I read a fairly diverse amount of media, so, I've seen the score of articles bemoaning how poorly Canada's economy is doing, and an equal number raising trumpets to broadcast our unstoppable successes. The truth is somewhere in the middle. The main points I keep hearing about that speak to the strength of Canada's economy are related to GDP and population growth, specific sectoral growth metrics (especially the tech sector), and the stock market. In my mind, those numbers really miss the reality on the ground.

The biggest one that continues to worry me the most is inequality.

Canadian HR ReporterJim Wilson

Canadian HR ReporterJim Wilson

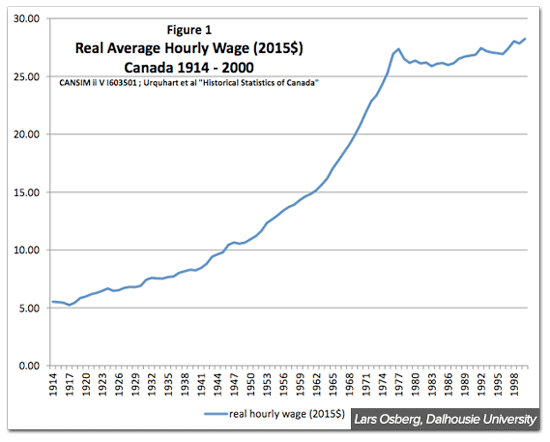

The Centre for Future Work is highlighting that wages are growing at a faster rate than prices for the first time in years. While this is good, it hides the structural challenges that Canada's economy has faced over the years, especially since the boom of inflation in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and supply chain disruptions of COVID-19. As has been shown in many different studies over the years (e.g., 2011, 2016, 2017), many of Canada's lowest-income people have fallen behind the growth of wages for wealthier people, and indeed the gains within different economic deciles are quite uneven.

The crux of all of this is that lower-income, and now middle-income people continue to fall behind. While some of this lost income has been offset by cheaper consumer goods, as we know today, the rise in the price of food and housing is hitting all Canadians where it hurts.

I worry about this for many reasons, fairness and equality chief among them, but even in more straightforwardly "economic" terms (i.e., GDP), this is bad for us. Inequitable distributions of wealth wreak havoc on an economy's ability to thrive over time: it depresses consumer demand; lowers people's ability to be entrepreneurial; increases social distrust and animosity; and limits the productive capacity of people to push forward new ideas.

How many brilliant inventors, entrepreneurs, artists, and scientists are not advancing our society because they're living hand to mouth? In my mind, the answer is too many.

The story of inequality in Canada is not a straightforward, linear one. First and foremost, when we're talking about inequality, we're often talking about economic inequality between non-Indigenous populations. The dispossession of Indigenous peoples is the original sin, if you will, of economic inequality in what we now call Canada. Addressing this via landback and cashback, as the Yellowhead Institute has written about extensively, will be part of addressing these old wrongs. In addition to that, however, this is still more to that story.

How did this start?

