There’s something imperceptibly quiet about the kind of of city that Chicago is. Perhaps it’s the fact that Chicago is such a large urban centre in North America, and yet its status as an almost-megacity is rarely reflected on by folks from the West Coast like myself. Having seen it now, I am beyond embarrassed for my oversight of this incredibly rich and fascinating place. I consider this little missive as part love-letter and part apology for that accident.

I have tended to think of Chicago through three lenses:

Firstly, as a centre of the city beautiful movement, and a hotbed of all of the kinds of politics (radical and reactionary) that emerged in the United States at the turn of the 19th century.

Secondly, as one of the American cities wrestling with inequality and racial divides in a visible and sadly often violent way.

Finally, and related to the former, is that I think of Chicago as the site of the political awakening of Barack Obama, and a laboratory for some of the key issues and approaches that he developed and later brought to the United States as a whole.

As neat as these categories are, they really belay the fact that Chicago has not been a frequent reference in my thinking about urbanism or politics within North America.

The whole idea of writing ideas on the city down is that I want to not only capture my impressions, but demarcate what seems like yet another fascinating source of politics, ideas, and energy in the North American milieu that I want to be much more attentive to in the future. Not just because of the area’s size — I cannot seem to stop reflecting on the fact that there was another megacity resting in the middle of the continent that I was not paying attention to — but also because it seems there is something happening there that is worth paying attention to.

Impressions

What follows is a thematic sectioning off of things that stood out to me most in the city. These are hardly encyclopedic and reflect time that was mostly spent in the centre and northwest of the city, but I hope are still of interest and relevance to others. In organizing my thoughts around the city, there were three ways of viewing the city that seemed most fitting to organize my impressions in, responding both to history and things that observationally were most confronting: beauty, inequality, and futurity.

