After decades of invisibility, Canadians and Americans have become increasingly aware of how important it is to have laws that protect consumers from getting taken advantage of on an individual basis and those which ensure companies cannot stamp out their competition. We call this work, respectively, consumer protection and competition policy.

For the children of the 1990s, many of us vaguely remember now-sainted billionaire Bill Gates getting his knuckles wrapped by the US Government and European Union for the anti-competitive practices of Microsoft. Lovable, sweater-wearing nice-guy vibes aside, Bill Gates, rather than programming talent, is most accurately remembered as being a ruthless businessman who crushed, bought, or otherwise beat out competition to make Microsoft one of the most dominant and powerful companies in the world.

Linking to a YouTube essay that includes history on Microsoft and Gates' role in the creation. of the PC, but consider a $5/month subscription to Nebula (I get no referral benefits) where LowSpecGamers video here and others are shared ad-free and with full benefits to the creators. Fight against the monopoly of YouTube.

But in our present moment, with the ongoing destruction of the United States' food inspection regime, increasing numbers of anti-trust frustrations against Amazon, the bread price-fixing debacle of LobLaws, and, most recently, a crusade against "greenwashing," questions of consumer protection and competition feel like they've reached their highest point of public salience in my lifetime.

And while perhaps seemingly trite in light of the United States' hostile economic agenda towards Canada and other trading partners, the salience of competition policy in particular becomes ever more important in an age of economic nationalism.

But let's go back to the beginning, first: where does all of this come from? And after that, where can it go?

The Ancient History of Trying to Stop People from Getting Ripped Off

If you take the terms at their literal face value, the idea of protecting a "consumer" goes back to the beginning of law. The Babylonian Code of Hammurabi (circa about 3,800 years ago) actually includes some surprisingly specific prescriptions around how commerce is to be conducted. In one example on the regulation of professions, the Code says that:

If a builder builds a house for anyone and does not complete it firmly, and the house that he has built collapses and kills the owner, then the builder shall be put to death.

Ever since then, both governments and private bodies, such as guilds, have all upheld various standards of practice to ensure that customers don't get taken advantage of. In many cases, as with the guilds, this was also tied up in protections for professions or particular types of goods, preserving reputations and sometimes market position, as well.

Modern consumer protection began with the Pure Food and Drug Act (1906) in the United States. It was hugely influenced by the work of advocate Harvey Wiley (1844–1930), a practising chemist who had a strong interest in scientific communication and public welfare. Wiley was the force behind the Act, but there were other American crusaders like socialist writer Upton Sinclair (1878-1968), and journalists like Samual Hopkins Adams (1871-1958), who were all part of a wave of agitation for protection of the public as mass-consumption of many goods now became possible.

Ramesh Sakunaveeti writes of this history:

As society embraced the benefits of [mass production of goods], consumers found themselves exposed to unprecedented risks and challenges related to product quality, safety, and the integrity of business practices. The realization dawned that an unregulated marketplace could lead to exploitation and compromise the well-being of consumers.

Leadership in this moment came from the United States, where a slate of other policies followed the Pure Food and Drug Act, culminating in 1914 in the establishment of the Federal Trade Commission. Suakunaveeti, again, argues that

"[t]he FTC became a pioneering institution, setting the stage for a more equitable marketplace by tackling deceptive practices and promoting fair competition. The influence of the United States reverberated globally, prompting other nations to recognize the importance of safeguarding consumer interests. In response to the evolving landscape of commerce, various countries began developing their own frameworks for consumer protection. These frameworks aimed to address the multifaceted challenges consumers faced, ranging from misleading advertising to substandard products."

Without giving a blow-by-blow history of American consumer protection and competition policy, it's fair to say that attention, energy, and resources towards these issues came in fits and starts. There were ebbs and flows from its creation afterward, but by the telling of FTC economists at a fascinating gathering in 2003, another major sea-change in the US came in the 1960s after a new generation of rabble-rousers in the 1960s and 1970s, typified by longtime consumer advocate Ralph Nader.

In the 1960s and 1970s, there was another burst of creative institutional energy, this time around the world: 1972 saw the US create the Consumer Product Safety Commission, but Japan had already created the National Consumer Affairs Centre in 1970, and even before that, different European consumer protection groups created a united Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs (BEUC) or what is now called the European Consumer Organization.

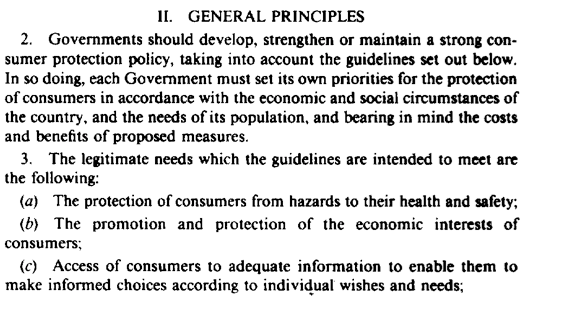

A global push on these issues culminated in 1985 with the adoption of the UN Guidelines for Consumer Protection (UNGCP), a set of legal principles about how countries should structure their consumer protection laws and policies.