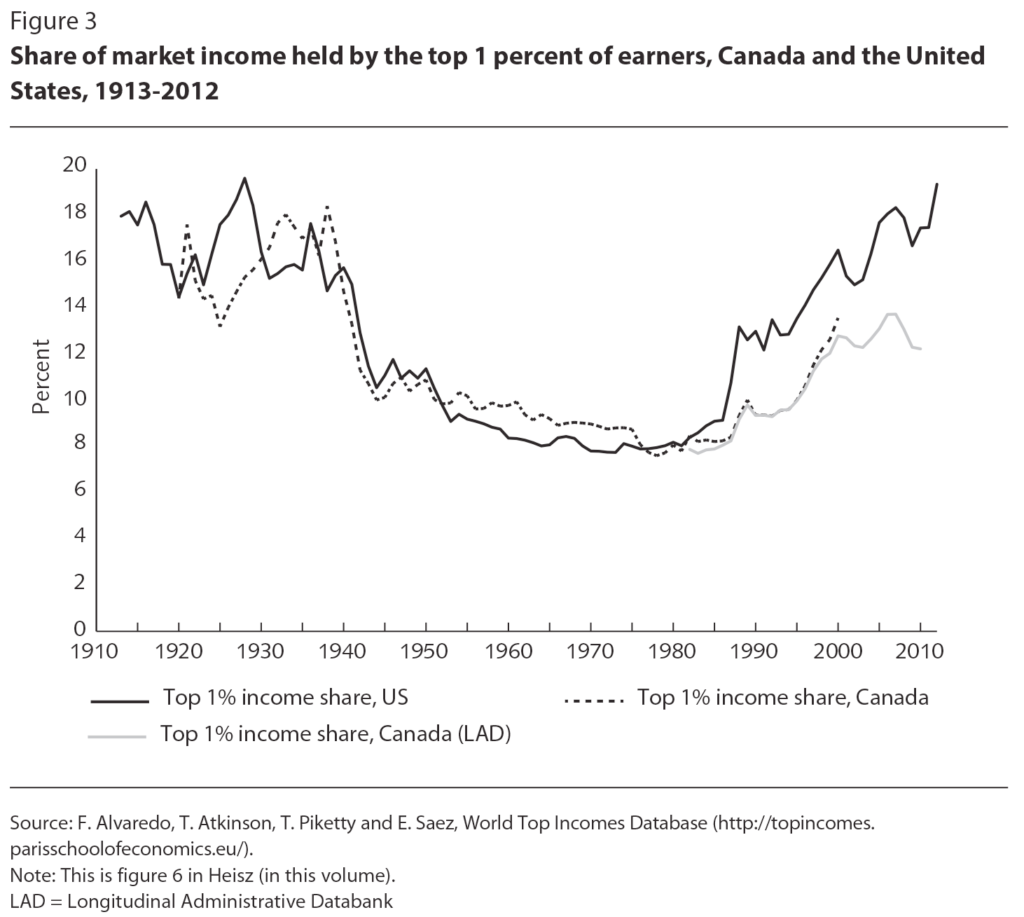

When we're talking about contemporary economic inequality, which is a story that now includes everyone in Canada, that story seems to always find its way back to the 1980s. The story goes something like this:

After a burst of investment in post-war social democracy in Canada, there was a material growth in the wealth of all Canadians (though, white men were the principal beneficiaries). After inflation hit in the 1970s and 1980s, however, the Federal Government found itself in a greater and greater deficit (especially with health transfers and high-interest rates on existing debt), and this culminated in repeated budget cuts and eventually the "Hell or High Water Budget" by then-Finance Minister Paul Martin. Factually speaking, the budget involved massive cuts - including an 18.9% reduction in total spending for the Government of Canada, massive cuts to business subsidies (+60%), and the folding of most transfers to the provinces into the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST). This was on top of existing cuts as Naylor, Boozary, and Adams note:

Six federal budgets between 1985 and 1995 variously scaled back the [gross national product automatic "escalator" funding increases] on combined health and social cash transfers or completely froze payments. In a 1991 background paper, Alistair Thomson calculated that health transfers cumulatively reduced by $30 billion from 1986/87 to 1995/96. Further reductions through to 1998/99 trimmed another $11.2 billion relative to the 1977 agreed terms.

In short, we cut the Canadian social safety net dramatically at the same time as economic conditions were uncertain and we've never quite recovered to prior levels, despite increases since then under successive governments.

Where are we now?

When we talk about inequality, we're at the confluence of a number of related, overlapping concepts. I was inspired by how the BC Expert Panel on Basic Income talked about this when they discussed poverty. As they say:

Some poverty scholars focus on (the lack of) economic well-being - that is, they measure deficiencies in quantifiable factors such as income, wealth, or consumption. Other scholars focus on capability poverty, as advocated by Nobel Prize Laureate Amartya Sen, defined as the actual opportunities a person has and their capability to achieve the various things a person has reason to value, such as good health and participation in society. A Sen's definition, poverty is complex and multi-faceted and moves beyond a simple lack of income, with elements that resonate with [the Panel's] goal of moving towards a more just society.

What I like so much about this definition is that it grapples with the complex nature of not only what poverty is - generally a lack of material wealth - and what it does - limits human flourishing. Understanding the lack of human flourishing is a complex task and beyond what I have capacity to fully engage with her, so, let's break down inequality into a few specific metrics.

Poverty

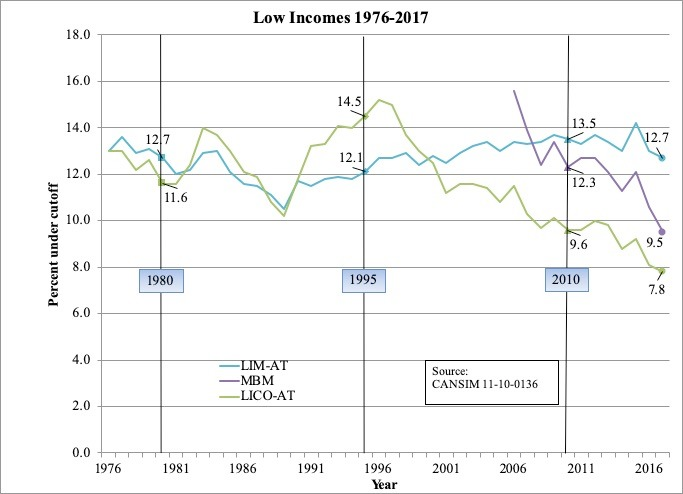

Again, the Expert Panel has some good summaries here. They note that Statistics Canada has three measures for low income: the low-income measure (LIM), the low-income cut-off (LICO), and the Market Basket Measure (MBM).

