasonably) back it up, don’t say it.

Secondly, she deftly argues that existing consumer protection law is focused on particular products. What’s the product in a net-zero future that’s being sold? And who are the beneficiaries?

As Iris writes, it was “unclear” whether the previous requirement to substantiate a claim extended to all of the claimed environmental benefits of a product. As I read what she’s saying, people were probably quite good at making specific claims (“this dish soap does not contain benzene”), but the bigger they get (“Canada’s oil will be zero carbon by 2050”) the less clear it was how high the burden of proof is. We needed to fix that, this legislation argued, and as Iris says:

[the] new rule says if you make a statement that a business or business activity protects or restores the environment or mitigates the causes or effects of climate change, you must base this on substantiation “in accordance with internationally recognized methodology.”

As an aside: this reminded me somewhat of the criticisms of Lina Khan about the fixation of much of competition policy on costs of particular goods, and not on broader market effects. (I wrote about that in my last article on consumer protection).

The question of what an "internationally recognized methodology" is is a significant thrust of the case against the legislation, but its presence is more or less a placeholder for installing a credible, recognizable standard that will come out of consultations on the actual rules, not in the legislation itself.

The chilling effect argument, as Iris summarizes, is that “the uncertainty in the new rules will cause companies who are not 100% certain whether their statements violate the law to self-censor and not talk about their environmental impacts even though they are accurate. “

She argues convincingly that the ICABC and AEG proponents are, first of all, holding legislation to an impossible standard: it will never be 100% clear the first time it’s written, particularly when it’s about such a massively contentious issue.

More importantly, I think, she argues that the current “scaremongering” about the rules’ potential impact is having a far greater impact than they would have in practice, because of the various administrative processes in place to limit abuses — and punishments for mistakes — under the Competition Act.

Lastly, I will quote her in full on her final point on the question of whether or not the legislation would have a “chilling effect,”

The Statement of Claim argues that the fact that some businesses have taken statements off their websites is evidence of the chilling effect. This is a problematic logical leap: the rules may in fact be having the intended effect. One would need to know more about the nature of the statements, the evidence backing them, and indeed their misleading or potentially deceptive nature, before you can draw the conclusion that taking down the statements was due to a chilling effect. [emphasis added]

Mike de Souza wrote about this in the specific case of the major oil and gas group, the Pathways Alliance, when they took down content on their website when the new rules came out. Were they “telling on themselves,” as some seem to think?

The NarwhalMike De Souza

The NarwhalMike De Souza

The other claims Iris identifies get steadily weaker and easier to rebut as they go along, from the claim that the rules prevent businesses from participating in politics (no, it constraints the commercial statements they can make); to whether or not they need 100% accurate information (no, just something reasonably defensible); and that the rules will lead to frivolous lawsuits (no, the Bureau can stop that, and lawsuits are too expensive).

Some People are More Equal than Others

With the horrors underway in the United States right now and elsewhere in the world, the concerns of greenwashing might seem quaint. Indeed, how is democracy hurt when a company says their dish soap is “non-toxic” (whatever that means), or an oil company says that they’re “working towards net zero”?

But particularly with an eye towards what is happening in the United States, it’s important to consider what it means for a company to say something at all:

In 2010, the Citizens United case changed American politics forever. The US Supreme Court agreed with a corporate-funded campaign to classify all spending by large companies, including partisan political advertisements, as a form of free speech. To try to limit this spending — sorry, I mean speech — was, in the majority of the court’s view, to violate the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

The decision hinged, in part, that the First Amendment considers not only individuals, but associations of individuals as part of its protections – even though the inclusion of associations as part of free speech was initially thought of as part of protecting freedom of the press. But because corporate political action committees (PACs) are “associations” of people (read: companies), the court decided that the US Government had to uphold a virtually limitless interpretation of the First Amendment.

The results of this decision have been, to say the very least, transformational.

Brennan Center for Justice10015

Brennan Center for Justice10015

The most important criticism of Citizens United to me is that if we assume (1) that companies are indeed people and (2) that spending is the same as speaking, then certain types of people have a vastly different ability to speak than others.