With the Cold War nearing its end, many post-colonial and Soviet bloc countries were now in a position to take up on both past experience in the US, and a growing international consensus. Brazil's post-dictatorship 1988 constitution explicitly paved the way for consumer protection and in 1991 they ratified what is considered by some to be one of the more aggressive consumer protection systems in the world.

As Iris Benöhr wrote in the Journal of Consumer Protection in 2020, since the adoption of the UNGCP:

with the emergence of the digital era, the landscape has experienced dramatic transformation, and consumers have been facing an expanding range of challenges. Therefore, new provisions were introduced by the revised Guidelines in 1999 and then 2015 covering, among other policies, sustainable consumption, good business practices, financial protection, and e-commerce. Furthermore, other international organizations have increasingly become involved in the development of consumer protection, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank. [...] As a result, consumer protection has gradually transformed from being a mainly national topic to being a core supranational law subject.

To my eye, the most important achievement in the unfolding of this new era is the development of the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). In the simplest terms, GDPR creates rules for how consumers' data may be used by different actors online (from sales platforms to individual websites). The regulation has been one of the most significant regulatory developments of the 21st century, with copycat legislation around the world that mirrors it.

From the Individual to the Market

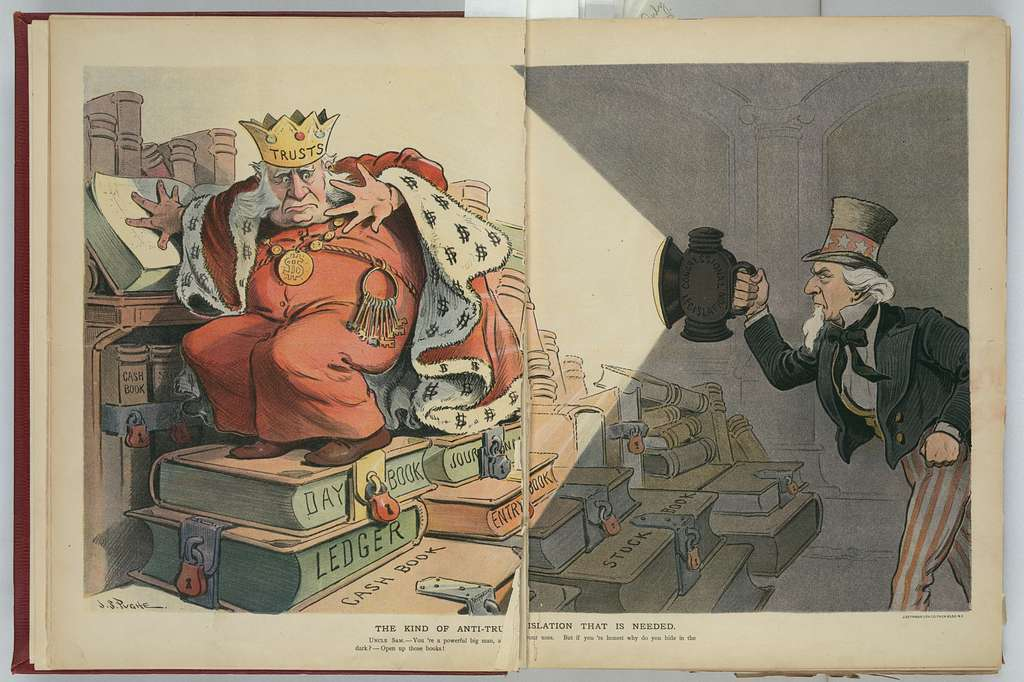

The modern origins of consumer protection are intimately intertwined with the idea of competition policy, where governments (try to) prevent the creation of monopolies, or at least moderate their influence where unavoidable (e.g., in energy utilities). The United States' Progressive Era, which saw the creation of the FTC and other institutions, was also the golden age of anti-monopoly (or "anti-trust") crusaders, among them US President Theodore Roosevelt.

In competition law, here Canada actually has a claim to fame: in 1889, the Dominion of Canada created what was the first ever-ever competition law, with the Act for the Prevention and Suppression of Combinations formed in Restraint of Trade, or, more simply, the Anti-Combines Act. Though the legislation had limitations, the central concept was to prevent unfair practices by a combine, a "merger, trust, or monopoly." This was in direct response to the protectionist National Policy of John A MacDonald, which had aimed to "protect" Canadian industry from American competition and promote the development of national industrial leaders who would, in MacDonald and others' eyes, "build the nation."

The original anti-combines bill was led by Conservative MP N. Clarke Wallace, which Brian Chiffins recounts it as initially a "reasonably forthright attack on combines. But after many amendments:

the legislation [was] clogged with modifiers, as it provided that one committed a misdemeanour if he conspired, combined, agreed or arranged, unlawfully, to unduly lessen competition in the production[.]

A year later, the United States passed the Sherman Act, which was their own take on fighting anti-competitive business practices. Cheffins views Sherman as "more decisive," as it stated that "every contract, conspiracy, or combination in restraint of trade which related to interstate commerce was illegal." And, furthermore, Sherman explicitly identified challenges to monopolies, which Anti-Combines did not.

