Everyone's talking about energy these days. What was once an arcane topic for the particularly geeky, now regularly comes up conversation at the dinner table and on the street. People understand that, whether as a result of climate action, the huge surge in energy demand from digital living, or simply aging infrastructure, we all need to better understand and plan for the future of our energy system.

And while the desire for this conversation is excellent, generally speaking, the amount of fear I hear from people around the topic is deeply concerning.

Misinformation is everywhere, from fears that BC is headed toward imminent rolling brown-outs, to ones that the government is going to forcibly remove gas from existing buildings, or shut down small industries like brewing to somehow conserve energy or zero-out our carbon emissions.

And while a lot of that misinformation is deliberately being created by bad-faith actors, the discourse does accidentally stumble into a higher-level truth. There is a generally low level of literacy on what our energy system looks like today, and what it can – and could yet – look like in the future.

In this series, I hope to shed some light on these topics, particularly in light of the upcoming BC election. In this first part, I'll focus on answering three questions:

- Why does the energy transition matter at all, particularly as it relates to climate change?

- How do transitions involving major changes in technology and society happen?

- What can citizens and communities, especially through their governments, do to shape both the process and the outcomes of these transitions?

In later parts, I'll talk about the past history of BC's energy system, and end with the current and future state of infrastructure and policy.

What you need to know

- We need an energy transition because our current system - mostly burning things - is highly inefficient and, through this inefficiency, creates planet-warming pollution (which is bad).

- We don't need to replace fossil fuels 1-to-1 as we transition to renewable energy. This is because we're not just swapping energy sources, we're also increasing the overall efficiency of our system.

- All technological transitions in general are messy and involve both the fallacies of human perception via hype and overestimation, and our ingenuity at learning how to do things better over time

- The public can play an active role in making these transitions both fair and orderly through a deliberate approaches like "market transformation."

Why an energy transition?

The primary reason we want to change our energy system is that the primary source of our energy today (fossil fuels) produce waste gases which trap more heat on the planet than we and our systems are used to.

We call this heat-trapping phenomena climate change, and, as oil companies have known for 60 years, it is bad for humans and all other life.

Because fossil fuels are so immensely profitable, you'll hear a lot of explicit and subtle pushback on the idea that we need to move past their use. One of the most common refrains of those disagreeing with the need to change, is that our energy system has gotten better as it has come to use "denser" forms of energy, like oil or gas, instead of less dense ones, like wood or coal. From this perspective, we already have made the most important energy transition: for every ounce of stuff we burn, we get more energy than ever before.

This makes sense if you're grading on a curve. Compared to our ancestors in the 1500's, yes, our system is vastly more efficient than ever before. But as Nick Eyre and later the team at the Rocky Mountain Institute have written about very recently, we need to move past this backward-looking outlook.

Both papers are amazing and worth reading in full, but both can summarized in a few key points:

- Burning stuff ("heat energy") loses 50-60% of the energy it starts with and, through the pollution of those losses (greenhouse gases), causes climate change.

- Electrical sources of energy ("work energy") are much more efficient, and only lose about 30% of the energy that they start with, saving money and virtually eliminating planet-warming pollution.

- Because burning stuff is so inefficient, replacing heat energy with work energy means you don't need to do it 1-to-1. (people who insist on this are falling into the "primary energy fallacy.")

How do technological transitions happen?

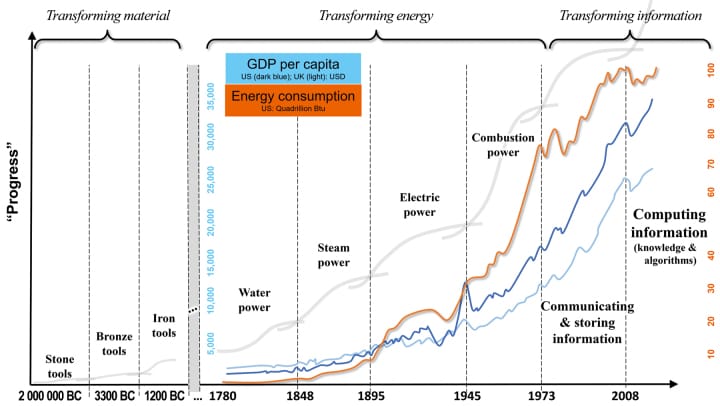

Human society has gone through many, many different social and technological transitions in its history. They can be hard to spot in the moment, but in retrospect we often refer to them as a "revolution" – like the ones in agriculture, steam, and telecommunications – because of how transformative these technological changes end up being for human society.