Both the LIM and LICO compare and family's income with a predefined income threshold. The LIM threshold is one-half of the median income in a year, while the LICO threshold identifies families who spend more than 20% more of their income on basic household goods (i.e., food, shelter, and clothing) than the average family.

As inequality increased, the LIM and LICO measures diverged and became unhelpful in baselining actual poverty levels. The MBM was developed to address that, where they defined a modest 'basket' of basic expenses and then compares that against average family disposable income (after taxes and non-discretionary spending). It is important to note that it has many, many criticisms, including and especially that it does not sufficiently price the cost of housing and that, as an absolute measure of poverty, it doesn't include a sense of how the lowest income people in society are or are not being included the outputs of new economic growth.

Interestingly, as the Panel noted, the poverty rate (as defined by the MBM but also when compared against LIM and LICO) has been declining across the country since 2006.

As Nick Falvo put in a fabulous blog post, the different data sets here show us different things:

"Use of the Low-Income Cut-Off (LICO) would suggest that poverty in Canada has decreased dramatically since the mid-1990s.

Use of the Low Income Measure (LIM) would suggest that poverty in Canada has seen mild fluctuations since the mid-1990s.

Use of the Market Basket Measure (MBM) suggests that Canada has seen a major decrease in poverty over the past decade."

As I parse this particular story, my conclusion is something along the lines of: the number of Canadians living in raw, material deprivation appears to be decreasing as compared to spikes in the 1990s, but the ability of low-income Canadians to participate in the benefits of increased economic outputs in relative terms appears fairly flat. Less starvation, but little change in human flourishing.

Income Inequality

As a relative marker of our economic success, income inequality is a different story. Income inequality has continued to rise since the late 1980s, with meteoric jumps at various points, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic (despite there also being some material gains in wages and wealth for lower-income people).

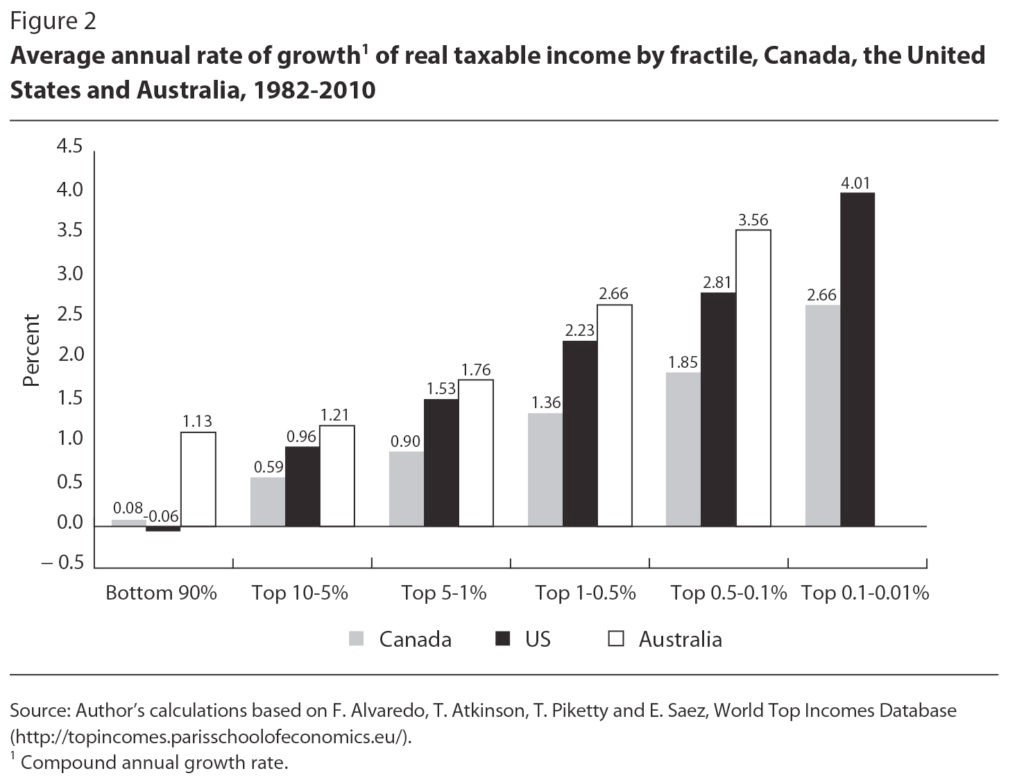

And when you compare those income growth rates, the number is starker. Keep an eye on the numbers at the bottom of this graph, these are not equal quintiles across the economy.