However, both of these early laws were not terribly effective, and, though romantically attractive, even the ascendance of Roosevelt the first did not mark a true sea-change in how major corporations were dealt with. Chiffins, again, on Roosevelt argues:

Most corporations were left alone, and Roosevelt even granted informal antitrust exemptions to companies like International Harvester and U.S. Steel. A small number of "bad" trusts, such as Standard Oil and American Tobacco, were prosecuted, but the economic impact of these cases was minimal. Overall, the greatest impact of Roosevelt's antitrust policy was psychological. The bringing of the suits helped to diffuse opposition to large corporations. This was because some indication had been given that the American government could take action against big business.

The Laurier government would update Canadian legislation in 1910, with Justice Minister Mackenzie King following Rooseevelt's lead by focusing on negative publicity, rather than criminal action, to hold corporations to account.

Although Canada got its equivalent of the FTC in 1919, the Board of Commerce, there is general agreement that Canadian competition policy was ineffective until 1969. This is largely attributed to a favourable attitude to monopolies within Canada as an antidote to the size and power of American firms – and is something we struggle with to this day.

This raises an interesting point historically and geographically: Europeans, Canadians, the Japanese, and many other came later to the competition game in earnest generally after World War II. Sigrid Quack and Marie-Laure Djelic go so far as to say that:

"Until 1945, antitrust regulation was an American legal tradition with no impact beyond American borders."

Indeed, for many, Germany, Canada, and Japan to name three, large, capital-heavy integrated companies were desirable because of their purported efficiency and scale. That efficiency, in part, was felt to contribute to national power.

Following World War II, however, there was a burst of competition policy globally, with notable US influence involved:

- Japan got a US-imposed Antimonopoly Act in 1947, which was aimed to limit the power of the keiretsu, the large conglomerates, like Mitsubishi, which lead much of the Japanese economy.

- Germany's 1947 Act Against Restraints of Competition, like Japan, was also influenced by the US occupation, though it drew on some earlier thinking from pre-Weimar times.

- The UK had relied on a series of judge-made decisions about competition and, particularly during and after WWII, government-led price-setting. 1948 changed that with the Monopolies and Restrictive Practices Act.

- In 1952, the growing interest in industrial collaboration – with some pressure from the US around anti-trust – led to the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community, which included a focus on maintaining an internal but still competitive market within the members. This would eventually become the European Union.

Quack and Djelic, commenting on the American role in anti-trust policy, and its state now argue:

"Sixty years later, this has changed to a remarkable extent and antitrust is “going global." Today, close to a hundred countries have adopted a competition law and a transnational space such as the European Union is also structured by antitrust principles."

Canada's watershed moment came in 1969, when the long-established Board of Commerce was injected with fresh ideas and energy during the first term of Trudeau senior's government through the Interim Report on Competition Policy. Reforms were brought forward to increase enforcement powers on competition, but ultimately it took until 1984, with the Competition Act and the creation of the Competition Tribunal.

Catching up to the FTC and some other authorities, it finally provided enforcement and review mechanisms that went beyond the most egregious criminal proceedings. But after that, it remained basically unchanged until 2023, when the Trudeau junior government began bringing in new regulations, including a stronger focus on deceptive marketing practices related to claims about being "green."

From around 20 different national regimes in 1980, by 2009, over a one-hundred countries had now developed various forms of competition policy, first influenced by the United States, but also increasingly various European institutions, including eventually the EU. Even China, long the land of state-owned enterprises, took a 14-year journey that culminated in the development of the Anti-Monopoly Law in 2008.

When consumers and markets are both in danger

I mention consumer protection and competition policy together because I see them as different sides of the same coin: consumers lack the resources, generally, to fight companies about things they do outside of an immediate transaction, and smaller businesses (e.g., Amazon sellers) may get backed into a corner and treat customers poorly based on what the big guys do.

In many cases, frustrated consumers have only had the last resort of litigation to get what what's fair. The challenges of this kind of approach, while not strictly consumer protection, are exemplified by the American case of Stella Liebeck suing McDonald's. After getting third-degree burns on her legs after spilling coffee, she won $640,000 in damages. She, and the case, however, were vilified for what was deemed a frivolous lawsuit, with a helping-hand from McDonald's corporate communications.

Since the 1990s, with the development of online platforms and the increasing crisis of climate change, things have only gotten more complex. In 2004, and then 2015, the United Nations had to update its consumer protection guidelines around sustainability and online commerce in direct response to these.

These challenges have only grown more intense since then.

Protection and Competition for Sustainability

While the UN came up with consumer-oriented guidelines around sustainability in 2004, enforcement against companies making unproven, misleading, or false claims about how sustainable their products were (i.e., "green-washing") was extremely lax. Unfortunately, the problem's only grown since then.