At the scale of the above graph – 2-million years – these revolutions look like a nice steady progression in human flourishing, but the reality of being amidst a given revolution is far messier.

I think of this messiness as having three dimensions, one about perspectives, one about material progress, and one about intention.

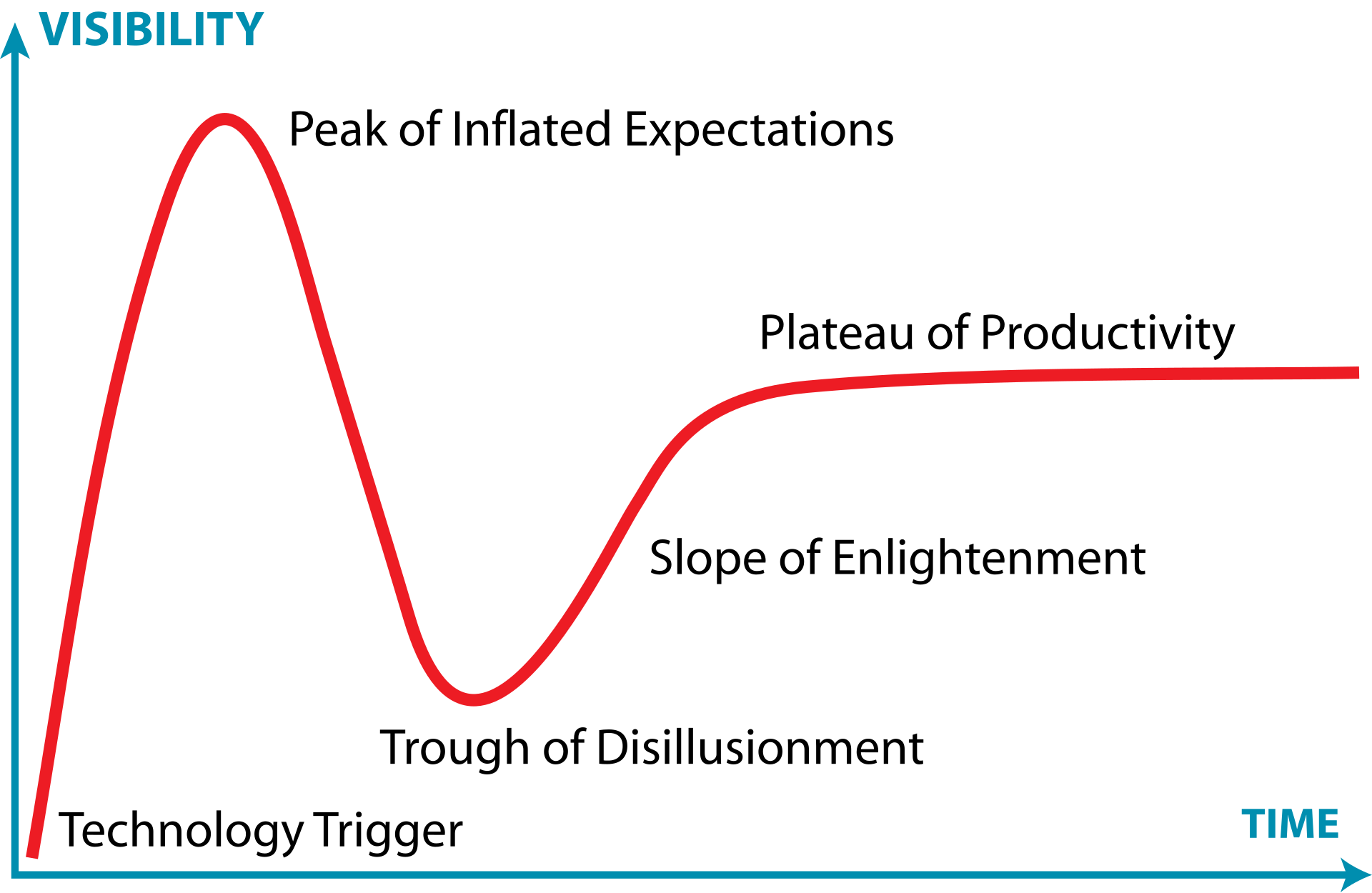

In terms of the perceptions of new technologies, almost all of them go through a process the consulting firm Gartner defined years ago as the "hype cycle."

Through their many years of consulting with technology companies, they said that technologies will go through five stages that involve initial excitement, a "peak of inflated expectations," a period of disillusionment, and eventually a settling into a "plateau" of generalized use and productivity once people understand how and where a solution can be effectively deployed.

If the public and especially decision-makers understand this hype cycle then they can be careful not to be lead too far into fantasy or pessimism as a technology evolves.

While our perceptions of technology have significant ups and downs, the material progression of a technology can be (though is not always) more linear.