The problem with the First Amendment is that it was designed when someone could get up on a literal soapbox in a town square and start to talk politics. That's a freedom we should not only obviously protect, but one that seems more and more under threat, in the US in particular. What it didn’t imagine is that an association of "people" would have an appreciable portion of the total national wealth that they could spend to design campaigns that would draw on human’s most base psychological structures, and be able to spread those campaigns to every possible corner of the land, even in people’s most intimate, seemingly "apolitical," spaces.

Mother JonesRebecca Leber

Mother JonesRebecca Leber

This is, in my view, a far more worrying “chilling effect.”

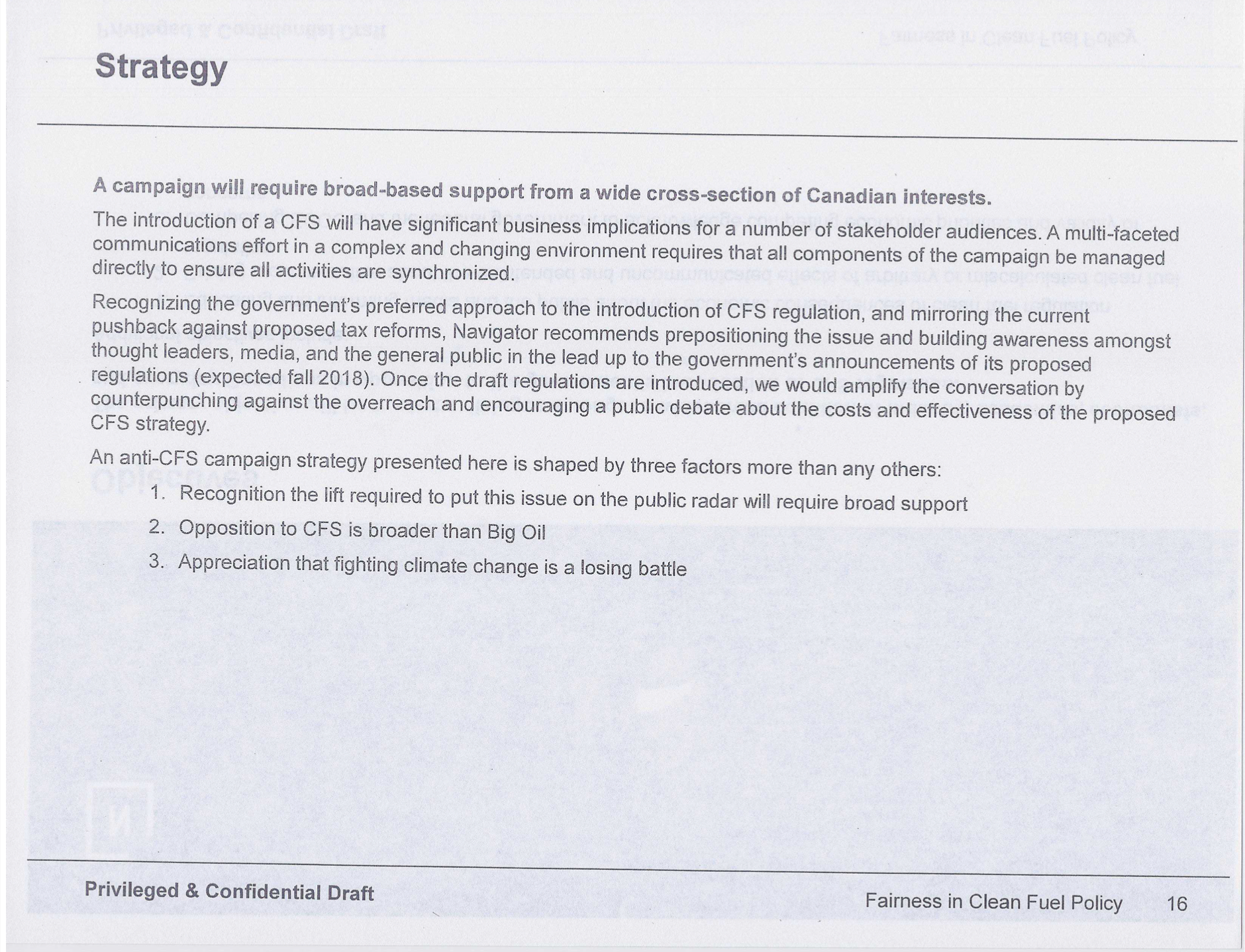

A case study of how far-reaching the power to speak can be taken is the oil and gas-funded campaign called Canadians for Fairness in Clean Fuel Policy.