90% of Canadians saw their income grow by 0.08% from 1982 to 2010, while the top 0.1 to 0.01% saw their incomes grow by 2.66%.

As you look at other proxies for economic inequality, a favourite of some is the pay disparity ratio between CEOs and average employees. As the CCPA covered in 2021, those numbers are stark. As of 2019 data (and these numbers have not gotten better since then):

- The average CEO of a top-100 company made two-hundred and one (201) times as much as their average worker.

- The average CEO of a top-100 company made $10.8 million (CAD) a year in 2019, compared to the average individual income in Canada of $52,061 (in 2018); the 100th best-paid CEO in Canada made $6.3 million in 2019.

- There were four men named Paul and four women in the top 100 CEOs in Canada in 2021.

It's important to caveat that the 100 top CEOs are not representative of all CEOs in the country. We are, after all, a country mostly made up of small businesses (In 2022, businesses with 1 to 99 employees comprised 98.0% of all employer businesses in Canada), but it speaks to the disparities that exist between the highest echelons of Canada's elites and, well, the rest of us.

Wealth and Debt

Canadians are very wealthy, in global terms, and yet it is often noted that Canada has a debt problem. We have the dubious distinction of having the highest household debt in the G7 and one of the highest in the OECD.

Unfortunately, this is a story that is not getting better over time.

Canadian wealth also continues to rise, however. Maria Solovieva at TD Economics shared data on Canadian household Balance Sheets at the start of 2023 showing that:

Canadian household wealth climbed higher for the second quarter in a row, rising by close to $520 billion (+3.4% quarter-on-quarter) in the first quarter of 2023 – building on a 0.9% to close out 2022.

And that,

Again in net worth was due to both higher valuations of financial assets (+3.0%), advancing for the third consecutive month, and rising real estate prices (+2.7%). The recovery in real estate valuations came after three consecutive quarters of decline, and was supported by low home inventory levels.

Less recently, but more starkly, Statistics Canada said in 2020 that

"Household wealth reached $12.9 trillion in the fourth quarter of 2020, up $1.2 trillion (+10.5%) from the end of 2019. While the wealthiest households (top 20%) held more than two-thirds (67.5%) of all net worth in Canada, those in the lowest two wealth quintiles—who accounted for 40% of all households—held 2.5% in the fourth quarter of 2020." [emphasis added]

This is a purely financial view of what wealth means, however (and most of these analyses do not adequately recognize the massive role of inflated real estate in "wealth creation). The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) did a great piece on "comprehensive wealth" as a measurement methodology in 2018.

They found that Canada performed the worst of all G7 in growing its comprehensive wealth and that we relied largely on our vast amounts of natural capital (which we continue to reduce and destroy) to bump our numbers up.

What do we do now?

I'm not going to sit here and spin a yarn about how there's "one easy thing" we could do to address inequality in this country. Taxes are a part of the story, but so are housing reform, changes to the immigration system, significant changes to the social assistance system, and how people like me, economic developers, think about and do our work. The reading I have done suggests to me that while we have made some progress on removing material deprivation for everyday Canadians, our current economic system is phenomenally precarious - not just for low-income workers struggle to get by, but for governments and businesses, too, always trying to stay one step ahead of the next crisis.

Government of B.C.

Government of B.C.

The BC Expert Panel on Basic Income is one of the most interesting and comprehensive efforts in recent history to think about what a better economy would look like, making a total of 65 recommendations. Broadly speaking, they said BC (and arguably most of Canada) should:

- Target programmatic reforms to Disability Assistance to turn it into a basic income for people with disabilities.

- Reform Temporary Assistance to streamline access and reduce the likelihood of people becoming caught in a cycle of poverty.

- Provide far greater health care benefits to all low-income individuals

- Provide housing support to all low-income individuals (e.g., by combining support and shelter allowances into a single fund).

- Provide intensive work supports to targeted groups that have faced systemic exclusion.

- Enhance support for low-income families, young adults, and those fleeing violence, such as training, cash transfers, new types of funds (e.g., a BC Educational Bond), and new tax programs.

- Improving precarious employment through things like gig work employment standards, developing new Industrial Councils, and rationalizing definitions in law and programs.

- Radically shift how benefits are delivered to make them more generous, easier to access, and dynamic in the face of changing economic conditions.

The list gives me hope since it's a series of tangible things that a government could do to address economic inequality and improve the social conditions in our society relatively quickly. By its construction, it focuses mostly on those facing historical and ongoing marginalization in our society, but it's helpful to think of it as a foundation. An economy, to use a metaphor from Chris Anderson and David Sally aptly retold by Malcolm Gladwell, is a "weak link game," like soccer, where it doesn't matter how good your strongest player is, what matters is the difference in skill between the "best" and "worst" player. Play ball!

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.