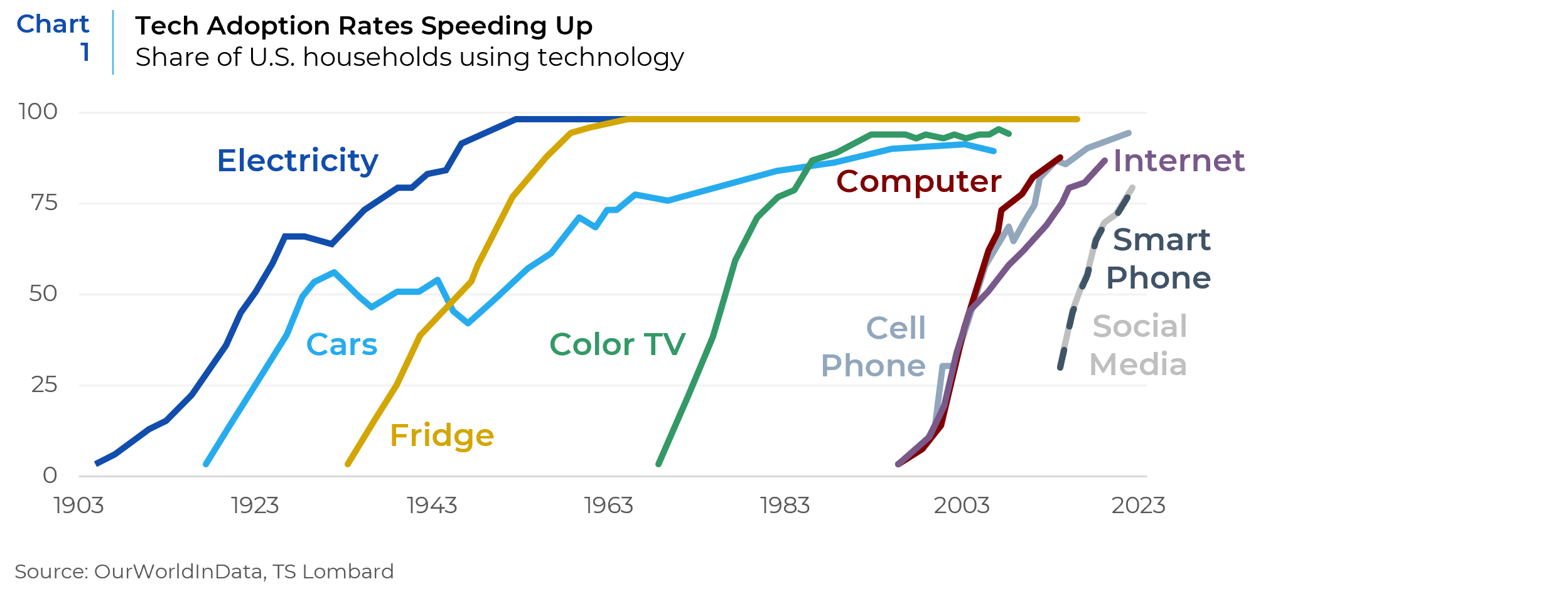

When a product (a technology, a service-style, or some combination of the two) has the right combination of costs, performance, and social acceptance (it is a "whole product") demand for it will increase. Over time, the number of people using the product will increase, following an "adoption curve", wherein a greater and greater share of all of a given market, or all of society, will use the product from a particular provider (e.g., ChatGPT), or from a sector (e.g., smartphones).

Adoption curves have become a particular fascination in our day and age because of how much more quickly it appears our society adopts technologies. It does appear to be getting faster, and in part that may be related to what might be called the flip side of the adoption curve: the experience (or learning) curve.