Chicago the Beautiful

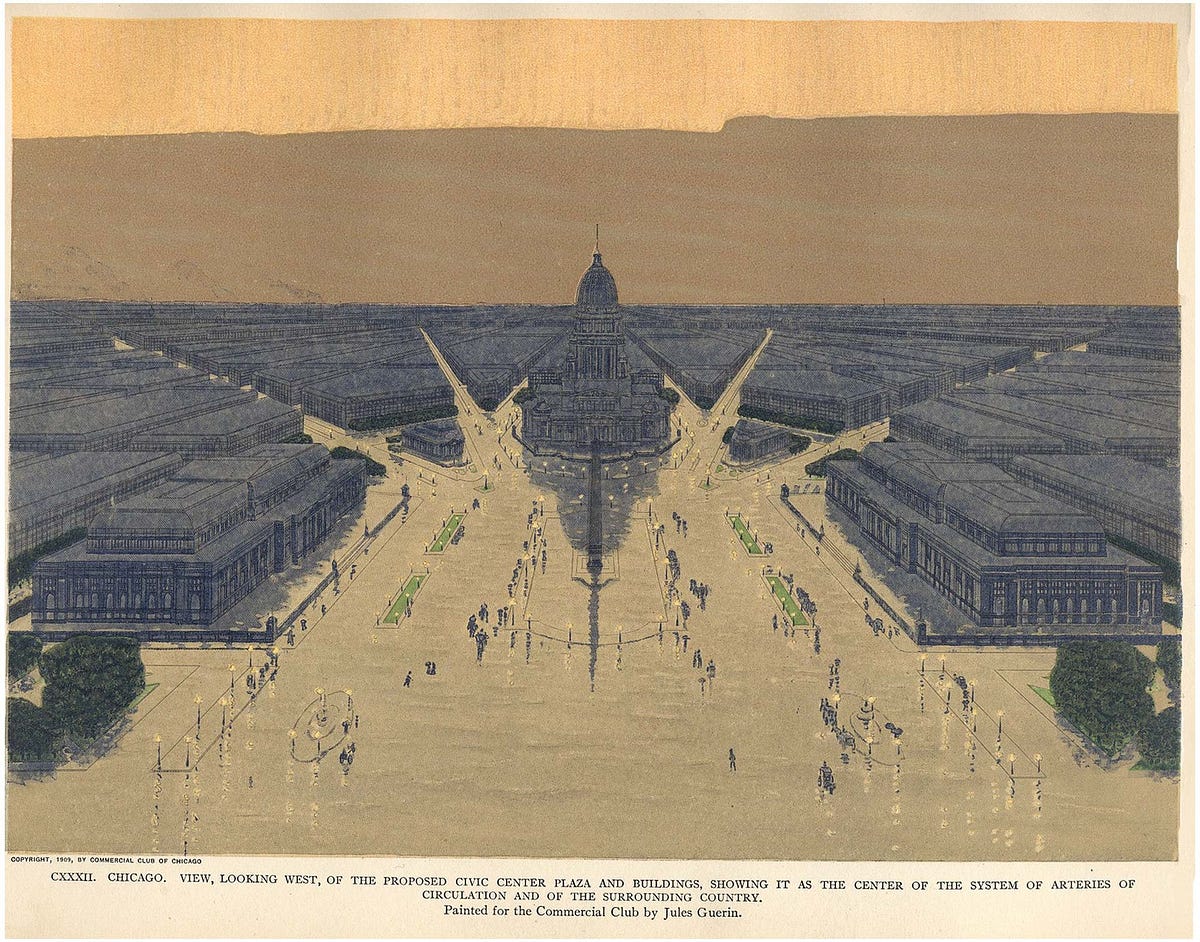

It’s hard to imagine becoming a planner in North America and not learning about the Chicago of the late 19th century. The Columbian Exhibition, the Great Fire, the ‘City Beautiful,’ the Burnham Plan; red-lining, white flight, and public housing. Any one of these themes are critical to understanding where city building has gone and what it must contend with today, but that each of these are paradigmatically represented in Chicago was definitely hit home to us in school, and became readily apparent when you see the Burnham Plan’s lasting legacy on the city — wide boulevards, incredible lakefront parks, opulent civic buildings.

While I was taught that the Chicago of the 1960s onwards has been plagued by numerous crises and challenges, including immense racial unrest, economic inequality, and a painful process of deindustrialization, it is clear that Burnham’s vision of grandness still holds tremendous sway in the cultural vision of the city itself.

I get the sense that many contemporary urbanists in Chicago are more interested in unpacking the racism and classism that underpins much of the planning of this era (and as we are certainly doing in Vancouver with figures Harland Bartholomew), but that ever-seductive idea of “making no small plans,” still appears to underpin initiatives like Millennium Park and the new (and beautiful) 606.

Myself and everyone I travelled with were struck by the beauty of the of these assets and their longevity . Despite the many flaws of American urban finance and infrastructure renewal, these civic assets appeared to have been lovingly maintained, and there was a strong sense of pride that I felt emanated from all Chicagoans about the beauty of so much of their city. Vancouver, as a city that is so often known for the beauty of its surroundings, could learn a thing or two from a place that spends so much of its public space on the public good, and at such a grand scale.

Chicago the Unequal

At the outset, I’ll say that much of my trip was centred to the wealthiest parts of the city. I’m conflicted about this for a variety of reasons, since I think that truly taking in a city means seeing all of its parts, but I’m also conscious of not perpetuating ‘ghetto tourism.’ In the absence of someone to introduce me to these parts of the city, we hewed to some of the more tourist-oriented areas and rapidly gentrified areas, like Wicker Park.

That caveat offered, it was still apparent to me that Chicago is on the front lines of battling inequality, in both new and old forms. To Chicagoans, perhaps this feels like a perennial battle, thinking back to its continental significance in labour activism and social democracy. Walking through what was once “the Jungle” and seeing posh loft apartments on every corner is a very affecting experience. Looked at through different angles, it is variously cynically ironic, economically productive, and, in global design terms, rather banal.

I offered on Twitter that Chicago looks and feels like it’s fighting this battle, and in some ways, losing it, across most of the landscape of the city. The beautiful Millennium Park, and certainly the 606, feel like big, bright billboards for Floridian campaigns to attract young people and “creatives” even at the same time as they are beautiful works of fun, accessible urbanism. The intermingling of panhandlers, some of them very adept local guides and almost all of them black, with tourists (myself included) looking for the ideal selfie, is emblematic of the kind of interstitial zone that global centres of occupy — wealth and poverty intermingling in a public display.