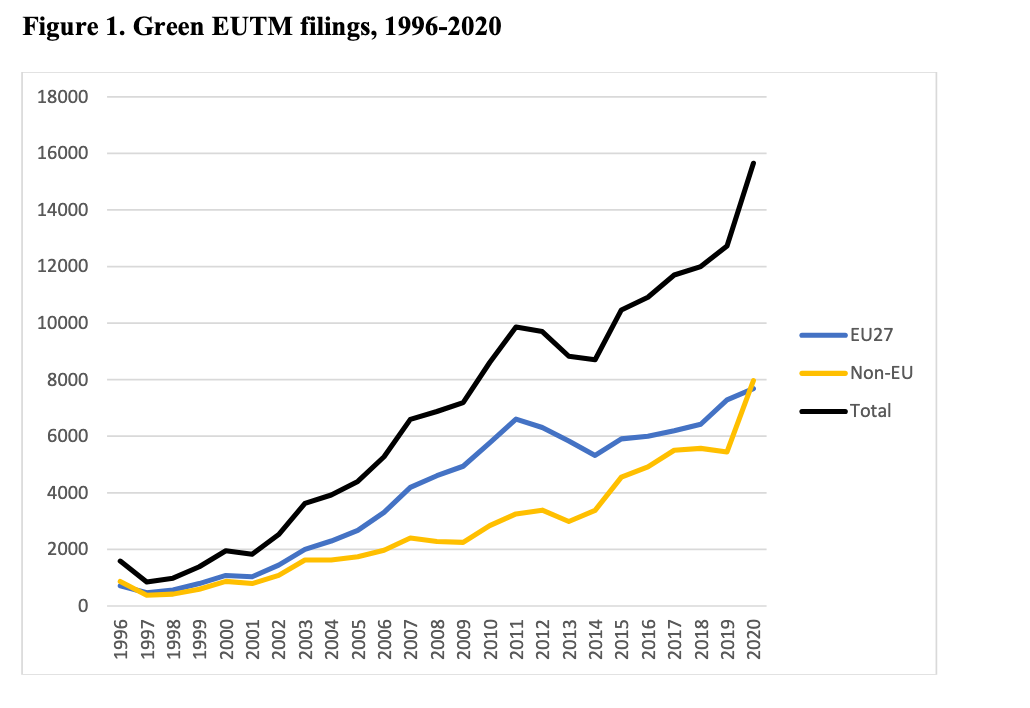

In 2021, the EU Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) released a report that looked at 2 million EU trademark applications with some sort of sustainability claim made between 1996 and 2020.

In research also released that year, a global sweep in coordination with the EU, the UK, and other markets looked at how many of these increasing numbers of green claims were misleading, or outright false.

For the EU specifically, they found:

- In more than half of the cases, a business did not share enough information for a consumer to judge claims' truthfulness.

- In 37% of cases, the claim included vague statements such as “eco-conscious”, “eco-friendly”, or “sustainable” which conveyed positive environmental impact without any empirical backing.

- In 59% of the cases, a business had no readily accessible evidence to support any of their claims.

The impact of this mismatch between big claims and no backup has been palpable on consumers.A 2023 Deloitte survey in Canada found that 57% of Canadians don't trust companies' environmental claims.

In one example, Shell's "Drive Carbon-Neutral" campaign was put in the cross-hairs for breaking consumer protection law because of the way it claimed that its fuel had been entirely offset. In reality, it was almost impossible to verify if this was the case and those offsets that had been purchased were of dubious quality.

With heavy-hitting consumer protection and environmental lawyers weighing in, and following on work in the EU, in 2024 the Government of Canada began to start to change the Competition Act to better handle major environmental claims by companies. This continues to be a major frustration to Canada's oil companies in particular, who felt that they were being unfairly targeted in having to provide more specific evidence to their claims about climate action.