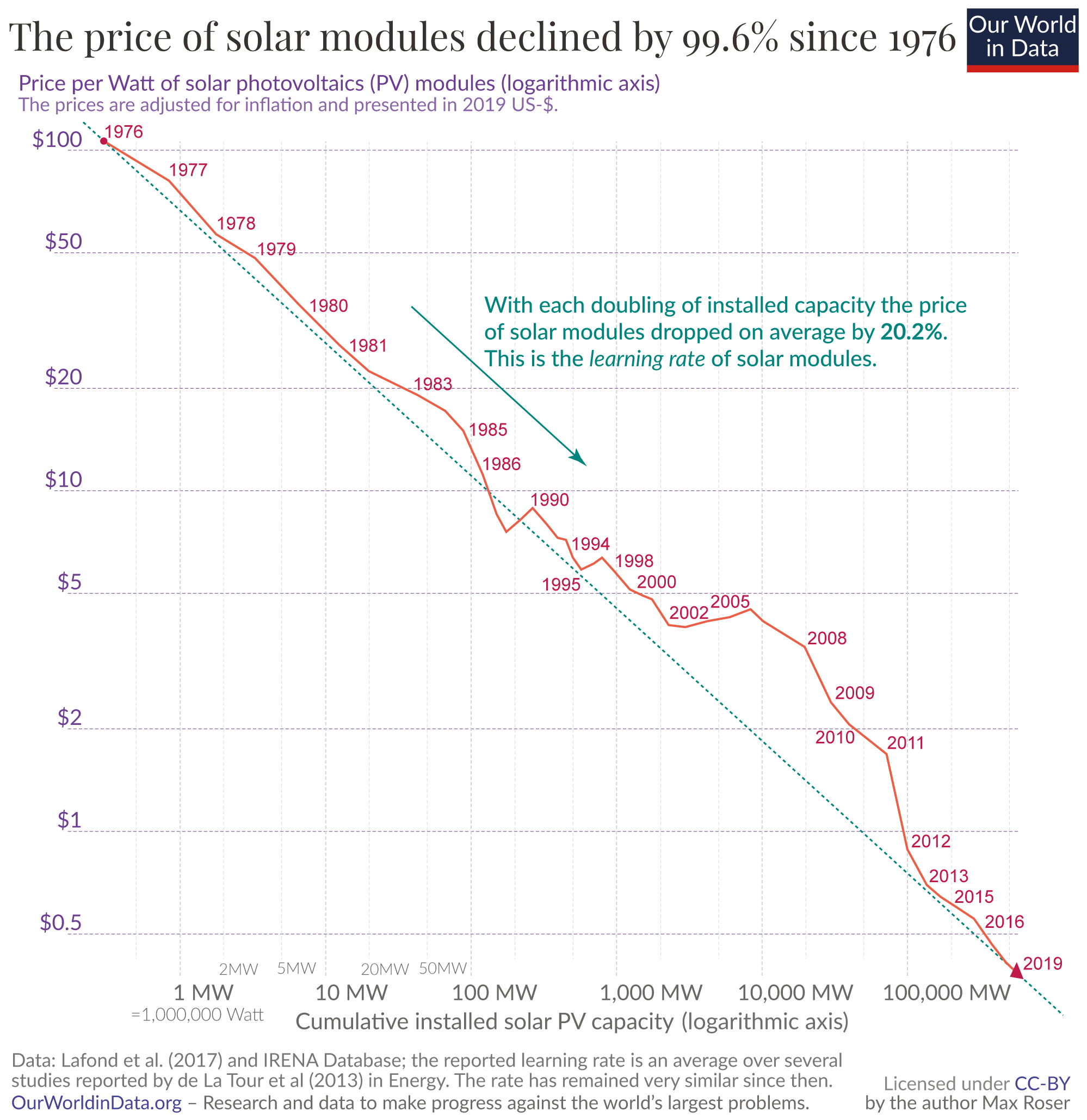

The curve is a way of visualizing the learning rate, which is how quickly the cost of doing something decreases every time we double how much of it we use.

It's extremely important to say: that not all learning curves are created equal. As Michael Liebreich lays out in his brilliant Ezra Lecture on hydrogen, the complexity of a given technology can limit the learning rate and all technologies are inherently dependant on their inputs, like valuable, scarce materials, energy, and trained workers.

From both adoption and learning curves, I think we can learn a central premise that's at the heart of the technology transition:

In order to decrease the cost of a solution we need to buy more of it.

Transitions are, as we have seen, inherently shaped by both our flawed human perceptions of the potential of a given technology or solution. And at the same time, there are some well-studied processes, like the learning curve, that we can leverage to drive positive societal change. This is the intentional aspect of transitions.

American-Italian economist Marianna Mazzucato is probably one of the most well-known thinkers who has helped popularize the idea that all people – through their governments and beyond – can democratically shape where, how, when, and with what, a transition happens.

Mazzucato refers to her approach as a "mission economy," which has gained a lot of attention of late, but is also part of a range of other types of intentional approaches – on the part of governments, industries, communities, and others – to shape a transition and, by extension, an economy. Another, related approach is "industrial policy," and another that's very specific to energy-related issues (in this case, energy efficiency in buildings) is "market transformation."

The common recognition across all of these approaches is that society in general, and government in particular, can not only understand, but also shape many predictable features of major technological and economic transitions (e.g., hype and learning).