Two physical facets of the landscape made this battle particularly affecting: the placement of washrooms and the experience of the streetscape.

The downtown core, both north and south of the river, is a vast desert of this crucial amenity. Parks that thrummed with the movement of tourists on segways and merchants offering snacks and kitsch. And yet despite all of the standard identifiers of the modern, connected city — free public wifi, a thriving local bike-share, and Trip Advisor-approved tours — there was never a bathroom to be found anywhere. Starbucks, my standard semi-public washroom in a pinch, had numerous locations downtown that simply did not have them (an observation that immediately made me curious about code requirements for ground-floor retail). Based on my anecdotal experience, the vast majority of the retail locations I went to downtown did not have washrooms — those that did almost exclusively also had keys or key-codes. In general, my observation was that, in contrast to Vancouver and places like it, the disciplinary functions of architecture were far less subtle and meant to communicate quite clearly that the poor, the homeless, and anyone else deemed undesirable, were not welcome there.

On a larger scale, the streetscapes of the city also communicated this message similarly, though through different means:

It feels unfair as a Canadian to dunk on American cities for the poor state of their roads and sidewalks. There are massive, federally-created structural fiscal disadvantages to the maintenance of American infrastructure that are not any one city’s fault. We should decry unfair property tax regimes and the criminally low federal gas-tax alike, but with all my love to this great city, we should also recognise that like so many North American cities, Chicago streets are car-centric battlefields for pedestrians. In addition to the immediate experience of safety, or the impacts of pollution, there has been much written about the use of highways to segregate and cement the redlining of cities like Chicago, and while I am no expert, I have heard and read more than a little as to how this particular infrastructure type was devastatingly weaponized from the 1950s onwards.

Medium user Tomasz has a impactful account that outlines the painful and often explicitly racist outcomes of this work. To quote from him directly:

Chicago’s leaders saw the building of expressways as a way to “clear slums” and further segregate black and white communities. While connecting suburbs to the city, expressways went through black communities, physically separating them from white communities.

[…]

It was environmental racism not only against the African American community, but also against European “peasants,” e.g., Italian, Greek, Polish, and Jewish immigrants, as well as Mexican and Chinese immigrants, who were also displaced by the building of Chicago’s expressways.

The highway system tells this story in historical terms, and where we had the opportunity to travel between some of these highway-designated districts, the racial divisions were very clear. And yet, the finer-grained experience at street-level also adds a modern twist to this with ride-hailing.

If you follow me on Twitter, you know I am continuously aghast at the danger that we put pedestrians and cyclists in every day on our roads. Design ignorance, corporate greed, and ingrained cultural biases towards big, fast, and dangerous cars means that walking on the street is to quite literally play dice with your life. Nowhere in recent memory have I felt this more acutely than with Chicago’s car culture, particularly with ride-hailing. Uber, Lyft, and other services are omnipresent throughout the city. The safety challenges and the disorganization they cause are crushing livability in the city. Parking on sidewalks, unannounced u-turns, randomized pick-ups mid-street, and lazy, crosswalk straddling stops were practically incessant. Even in tech-addled San Francisco, I don’t know that I ever saw quite this entitlement of drivers.

The starkness of wealthy, often white, denizens of these ride-hailing services, expectantly waiting for their drivers, generally people of colour, to race through lights, cut through bike-lanes, and otherwise endanger others was frightening, to say the very least. From a more systemic vantage point, I think it is emblematic of the central battle of 21st Century cities around who owns our common spaces. Chicago is fighting on numerous fronts on racism, on environmental justice, and progressive city-building, but in the case of roads, it feels like there is much, much further to go.

Chicago the future(?)