Platforms as Power

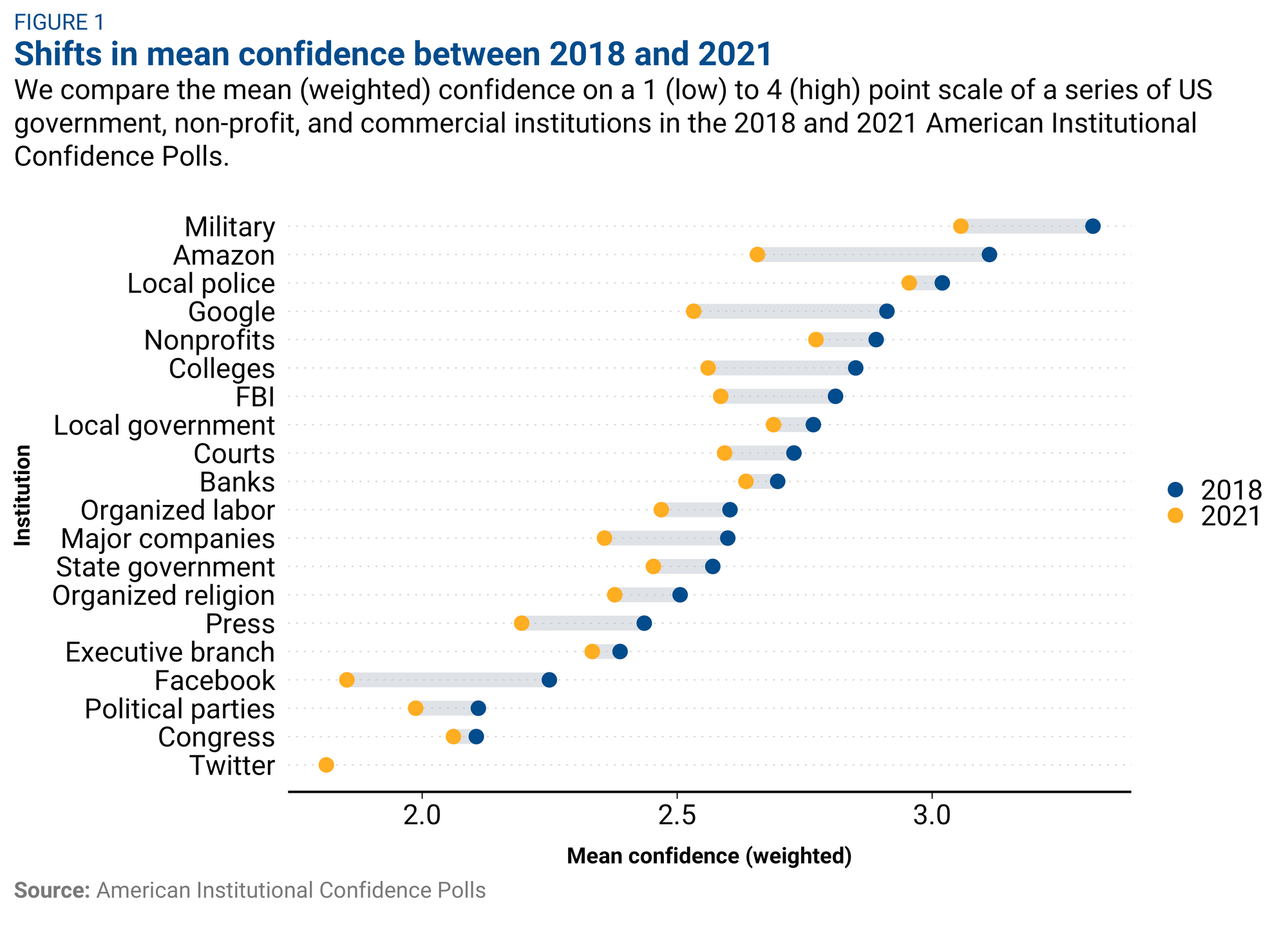

From incredible popularity in the early 2000's, "big tech" is now generally un-trusted. Polling in the 2020s, particularly after COVID-19, has shown a continuing downward slide for peoples' trust in these larger platform companies – with companies like Facebook and Twitter particularly under the gun.

In 2024, Gallup showed that big tech had fallen to having the trust of just 27% of the American public, below organized labour (29%), the police (51%), and small businesses (68%). With the recent behaviour of Twitter-owner Elon Musk, this may decrease yet more (though, interestingly, people hate Zuckerberg more).

Much of this is because of the (rightly) perceived interference of American tech companies, especially social media and search engines, in politics. But even before COVID, cracks were showing.

In 2017, a Yale Law student and anti-monopoly researcher, Lina Khan, wrote a paper for the student journal on the "monopoly paradox" of Amazon. The article is, to say the least, intimidatingly good. And it's no surprise that, a short five years later, Khan was appointed the Chair of the Federal Trade Commission (remember them?).

Khan's analysis was and is elegant and resolute:

the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competition to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the architecture of market power in the modern economy.

She argued that a platform like Amazon created new types of market effects that the traditional focus of consumer protection (keeping prices low and purchase-practices fair) wouldn't necessarily interact. Amazon would make it easier for a consumer to buy things, and help make prices cheaper - but its power between consumers and sellers on its platform was what should actually be most worrying. As she says in the abstract:

because online platforms serve as critical intermediaries, integrating across business lines positions these platforms to control the essential infrastructure on which their rivals depend. This dual role also enables a platform to exploit information collected on companies using its services to undermine them as competitors.

Amazon, however, is only one among many platforms at play. Simon Digby does a great job laying out the larger story across the other major tech players.

MediumSimon Digby

MediumSimon Digby

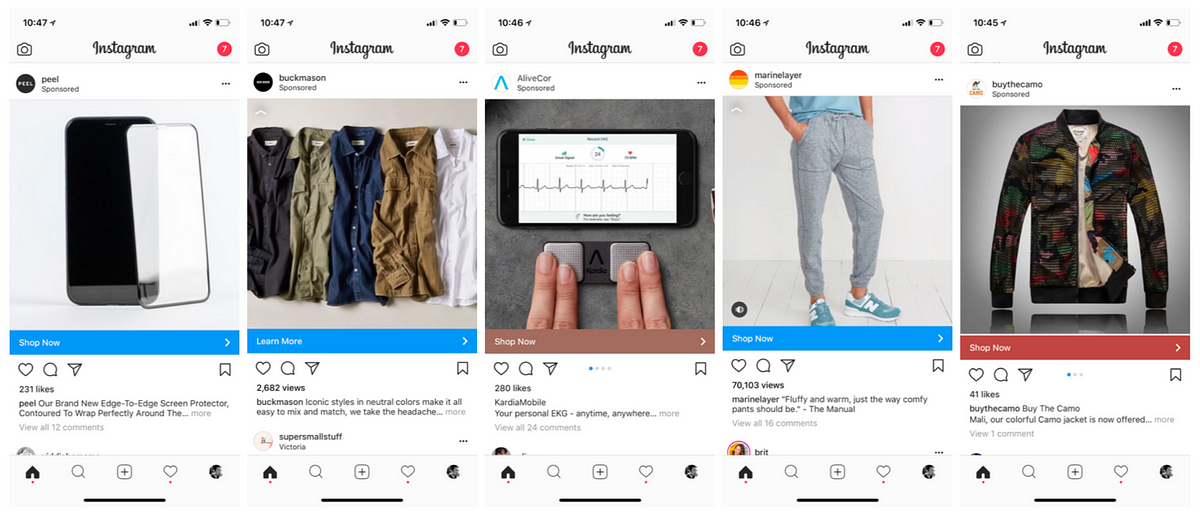

As Digby argues, major ad business players like Facebook and Google actually detract from consumer welfare in two distinct ways:

- By "limiting consumer choice" in what's sold or advertised on their platforms.