When my friend Grace Nosek, an award-winning misinformation and corporate speech researcher and lawyer, first explained this campaign to me, I was shocked. The bald-faced nature of this campaign, developed by a slick public affairs and government relations firm, Navigator, is pretty astounding.

Navigator did some very impressive research to develop a series of messages and strategies against the national government's then-proposed Clean Fuel Policy. Their strategies draw on decades of campaign experience in how to shape broad social perceptions of an issue in a way that benefits a particular group As they detail in the deck, the central thrust of the work is to make it clear that the argument about the policy is not about climate change, and that it is not industry who will be the primary beneficiary if it is softened or repealed.

Now here's where it gets sticky for a lot of people: it's perfectly rational for an industry to argue for something that would benefit them. In a free and democratic society, it's perfectly fine for people to explicitly argue how they think society ought to be.

But the Clean Fuel Standards campaign shows that the companies involved knew that the public wouldn't be very sympathetic to "we don't want to do this because it will hurt our bottom line," and so they developed a secretive campaign to twist the story away from that, and make it seem like it was purely the impacts on the public that were the top concern. That's when we start to get into worrying territory.

I think the most stomach-wrenching aspect of the whole document is where Navigator identifies one of its critical factors shaping the campaign is "that fighting climate change is a losing battle."

What's written in that one line is a nation-defining decision with unimaginably vast consequences, involving our laws, our economy, our landscapes, and, most importantly, our people.

Is, for example, protecting farmers in the Prairies a losing battle? People whose livelihoods are already threatened by increased drought.

What about the people of Delta, where their lands face ever-more inundation by rising sea levels?

How about the Arctic Caribou, their magnificently long migration patterns are threatened by the loss of sea ice?

The list goes on, and on, and on.

Fundamentally, this example is why greenwashing is truly a test of democracy. Because, to the point of the court case, it isn't that we need stronger regulations to hold someone to account if they lie about what's in the dish soap they sell. What we need are rules to ensure transparency and fairness about who gets to tell stories about what our future can – and should – be. It's about policy, not products.

While the details of the changes to Canada's Competition Act will and must be worked out, its fundamental challenge to everyone is simple: prove it. If you're confident that you have a solution that works, or that your product has genuine benefits to offer people, then show your work. And if you don't feel you have a reasonable amount of proof – enough proof to, say, keep up a website with your research on it – then don't make the claim.

What's not lost on me is that these proposed rules (and perhaps those who still seek to shape Canadians' mindsets can take comfort in this) do not seem to prevent another Clean Fuels Policy-style campaign from being run again. The new rules would just limit some of what the companies and their associations can say if they do not have clear evidence. In light of what that campaign, and others like it, represent, that seems like a bargain.

Greenwashing may seem like a niche case in a fight for democracy. It's no surprise to hear from me that I believe climate change itself represents a fundamental threat (and more and more every day) to our democracy, but I see this fight as only one of many instances of a broader battle over our democracy.

The United States is the cautionary tale here. Citizens United gave those with the most money virtually unlimited abilities to spend and shape elections, which enabled the melding of private interest and governmental power to reach its zenith in the form of Donald Trump. Worryingly, that melding is now deeply reciprocal: Trump fights to reshape American taxes and policy to benefit his elite supporters, and entities like Fox News actively avoid any mention of tariffs in their broadcasting to preserve support for Donald Trump. They are not the first, and they will certainly not be the last company that will get in line with that regime to stay profitable – and powerful.

The Competition Act changes, if they survive the current election, will not "save" Canadian democracy; indeed, they are not intended to. They merely rebalance the playing field of who gets to tell particular kinds of stories, and what their responsibilities are when they do so. That has benefits in terms of fairness and representation, but reversing the frightening decline of our battered and creaking democracy will take much more than that, and go far beyond what government alone can deliver. Democratic and social vibrancy will take a reinvestment – and I believe re-imagination – of our basic social compact, something we all need to spend much more time considering and acting on.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.