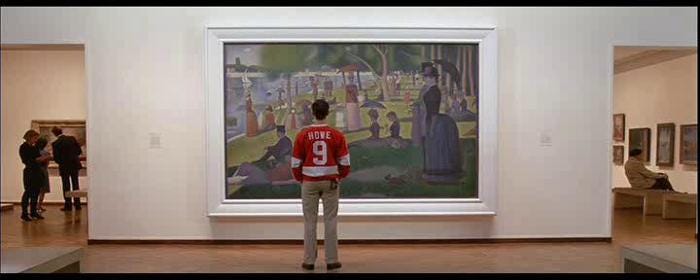

Looking at Millennium Park today, or the 606, for that matter, Chicago looks and feels so much different than the images I saw in gritty crime dramas, or even in the loving views of John Hughes.

Chicago is muscularly staking claims to great architecture once again with Aqua and the impact of local architects can be felt as far away as Riyadh as the local Trump Tower influences the development of tall buildings around the world.

Politically, the city feels electric and alive with something interesting, though no doubt financial and racial struggles are a bitter soup to swim within for many locals. The election this year of Mayor Lori Lightfoot, the first black woman and only LGBTQIA mayor to lead Chicago (and, along with a new wave of women mayors, a huge move in the right direction for US mayoral politics) and the concomitant removal of preeminent Obama staffer, Rahm Emanuel, and the continuing struggles over transportation, schooling, and racial justice in the city all give me strong reasons to stay in tune with what is happening there — I hope to derive lessons that have applicability back in Vancouver and Canada, particularly with regards to racial justice and economic restructuring.

Like many cities, I see Chicago facing the tripartite headwinds of economic inequality, technological transformation, and environmental decline (particularly climate change).

I think the City has a rich tradition of activism, from labour to racial justice, that means that many, myself included now, have to look at the city to understand how to build safer, more equitable communities that protect and provide restitution to the historically marginalized, particularly black communities and immigrants. And yet, the very reason for this tradition is that Chicago is one of the most segregated and unequal places in the entirety of the United States and has been on the front-lines of fights for racial and economic justice since colonization. How this knowledge is mobilized to face contemporary iterations of inequality, I cannot say — but I will watch with respect, interest, and solidarity.

As a planner, technological changes generally interest me most in how they manifest in the physical and social landscape. I saw and heard much abuzz in the city about its work on ‘Smart Cities’ technology, and it was clear that huge infrastructure investments were ongoing throughout the city, but to what purpose and for whom these investments are for are clearly unsettled contentions. As ever, I remain deeply uninterested in boosterish claims of how more sensors will save our cities; the seeming directionless application of new technologies in service of purportedly public, but generally in effect private, ends leaves me frustrated and cold. Chicago appears already caught in that current, but maybe there are some stronger swimmers yet to step into local leadership.

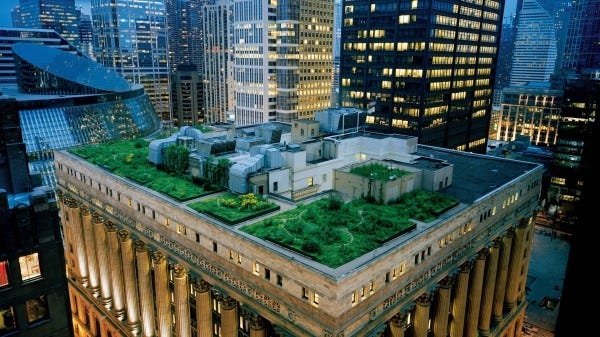

Finally, it would be uncharacteristic of me not to consider climate change and its impacts on any city that I visit. Chicago was no exception. With its wide-streets, ubiquitous car-culture, grand parks, and proliferate green roofs, Chicago’s sustainability was a complex system for me to parse. Both its historical and contemporary urbanism and growing focus on densification, green buildings, and mode-shifting, suggested to me that the city takes the threat of climate change seriously, at least at a high-level and wants to make investments to address it. But it was also clear that from the continuing investment in highways, the waste removal culture, and the (admittedly surface) conversations I had with Chicagoans, that there is still much in sustainable urbanism that must be digested in the city. And in their defence, with some of the other, seemingly more immediate, challenges the city faces, in terms of inequality and aging infrastructure, I can appreciate why this issue does not rise to the top of political consciousness — I only hope it does with enough time to act decisively.