- By consolidating the digital advertising industry overall (Google and Meta, for example, held 28.9% and 19.4% of all global digital ad revenue in 2024)

As Digby pulls from Scott Galloway's The Four: the Hidden DNA of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google (quoting via Digby):

Amazon is going underwater with the world’s largest oxygen tank, forcing other retailers to follow it, match its prices, and deal with changed customer delivery expectations. The difference is other retailers have just the air in their lungs and are drowning. Amazon will surface and have the ocean of retail largely to itself.

For all of these reasons, Khan, during her term as FTC Chair, went after tech in a way that the US government had never really done before. The biggest push was a joint case against Amazon by the FTC and 17 state attorneys general. There's a trust-busting ring – and many echoes to Khan's 2017 article – to the case they put forward:

Amazon violates the law not because it is big, but because it engages in a course of exclusionary conduct that prevents current competitors from growing and new competitors from emerging. By stifling competition on price, product selection, quality, and by preventing its current or future rivals from attracting a critical mass of shoppers and sellers, Amazon ensures that no current or future rival can threaten its dominance. Amazon’s far-reaching schemes impact hundreds of billions of dollars in retail sales every year, touch hundreds of thousands of products sold by businesses big and small and affect over a hundred million shoppers.

With the Trump Presidency, it is not clear to me how the case will proceed – even if the FTC pulls back, or even out, the state attorneys general could conceivably continue to bring this (or a new) case forward. Trump notwithstanding, it is unlikely we've heard the last of anti-trust legal action in the US, or elsewhere.

Building the Right Kinds of Walls

Donald Trump's economic warfare with Canada, Mexico, China, and likely soon to be others, has a strange echo of days gone by. Heck, the founding of the original Canadian confederation was largely based on the desire of certain elites to escape the economic dominance of the United States – and tariffs and protectionism via the National Policy were part of the recipe.

But despite rhetoric that sometimes feels out of the 1930s, or even the 1830s, the world of today is much different than many leaders would like it to be. Our economies have become vastly more interconnected and in ways that go beyond "I sell you peaches and you sell me nails." Cars cross the Canada-US border six times before they're ready to sell to consumers. As I talk with my colleagues about a lot lately; even a "made in Canada" heat pump involves components, down to the screws, that come from all over the world.

And we're not just talking about trade – every facet of how our economies works today is more complex than it's ever been.

In 2024, Amazon had 9.7 million retailers (though not all were active) on its platform. But despite that number, it's not like Amazon is just a big market with millions of stalls. Retailers can both sell and ship directly to a consumer, or choose to do what's called "fulfillment by Amazon," which means that the platform both stores and ships the product – for a fee.

Further complicating the story is the fact that, 34% of Amazon sales in 2024 were led by "drop shippers,." Drop shipping is when companies advertise a product that they don't make, or have any of on-hand, and then go call a real manufacturer to get the product "just in time" when they get an order. The practice was industrialized by Amazon itself, but there has been a whole ecosystem of smaller sellers doing it since – often to the detriment of new entrants and many consumers.

Positive SlopeScott Belsky

Positive SlopeScott Belsky

So where does this all leave us?

How do we protect consumers from getting taken advantage of?

How do we prevent monopolies from unfairly putting their thumb on the scale of commerce?

What does it take to have a good economy?

We Need Courage – and Capacity

While we know that Roosevelt the "trust buster" was more interested in public shaming than legal or policy action, his rhetoric was important in shaping a public consensus on the need for competition. It gave political justification for many other work that would eventually follow, including the FTC and individual enforcement actions.

While there were innumerable ebbs and flows of action to protect consumers and the market overall from graft or monopolism from then, the foundation built in the early 1900s is still beneath us, whatever its cracks and stains may look like right now.

The structural metaphor here feels particularly apt: we are the inheritors of a vast institutional wealth.Systems created for our benefit (always imperfectly), are like a grand old house that is in need of serious renovation.

The simple story is that most were created post-WWII, were injected with greater mandates, resources, and focus in the 1960s and 1970s, struggled under de-regulation and de-prioritization from the 1980s to 2010s and now have a profoundly uncertain future. Despite the fact that there being more diverse ways than ever that consumers can be taken advantage of, and that major monopolies are hurting the fairness and transparency of commerce between businesses, there are still ongoing debates about the best pathway forward.

There are many arcane arguments about the specifics of what to do in any number of cases, such as greenwashing, or digital commerce, but they all rest on a more foundational premise: the capacity of government (and related actors) to do the work.