As Mazzucato and any other major scholar and practitioner of innovation will tell you, government is a crucial and unavoidable player in all of this. Fundamentally, all of these approaches identify three broad roles for government:

- That government invest, through direct research spending, and incentives (e.g., tax credits), in the creation of both net-new solutions and the iterative betterment of existing ones.

- That government can shape the demand for given solutions by ratcheting up the expectations of the quality and performance of a product through regulations and policies.

- That government can provide direct and indirect support to those who don't compete successfully as technologies and markets change.

One of Canada's great gurus of innovation, Dan Breznitz, has also written about the need for greater government support in shaping the processes of technological innovation and the prosperity that come from them. But part of what Breznitz also says that I think is quite powerful is how the most competitive, equitable, and forward-looking economies draw on intense amounts of collaboration across not only government and business, but also academia, organized labour, community organizations, and others.

The proof, I think, is in the pudding: when you look at the societies, like the Scandinavian countries, Taiwan, Korea, and Singapore, that are extremely wealthy and, at least in broad material terms, equitable, they have high degrees of collaboration across the whole of their society towards clearly-stated and well-understood goals.

For those of us who want our society to improve - to become more efficient with how we use energy and stop warming up the planet in a way that will hurt us - I think it's profoundly grounding to know that we do understand how transitions work and there are tried and truth methods for helping shape that transition democratically.

In contrast to so much of the pessimism I hear about the energy transition in many of my conversations, all of these insights and knowledge should leave us empowered: we have the power to make this transition what we want it to be.

Let's get going.

Sign up for George Patrick Richard Benson

Strategist, writer, and researcher.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.