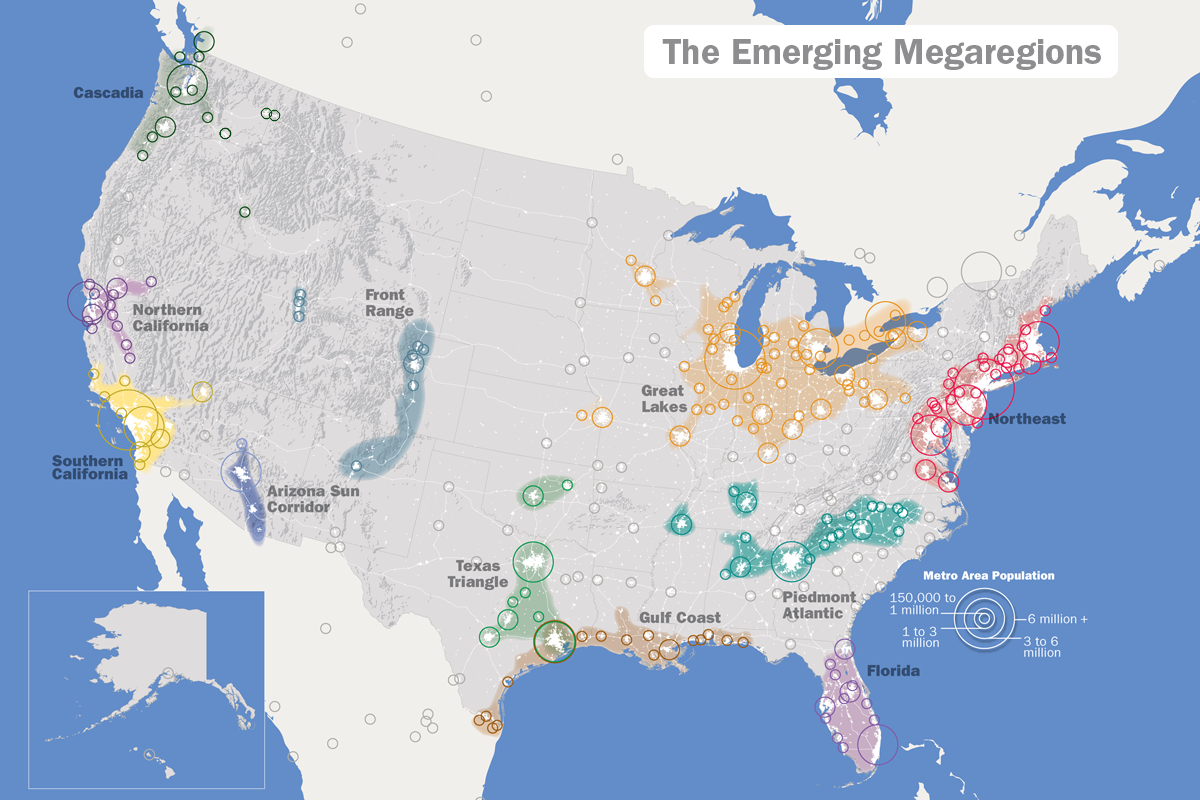

I was unfamiliar with the term prior to arriving, but the idea of a “Third Coast” feels more relevant now than ever for both the United States and Canada after seeing Chicago. As opposed to the narrative of inevitable decline inherent in “the Rustbelt, the very idea of Third Coast, or Inland Coast, or whatever you’d like to call it, was a powerful reminder to me of the stumbling economic and political power that exists within this region. Having been involved with conversations about Cascadia and the potential linkages between Vancouver and Seattle, I immediately became curious about shared Great Lakes urbanism.

From what I can gather, the linkage of major Great Lakes cities feels far less developed than what we have in Cascadia. But the potential, particularly with the incredible growth of both Toronto and Chicago (expected to a “megacity” by 2030), makes me feel that this region is one that will very likely take a much larger role in defining what our great cities and communities will look like. From what I saw there over the past week, I’m excited what they’ll bring to the table when they do.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.