This question of "state capacity," was brilliantly highlighted by the US-based Niskanen Centre this year.

Niskanen Center - Improving Policy, Advancing ModerationJennifer Pahlka

Niskanen Center - Improving Policy, Advancing ModerationJennifer Pahlka

.

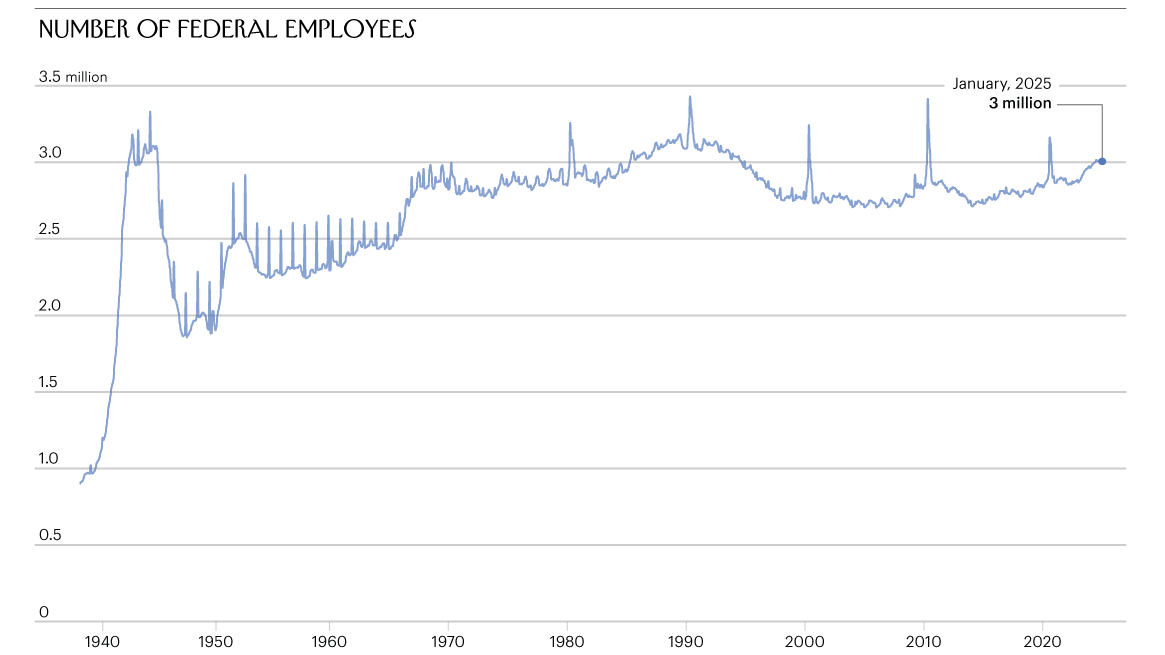

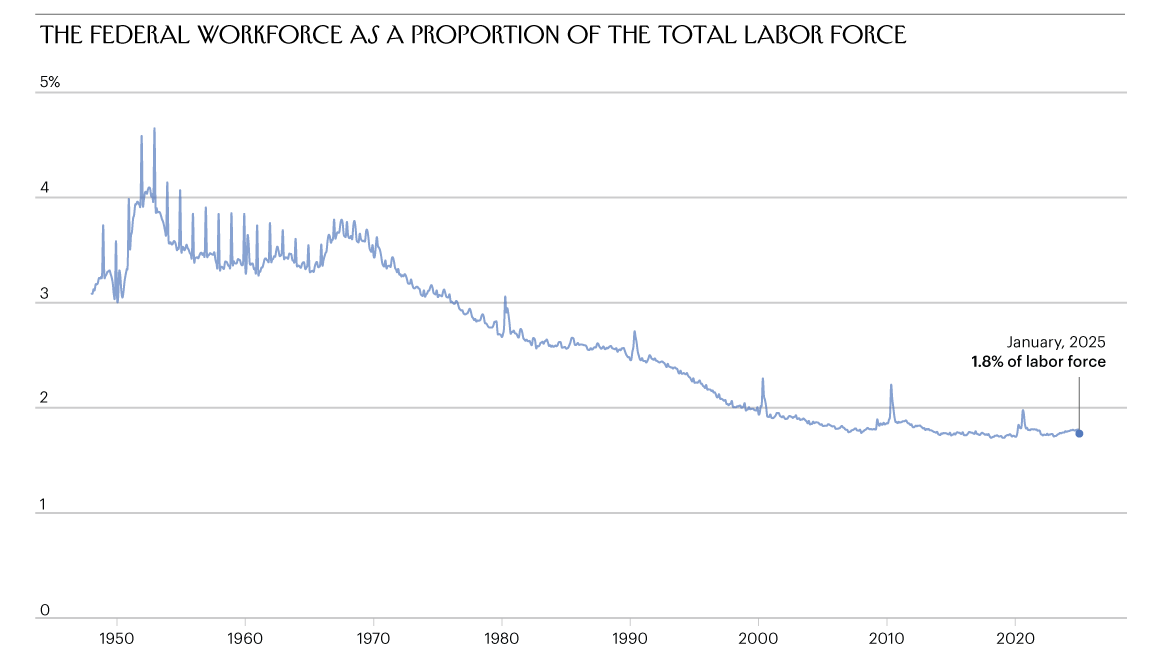

As a recent New Yorker story laid out in the context of Elon Musk' maurading, the United States' federal workforce hasn't grown since the end of World War II.

Indeed, its gotten steadily smaller on a per-capita basis since then (to 1.8% of all employment in 2025).

This is hard to track globally across service areas, but as we all feel personally in healthcare, this is true at least in critical segments of the economy that we rely on the government for. Again, US data is easier to come by, but the efforts of the Biden administration to increase the number of auditors and tax collectors at the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) meant that the US Government brought in hundreds of billions of new revenue just because they had the people to collect it.

What I like about the Niskanen paper, which I feel mirrors in some ways people I've written about before, like "mission economy" proponent Marianne Mazucatto, is that we both need governments with more resources, and we need them to think and act differently.

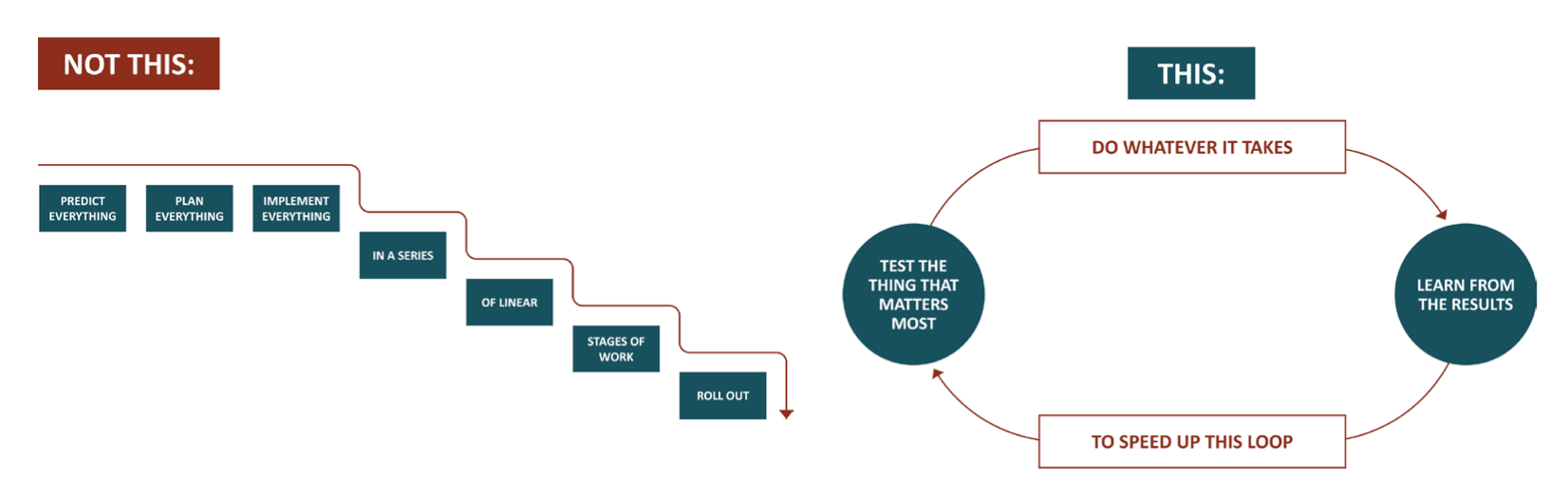

They reference Andrew Greenway and Tom Loosemore's call for government to move from a "waterfall" model to a more results-driven government that's adaptive and flexible, always focused on the ends and changing its means to get there effectively.

I could (and will, someday) write at length about all of the twists and turns of what this means. It is not the case that government is just bad at stuff, either. There are innumerable considerations to bring into how to operationalize the above principles, but at the core of this, there is a meaningful reckoning with the history of government, the opportunities technology is creating for us, and the new and different needs of our society. We should be having this conversation Every. Single. Day.

Assuming we really want to invest in our capacity to solve big problems, the specifics of what we need to do then flow naturally from there (ideally with the aspect of the above mindset integrated). The big-ticket items are actually relatively elegant and intuitive to all of us:

- Don't let the big companies get too big – and, where needed, break them up.

- Make decision-making easy for consumers. I'll come back to greenwashing in another post, but another favourite example of mine are those annoying 30+ page end-user "agreements" we all scroll through to get to use an app or software. These should be written in plain language.

- Enforce punishment against bad actors, especially the biggest ones, proportionately and publicly. Stella Liebeck died a broken woman after the public vitriol directed at her - both McDonald's and the media should never have been able to get away with how she was treated.

- Bring the public (and workers) in to help make decisions more collaboratively, while still drawing on experts to get the details right.

It's easy to think about everything I've said above as a "pocketbook" issue, about saving individuals or businesses a few dollars or some inconveniences here or there. But these questions are much, much bigger.

If we can't trust what each other say (whether that's in business or otherwise), and the functioning of our brains and emotions are being manipulated for others' profit, then our very freedom is in question.

Humans have grappled with these questions since the dawn of civilization, and, in my view, we got pretty good at dealing with them in the past hundred years or so. We need to learn from that, and build on it.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.